|

Taken from Angelo Bissessarsingh's archives

This iconic photo shows a scene that was played out countless times under merciless sun in the canefields of Trinidad during the period of indentureship. Here, the labourers squat on a railway line to take a meal. The looming clouds overhead obscure the light, but this break may have been mid-morning, since cane-cutting often began at 4:00 a.m and earlier to avoid the brunt of the sun. They ate from tin carriers which may have held a bit of roti and aloo, talkaree or maybe dal-bhat (dhal and rice) or khora bhat (pumpkin and rice) . There was no shade in the stubbled canefield so the meal had to be taken in the open sun. A drainage canal in front of the lunching group is visible in the photo and one can probably assume that after consuming the meal, these labourers would have bathed their brows and hands in the muddy trench and then returned to work. (Source: Virtual Museum of TT, May 18, 2023) Author : Historian Angelo Bissessarsingh

People erroneously assume that upon expiration of their five year indentureship contracts, coolie labourers from India (1845-1917) were automatically handed five acres of land in lieu of a return passage to India as an incentive to stay in the colony. This is not true. The incentive only existed from 1860 and applied only to those who served a full term of the contract. All incentives ceased in 1880 when it was determined that enough had settled in Trinidad to provide a permanent labour force. The Indian who saved from his pittance and bought out his contract received nothing. He and those before 1860, were left to survive on what little they had saved from their wages ($2.50/month for an adult male, $1.75/month for a female, $0.75 for children up to 12). Neither did the incentive consist of land. It was simply five pounds in cash with which the majority purchased crown lands, which after 1870 were available for one pound per acre. Naturally, there were those who for reasons of profligacy or ill-luck ended up as vagrants on the streets of Port-of-Spain. In 1904, it was estimated that as many 140 Indian vagrants slept in Port-of-Spain, most near Columbus Square. From 1849, an official known as the Protector of the Immigrants was appointed to oversee the general welfare of the immigrants, ensuring that they were treated fairly. Often enough, these bureaucrats were corrupt slackers, who took massive bribes from estate owners to not “rock the boat”. The only one who seems to have been a man of energy and conscience was Charles Melville whose father, Henry Melville (and ironically enough, Protector of the Slaves before emancipation) had been a medical doctor and a man of great reputation in the colony. Charles took a dangerous stance in taking his job seriously and arguing with the all-powerful sugar plantocracy for better rights for the Indians. Since the manager of Usine Ste Madeleine was more powerful than the Governor in those days, Melville soon suffered the fate of the conscientious civil servant and was axed. Melville’s successor was Major Comins (1895-1910), an honest soldier and owner of Glenside Estate in Tunapuna. Comins had been an officer in India and was thought to have been the best fit for the job since he understood “the Indian Problem.” Major Comins travelled extensively across the estates, inspecting barracks, and the dreadful living conditions of the Indians on the plantations. His scathing report published in 1902, and revised in 1908 is an indictment on a labour system that was little better than slavery. He was particularly aggrieved over what he saw at Woodford Lodge Estate where Indians were worked longer than stipulated hours, kept on the estate by armed guards, left untreated at a filthy estate hospital and fed on scanty provisions. It was, however, generally understood that as a planter himself, he sought the colonial interests and moderated his views to such an extent as to be a tool of the establishment and not in favour of those he was supposed to protect. The last Protector of the Immigrants was Arnauld De Boissiere in 1927, a playboy and dandy who only held the office for the 400 pounds a year it paid. In Port-of-Spain, Indian vagrants were a lost people, they could not return to India, and even if they could, they would not have been better off. In Trinidad, they were alien, many spoke little or no English, and were considered less than human, both by the middle and upper class of society, the barrackyard dwellers, and the colonial authorities. Most Indian vagrants survived as porters at sixpence a load. The main employers were marchandes (female vendors of edibles), and laundresses who would engaged porters to carry the bundles of soiled clothing collected from the better homes in Woodbrook and St Clair, returning the freshly ironed and starched pieces, neatly folded on a wooden tray, carried by an itinerant porter. Some fortunate displaced Indians found accommodation at the Ariapita Asylum (known as the Poor House) until that facility was closed in 1929. Largely, most begged charity on the streets until death claimed them, their bodies being consigned to the earth of the Pauper’s cemetery in St James, opened in 1900. In Port-of-Spain, Indian vagrants were a lost people, they could not return to India, and even if they could, they would not have been better off. In Trinidad, they were alien, many spoke little or no English, and were considered less than human, both by the middle and upper class of society, the barrack -yard dwellers, and the colonial authorities. Photo Credit : Adrian Coulling. (Source: Virtual Museum of TT, May 22, 2020) Credit to Author , Angelo Bissessarsingh.

Disclaimer : Article was written by Angelo and in no way intended to offend persons of East Indian descent. Photo credits.. Anthropologists Arthur and Juanita Niehoff. “Cool..e, cool... come for roti, all de roti done.” This was the refrain that haunted many of the formerly indentured Indian immigrants in Trinidad and their descendants from their arrival almost to and including the present day. There is no immigrant story that comes without some painful recollections. It is a testimony however to the spirit of ALL Trinbagonians, that we have managed to grow beyond these recriminations and become a more unified people DESPITE the will of divisive elements such as politicians and pseudo-religious leaders. It seems odd now in a society that counts doubles as a staple food, and where roti has almost epicurean status in some places, that the derision of the Indo-Trinidadians and their food was once commonplace. One of the first articles I wrote for this newspaper back in 2012, was on the roots of Indo-Trinidadian gastronomy which is anchored firmly in the rations which the labourers received during their contracted residences on the sugar plantations of the island. Though the provisions were sometimes augmented or differed according to the estate, the general issue was as Charles Kingsley described it in 1870: “Till the last two years the new comers received their wages entirely in money. But it was found better to give them for the first year (and now for the two first years) part payment in daily rations : a pound of rice, 4 oz. of dholl, a kind of pea, an oz. of coco-nut oil, or ghee, and 2 oz. of sugar to each adult ; and half the same to each child between five and ten years old.” The variations would usually be the addition of a small quantity of saltfish, dried pepper or potatoes. Eked out by provision gardens, often planted with crops brought from India as seeds in the ‘jahaji’ bundles of the labourers, it laid the foundation of a spicy food culture which is as different from anything produced in India today. Those who have dined on authentic Indian dishes will attest to the immense difference from the deliciously creolized creations of Trinidad. Diversification of the Indo-Trinidadian palate came about in the 1880s when many shopkeepers realized what was necessary to attract a clientele from this ethnic group. Wholesalers began to import a variety of spices and curry ground with a ‘sil and loorha’ became more commonplace. Large quantities of ghee, channa (chickpeas). Essentials like mustard oil began to make their appearance at both rural and urban grocers. Nevertheless, Indo-Trinidadian cooking remained an ‘underground’ scene, unknown to most other ethnic groups and rarely tasted outside of the mud huts where it was prepared unless one was invited as a guest. Tempting talkarees, rotis and meetai (sweets) churned out in the aromatic smoke of an earthen chulha (fireplace) were a well-kept secret, not by dint of cultural isolation alone, but also because of a growing sense of shame and self-loathing. Indo-Trinidadian children who attended government schools or schools operated by denominations other than the Canadian Presbyterian Mission to the Indians (CMI) were ridiculed for the lunches they carried, usually sada roti and some sort of bhagi or talkaree. It inculcated a massive inferiority complex which many carried into adulthood. This is well-remembered by persons today and finds its way into Caribbean literature such as the works of Sir V.S Naipaul and Ismith Khan. Well through the 1930s, Indo-Trinidadian concoctions was looked down upon as ‘hog food’ or fit only for the poorest classes. In a calypso sung by the Roaring Lion, he noted the cheapness of the diet by the chorus: “Though depression is in Trinidad, maintaining a wife isn’t very hard, Well you need no ham nor biscuit or bread for there are ways they can be easily fed, like the coolies on bargee, pelauri dhal-bat and dhal-pouri , channa, paratha and the aloo-ke-talkaree” Even doubles at its genesis in the hands of Enamool Deen in Princes Town was viewed as lowly stuff, unfit for consumption by all but rumshop drunks and hungry schoolchildren. In a memoir written by his son, Badru Deen, the struggle to introduce doubles to the urban consumer in San Juan and Port of Spain is well documented. It would be many decades before Trinidad’s most celebrated street food found a place in the national palate. As a fast food, roti was almost non-existent in the towns like Port-of-Spain where it only began to appear in the 1940s during World War II. Roadside roti-stalls were set up with all the necessary utensils, including several coal-pots, churning out dhalpouri with fillings of curried beef (ironic and at once immensely popular), goat, and curried aloo. Chicken a more expensive option. Some rumshops owned by Indians served roti as well. It is a long and stony road that Indo-Trinidadian cuisine has travelled to gain the universal acceptance it enjoys today. (Source: Virtual Museum of TT, May 11, 2023) Sylvia Hunt with a display of jams, jellies and sauces As one of Sylvia Hunt’s eight children, Diana Sambrano learned from an early age how to cook. She and her siblings spent a lot of time helping their famous mother experiment with local fruits and vegetables to concoct delicious meals and snacks, many of which were showcased on her At Home With Sylvia Hunt show on TTT as well as her three cookbooks. Diana and her family have revived some of those recipes for a new generation through Sylvia Hunt’s Cooking: Proud Legacy of our People. The book is a reprint of Sylvia’s first cookbook of the same title published in 1985 and became a vital part of every kitchen in T&T. This version, however, includes additional recipes from the family’s faves such as macaroni pie and poultry stuffing. Recipes were tested and tweaked for the revised edition. It was Sylvia’s wish to have her work continue and Diana asked her son Christopher Sambrano to help fulfill that dream. “I am so happy because I was asking him to try and print it before I pass on. I am proud of him that he is doing it,” she told Loop News during a visit to Trinidad this week. Diana lives in Barbados with her son. The book was published there through Miller Publishing. Writing in the foreword of the 160-page book, Trinidadian writer Patrice Grell-Yursik said the book contains the blueprint for the essential Sunday lunch, from macaroni pie to callaloo to the supreme standard for Trini stewed chicken and pigeon peas. “You’ll find instructions on how to make desserts from the past, like bellyful, haddock, and covity pocham. There are recipes for wild meat agouti casserole anyone? You will discover step-by-step tips for making jams, preserves, pickles and relishes from the shells and peels of local fruits and vegetables, a testimony to the frugality of the era,” Grell-Yursik wrote. The book, said Christopher, is a celebration of our culinary history. “She was really passionate about our indigenous recipes,” he said. “For her, it was about documenting our original recipes which was a big fusion of the European influence, African Influence, and even the Arawak and Caribs and their influence. She did a lot of research and went up and down Trinidad and Tobago documenting these recipes and sharing them with her audiences.” In the introduction to the new cookbook, a reprint from Sylvia’s first cookbook, she recounts the history of many of our indigenous foods and states the need to preserve this information. “Tribute must therefore be made to those persons, many of whom are no longer with us, who have tried to preserve what little is known of the foods of our ancestors and to those who have made a study of them. We are now attempting to build on the past and to create new dishes with what we have, and we are helped by the advances made in science, industry, and commerce,” she wrote. Christopher said for his grandmother, there was also an emphasis on sharing recipes that were relatable and affordable to would allow families to feed themselves on a budget. Who was Sylvia Hunt? Regularly referred to as our local Julia Child, Sylvia Hunt was a pioneer in the food space. Trinidad and Tobago Television (TTT) began operating in 1962 and was the lone television station till 1991. The station became a bastion for local social and cultural shows among them Sylvia’s cooking show which debuted in 1968 and ran until the 80s. Sylvia developed her love for cooking from her parents, Miriam and George Dryce, and her aunt Lydia Gittens. Diana said her mother had the support of her family who also helped to take care of the children due to her busy life. Diana Sambrano and her son Christopher Sambrano In addition to being a cook, Hunt served as an alderman on the Port of Spain city council for two consecutive terms. She also ran a store in downtown Port of Spain called My-Y-Fine Novelty Products which she established in 1947. The store sold dresses, and hats, and doubled as an eatery. Diana recalled working in the store, hemming dresses, covering buttons and buckles, and making handbags among other tasks. She said her mother was insistent that all of her children learn to cook and do handiwork even if they had a profession and she taught them home management skills like making up a bed and how to eat with a knife and fork. Sylvia Hunt making Shaddock candy It was Diana who typed up her mother’s recipes for her column in the Guardian newspaper. Diana worked at the St Vincent Street newspaper for 40 years and also taught sewing at John Donaldson Technical Institute.

Hunt kept busy taking care of her family after her husband fell on hard times but she loved teaching and passing on her knowledge. In addition to her children, she also took in girls from the St Dominic’s Orphanage and taught them many skills including cooking and sewing. She also ran her own private school, the Sylvia Hunt School of Home Economics in St Augustine. “She worked hard,” Diana said, recalling that even after all her children were married, her mother would still cook for them. Sylvia Hunt passed away in 1987. In 1986, she was awarded the Hummingbird Medal, Silver, in recognition of her achievements. (Source: The Loop, May 5, 2023) Sylvia Hunt’s Cooking: Proud Legacy of our People officially launches on May 10. The limited edition book is available at Metropolitan Book Store, The Book Emporium, Paper Based Bookstore and Sylviahuntcooking.com with other leading sellers to follow. . THEY CAME FROM INDIA BRINGING THEIR CULTURAL LEGACY.

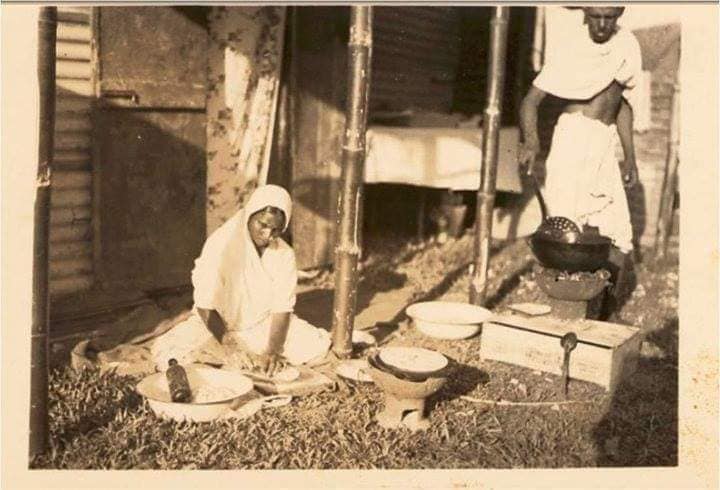

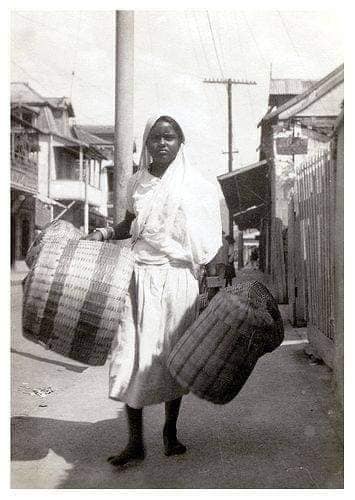

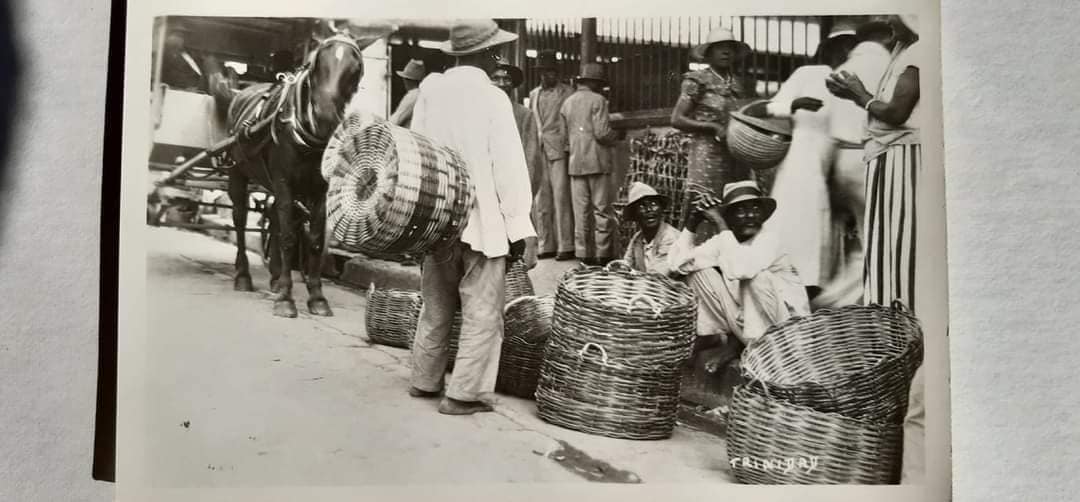

The East Immigrants who were brought from India to Trinidad to work on the sùgar estates possessed a variety of specialized skills which were part of their cultural legacy. Many were artisans and craftsmen and some made a modest living making and selling their handcrafted items. The basket makers were called "tokra-walas " and they were often seen on the streets selling their large baskets that were used for putting items of clothing. Basket weaving was, and still is, an age old tradition still practiced especially be indigenous tribes throughout the world . Long ago when there were no cupboards, plates, or bowls to hold your belongings, baskets served as indispensable items that had multiple purposes. They allowed people to carry water, clothing, food, and much more. Photos courtesy Scott Henderson and Adrian Coulling (2nd photo) (Source: Virtual Museum of T&T, May 3, 2023) |

T&T news blogThe intent of this blog is to bring some news from home and other fun items. If you enjoy what you read, please leave us a comment.. Archives

June 2025

Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed