|

When the Macqueripe beach in Chaguaramas was closed to the public in March because somebody allowed a big hole to form in the seawall and the staircase railings began falling off, everybody got stopped from bathing there, while they fixed it.

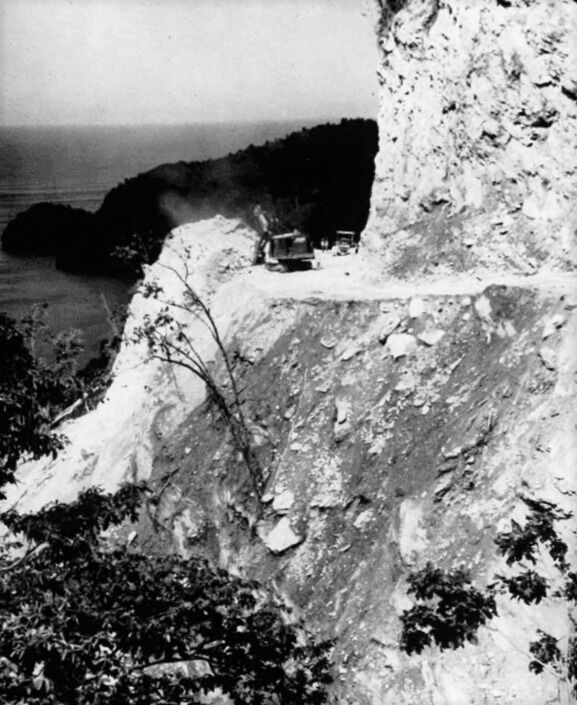

Then no less than a minister of Government reopened the beach months later, only for the health authorities to realise that the Covid-19 virus loves it when plenty people squeeze into a space the size of a football field. So we all got blanked again, with the ban this time extending to bikers, hikers, joggers and those yoga people in the Bamboo Cathedral. Trinis, you might take comfort in knowing that all of this happened before, when Macqueripe was a place you were not allowed. That is, unless you were working for, or had business with, the United States military. In fact, the beach and much of the Chaguaramas peninsula became virtual United States territory during World War II (September 1, 1939-September 2, 1945) when 135,000 American troops were assigned to Latin America and the Caribbean, with the majority of that force coming to Trinidad. The Americans got a 99-year lease to the Chaguaramas area in a deal known as the “Destroyer for Bases” agreement, with the British getting in exchange 50 ageing battleships as they fought the German advance in Europe. The area was acquired under two separate agreements, the first of which, in April 1941, involved 7,940 acres of Crown land, including the five islands in the Gulf of Paria. Land acquisition deal The initial plan was for a naval air station with facilities to support the operation of a patrol squadron of seaplanes and the development of a protected fleet anchorage in the Gulf of Paria as a means of projecting American might, and to protect the vital Panama Canal from a sea attack coming from the south through the Caribbean. Then the Japanese bombed Pearl Harbour, the US declared war on the Axis powers, and Trinidad became of greater strategic importance, accelerating the construction of the Wallerfield and Carlsen Field airbases. And with German submarines prowling the Atlantic and sinking merchant ships in the Caribbean Sea and in T&T’s territorial waters, an airship (blimp) base was developed and coastal defence artillery and bunkers set up around the island. Some of this impressive infrastructure you can still find remnants of in Los Iros, Cedros, St Margaret’s, and Moruga. There are also installations you can still find in Cap-de-Ville where a concrete-fortified administration building became, of all things, the home of the Beast of Biche, Mano Benjamin, after he served his time for his atrocities. To ensure military security of the entire area, a second land acquisition deal was brokered in December 1942, involving 3,800 privately owned acres, with four bays —Carenage, Chaguaramas, Teteron, and Scotland, and two valleys— Chaguaramas and Tucker—becoming areas of separate naval activity. The Seabees The US had been using civilian contractors on the projects pre-war, but when it officially entered World War II, this had to stop. The use of civilians was not permitted since a non-combatant resisting the enemy would be deemed a guerrilla and summarily executed. And this is how the Naval Construction Battalion came to be, units of men capable of fighting and building, and given the phonetic name Seabees. These were men, aged 18 to those in their 60s, who volunteered, and later selected, to help the homeland win the war by building what the military needed. And they came with more than 60 skills—craftsmen, electricians, carpenters, plumbers, equipment operators—capable of building anything alongside the Civil Engineering Corps. More than 325,000 would serve in World War II, in more than 400 locations. Several of these battalions, each comprising about a thousand men, would sail to Trinidad during wartime—the 11th, 30th, 80th, 83rd, and 559th Construction Battalions, and be deployed on every coast of the island (they particularly loved Manzanilla). All of this is mentioned because much of what you see around Macqueripe (the bay was also a US submarine station) was built by the Seabees, with the help of local labour, from the road network and 150-room Tucker Valley naval hospital to the officers’ quarters and beachfront recreational facilities. Macqueripe in the 1940s. Source: U.S. Navy Seabee Museum And because we had to forfeit this area of the peninsula and beach access at Macqueripe when the Americans entered the war, it was agreed that the United States would build and turn over to the colonial government a road to Maracas Bay as compensation. Before then, the only way to get to Trinidad’s iconic beach was by boat or mountain trail. Amazing feat The historians record that work on this seven-and-a-half-mile road was started late in March 1943 by the contractor, continued by the Seabees upon termination of the contract in June and completed and turned over to the local government in April 1944. The records of the 30th Construction Battalion gave an account of the feat thusly: “The road to Scotland Bay was our toughest project. The men had to cut through solid rock most the way and dust and heat did not ease the work. But the road went through and later a complete recreation centre was built at the bay. Our men on the Maracas Road detail did a job there that would have amazed even the most agile of mountain goats, as they manoeuvred around the high rock cliffs and constant landslides.” The road to Maracas, which began at Saddle Road, required the removal of 1,000,000 cubic yards (764,555 cubic metres) of rock and dirt from perilous mountainside heights using dynamite, excavators and bulldozers through virgin jungle. It was described as “24 feet wide, paved with asphalt macadam for a width of 14 feet, and nowhere exceeded a 10 per cent grade, despite its climb from sea level at Port of Spain to a 1,335-foot elevation within a distance of two miles”. The US Navy Construction Battalion bulldozed and blasted a road through the Northern Range to get to Maracas Bay during construction in 1940s. Source: U.S. Navy Seabee Museum There is no record of anyone dying on the project, which we got for free. And it took all of 11 months. Source: [email protected] Daily Express, June 17, 2021

0 Comments

Leave a Reply. |

T&T news blogThe intent of this blog is to bring some news from home and other fun items. If you enjoy what you read, please leave us a comment.. Archives

July 2025

Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed