|

In the first chapter of this three-part series written by historian Angelo Bissessarsingh we are given an insight into the religious awakenings of Hinduism under indentureship among the Indo-Trinidadians of the 19th century.

CHAPTER 1 Hinduism Arrival in the West Indies. Author : Angelo Bissessarsingh. As a historian and erstwhile anthropologist it never ceases to amaze me at how religious and cultural tolerance manifests itself in Trinidad and Tobago. Almost every schoolchild can recite a basic understanding of the annual Hindu festival of Lights, Divali. They know the elements of the triumph of light over darkness, good over evil, bits of the sacred Ramayana and the welcoming of the goddess Lakshmi into the home to ensure a year of prosperity for the family. There are few communities here where in the Hindu calendar month of Kartik (although the earlier month of Ashvin sometimes encompasses the festival) where the firefly lights of tiny clay deyas do not shine forth on the night of the festival, upholding ancient traditions deeply rooted in our ancestry. To fully understand the portent of Divali (Deepaavali as the celebration is known in India) one must take a brief look at the roots of Hinduism in Trinidad and Tobago. In 1845 a group of indentured immigrants arrived from India aboard the Fatel Razack as the first of thousands who would flock hither to found a new society in an alien land. With them to the west came the ancient ways of their motherland and Hinduism had arrived. Initially there was no provision for any cultural or religious freedom since the colonial authorities merely envisioned the presence of the Indians as an easily-replenished source of labour bound to fixed contracts. It was only when the eminent suitability of these people for sugar estate work became apparent then financial and land incentives were offered between 1860 and 1880 which resulted in the formation of a permanent peasant class. It is with this firm establishment that itinerant babajis or pundits began to appear in the villages of their people alongside quaint mandirs with mud walls and carat-thatched roofs. A few of these holy men were real Brahmins but these were in the minority with a large number merely being elevated to piety by having a considerable knowledge of the epics of the Ramayana and Mahabharata. Although most of the indentured immigrants were from agrarian classes were from rural stock and formerly bound by the fetters of the caste system, it was noted in 1887 by J.H Collens (in a rather myopic account) that a widespread knowledge of the epics was apparent and this of course was the local origin of the Ramayana readings and Ramleela plays which have characterized Indo -Trinidadian Hinduism ever since: “It must be acknowledged that the Puranas are a mass of contradiction, extravagance, and idolatry, though couched in highly poetical language. It is, nevertheless, astonishing how familiar the Trinidadian coolies are with them ; even amongst the humble labourers who till our fields there is a considerable knowledge of them, and you may often in the evening, work being done, see and hear a group of coolies crouching down in a semicircle, chanting whole stanzas of the epic poems, Ramayan etc. In the preface of the Ramayan it is stated that he who constantly hears and sings this poem will obtain the highest bliss hereafter, and become as one of the gods.” It is this spiritual awakening which inevitably led to the introduction of Divali and other Hindu festivals to Trinidad. In the next chapter of this series, we will look at how deyas punctuated the darkness in rural Trinidad as Divali emerged as a national phenomenon. Photo :Three babas or pundits in Trinidad circa 1894. The permanent settlement of formerly indentured immigrants paved the way for a cultural and religious expansion of their identities hitherto suppressed by the colonial plantocracy. (Source: Virtual Museum of T&T, Oct 25, 2024)

0 Comments

MEMBERS of the Surinamese First Peoples participate in the Water Ritual, part of Heritage Week activities hosted by the Santa Rosa First Peoples Community at the Arima River, Blanchisseuse Road on October 12.

The Santa Rosa First Peoples community held its annual Water Ritual at the river, celebrating their cultural heritage and spiritual connections. The ritual brought together members from various tribes, including the Trio Tribe from Suriname, who adorned themselves in traditional costumes and sacred body paint. According to Ricardo Bharath Hernandez, Santa Rosa First Peoples’ chief, the tribal garments are crucial for honouring the spirits and ancestors, allowing participants to seek direct messages through their connection with nature. The ceremony featured offerings made to the water, emphasising the community's deep respect for the environment and its role in their spiritual practices. Elders and leaders of the various tribes, including Bharath Hernandez, played pivotal roles in guiding the rituals, ensuring sacred traditions were upheld, and fostering a sense of unity and reverence among participants. The event not only highlighted the community's rich cultural heritage but also reinforced their ongoing with the spiritual world. The Water Ritual is part of the Santa Rosa First Peoples Community Heritage Week celebrations from October 12-18. Other events include a film screening at the Arima mayor’s temporary office on October 15, a ceremony remembering the ancestors at the Red House in Port of Spain on October 16, and a cultural and social mixer at the Heritage Village, Arima, on October 18. (Source: Newsday, October 15, 2024) In the garden at the side of the front waiting room of the Office of the President of Trinidad and Tobago is a tiny grave marker marking the spot where Digger was buried .

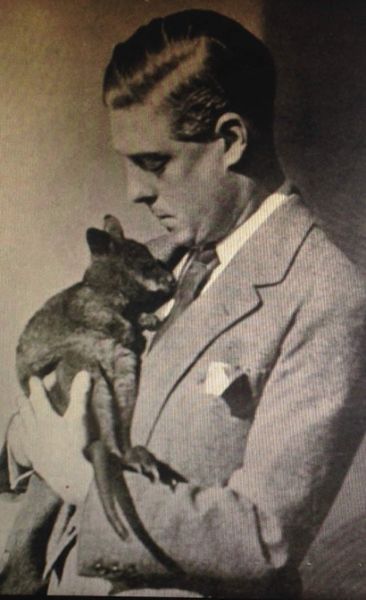

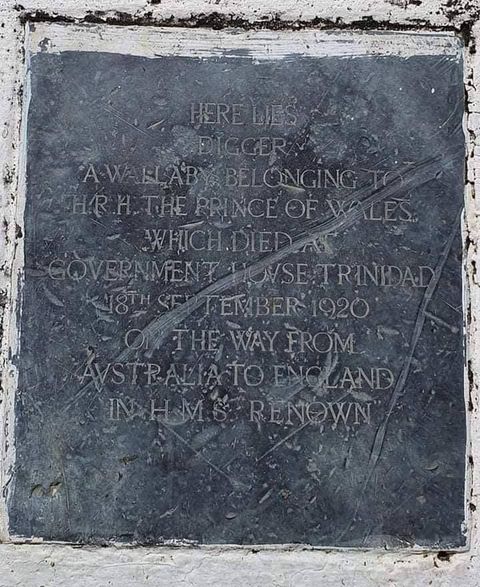

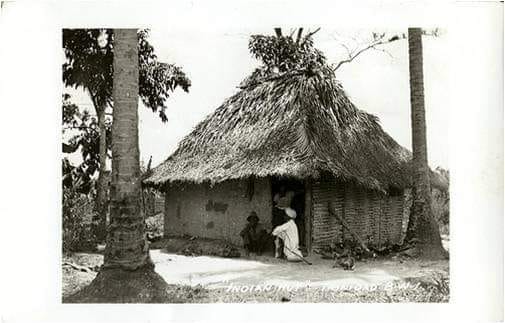

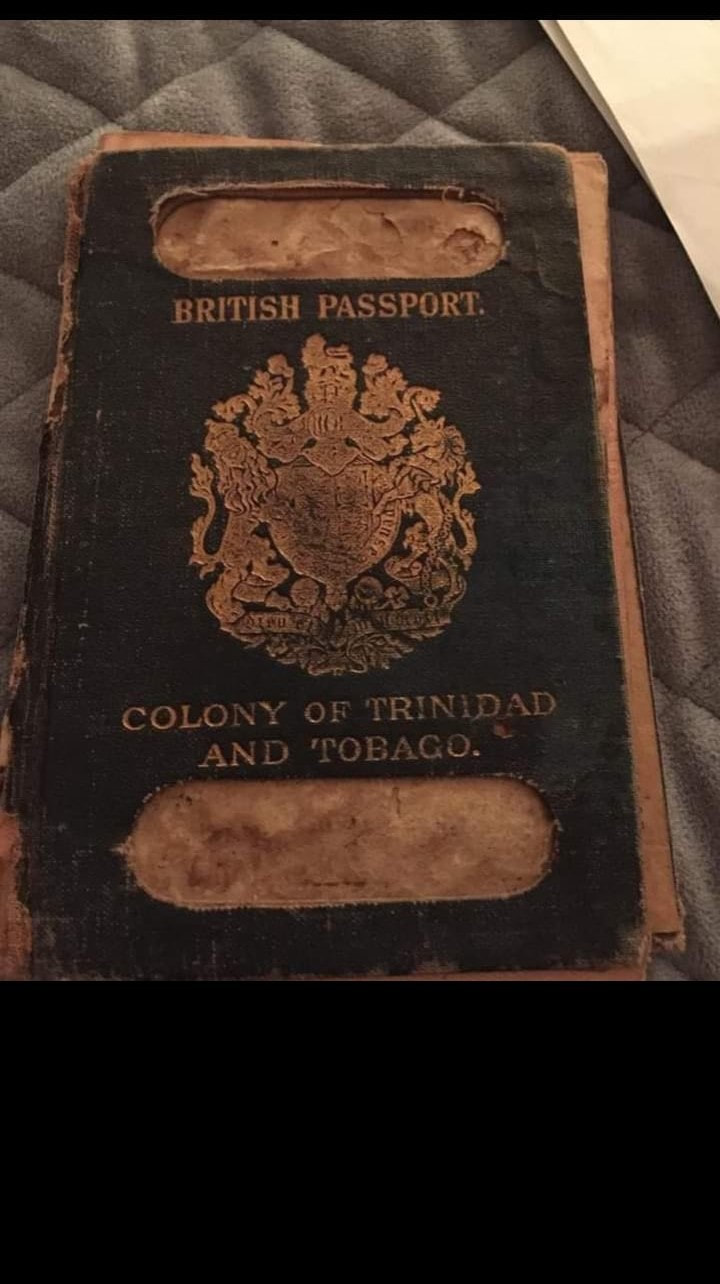

So who or what was Digger? You may be in for a surprise when you read the Story of Digger who was buried at the side of the front waiting room at the Office of the President. THE STORY OF DIGGER Digger was a Wallaby brought by Edward Prince of Wales in 1920 who was returning home after a world tour. Edward was the eldest child of King George V and himself became King in 1936 until his abdication later that year to marry Wallis Simpson. Edward had served in WWI and was awarded the Military Cross in 1916. During his visit to Australia, crowds regularly shouted 'digger' throughout his visit. Digger is Australian slang for an Australian soldier. He became known there as the 'Digger Prince'. According to their military museum, 'digger prince' would have been one of the highest compliments at the time given the regard in which all servicemen and women were held. Edward visited Australia right before Trinidad (April 1920) and received a wallaby given to him by an Australian girl ,among other animals including a cockatoo, emu chicks and parrots. The Prince of Wales's wallaby, had become the greatest of all the many pets on board the ship . Less than two feet high, in form like a wee kangaroo, he was entirely fearless and always full of life. He had become the soul of the after-cabin during the homeward voyage. On the homeward bound journey , the Prince and his entourage stopped in Trinidad for a courtesy visit . During their visit to Trinidad Government House in Port of Spain, Digger was let loose in the garden for some exercise and fresh air . Unfortunately in a tragic moment, Digger ate some poisonous plant or flower in the grounds of Government House. Brandy, castor oil were administered and the most devoted care was given but to no avail . Unfortunately, "Digger" died that evening, mourned most bitterly by the Prince and all his Staff. He is buried in the Government House Garden at Trinidad, and none of his friends will ever pass that way without a pilgrimage to his tiny memorial stone. The inscription on the tomb reads: HERE LIES DIGGER A WALABY BELONGING TO H.R.H. THE PRINCE OF WALES WHICH DIED AT GOVERNMENT HOUSE TRINIDAD 18TH SEPTEMBER 1920 ON THE WAY FROM AUSTRALIA TO ENGLAND IN H.M.S RENOWN Due credit to following sources : Geoffrey Mac Lean Snapshot of the History of Trinidad and Tobago by Angelo Bissessarsingh Photo credit : (Prince Edward and Digger) , Geoffrey Mac Lea (Source: Angelo Bissessarsingh Virtual Museum of Trinidad and Tobago, Sept 28, 2024) Well according to late Historian Angelo Bissessarsingh, the first emergence of the name GOLCONDA in the annals of Trinidad local history actually predate the arrival of East Indians to the colony by at least six years. The Government Blue Book for 1839 reveals that George Monkhouse, proprietor of Golconda Estate paid the sum of found pounds , three shillings on his property. Though the mist of times have shrouded all details it is assumed that Lt. Monkhouse christened his Trinidad holding in memory of his time spent in Golconda, India where he served as an officer with the East Indian Regiment. Outside the great Historical City of Hyderabad, India , perched squarely on the Deccan Plateau , stands the ruins of the once mighty fortress known as GOLCONDA. Its name in native Telugu language literally translates “ round hill”. Historically, the Golconda region was renowned for its diamonds, derived from the conglomerate rocks of the nearby hills, including the world-famous Koh-i-noor diamond . The Trinidad GOLCONDA located in the region of Penal/Debe like its namesake also occupies the top of a round hill. Stay posted to read other significant events in Golconda's history. Photo : " A hut in Golconda c. 1905" (Source: Angelo Bissessarsingh Virtual Museum of Trinidad and Tobago, Sept 29, 2024) Source : Angelo Bossessarsingh's 2010 historical archives.

I cannot take credit for this discovery. Chrissy and Lincoln Chinsammy, two surprisingly young people and their family of La Romaine deserve many praises for their consciousness in preserving a seemingly morbid, yet vital relic of our history. My research shows that the uninscribed tomb belongs to Mary Haynes , wife of Charles Haynes (Manager of Bien Venue Estate) and the youngest daughter of Henry Brown Esq. , a merchant of Grenada. She died in childbirth in 1871 which was a fairly common occurrence and was buried on the plantation. For many years, I have known that a tomb for Mary Haynes existed somewhere on the old estate, which has become heavily populated and developed over the years. On Friday, Chrissy told me about this grave very near to her family’s home on lands which once formed part of Bien Venue. She said that the lands had been sold to a developer who had committed under pressure to preserve the tomb intact instead of doing the Trini ting and bulldozing it. Such was the sensitivity of the Chinsammys, that when the limestone of which the tomb is composed began to dissolve and crumble, they began an annual ritual of plastering it with cement. The grave is on a gentle slope overlooking a pasture which has become the village sports ground. On the ridge opposite the grave is the old Manager’s residence which stands on the same site as the house Mary and Charles would have lived in. The royal palms line the old Concord road which was the main road for the estates of South Naparima in the 19th century. Interestingly, the indentured immigrant cemetery for the old estate is a long distance away across a valley. Mary and her unborn child were interred alone. The tomb may be seen on Boodhai Tr. Off La Fortune Rd., La Romain.  Ray Funk MANY Trinidadians have risked their lives in service of others. Some have been memorialised; others are little known. One who is not well known is Dr Arnold Donawa, a dental surgeon and outspoken advocate for the rights of Africans, African Americans, and working people. Not just an advocate, he risked hs life during the Spanish Civil War for his heartfelt beliefs in a life of commitment and service. Born in Trinidad in 1899, he went to the US in 1916 to study dentistry. He got a first degree at Howard University in 1922, interned in Boston, then worked at the Forsythe Harvard research lab and went on to get an advanced degree at the Royal College of Dental Surgeons in Toronto. He was a radiological instructor, then did postgraduate work in pathology, preventive dentistry and periodontia. He opened a practice in Harlem and became president of the Harlem Dental Association. In 1925, he published an article on root-canal procedures in the first issue of the journal American Dental Surgeon. He was appointed dean of the College of Dentistry at Howard University in 1929, but resigned in an internal administrative struggle. He later sued Howard and was vindicated with a monetary award for lost wages. Donawa returned to Harlem and private practice as a dentist and oral surgeon, and was soon deeply engaged in civil-rights issues. He developed a robust anti-fascist voice in the Daily Worker at that time. In the summer of 1935, in response to actions by Mussolini in invading Ethiopia and wrote, “We must create unity between the Italian and the Negro people…We must arouse sentiment to help Ethiopia.” He became one of the leaders of the Medical Committee for the Defense of Ethiopia and in November he reported to the New York Age that two tons of medical supplies had been gathered, sent, and had reached the forces fighting in Ethiopia. When Mayor LaGuardia participated in a pro-Italy rally, he wrote to him, “As the mayor of the largest city in the US, which has declared itself completely neutral, your action on behalf of Italy cannot be construed as a private affair; and the Medical Committee for Defense of Ethiopia voices not only its own protest but the justified indignation of the Negro masses of Harlem and other sections of New York City.” In 1936, at the start of the Spanish Civil War, he was again fighting fascism, this time against Franco. But instead of offering support only from a distance, he volunteered and went to the front lines in Spain for over a year. His help was welcomed, and he became the head of oral surgery at the American Base Hospital at Villa Paz. Early in his time in Spain, he suffered a minor injury in an aerial assault in the town of Port Bau. A reporter from the Daily Worker was there. “The bombers had just been over and Dr Donawa was flung to the ground. When the planes passed on, he rose, and continued talking where he left off, without looking up. Always cool, brilliant at his task, he now directs the work of a large base hospital.” The reporter called him, “a sculptor in bone and flesh who brought men back to life and health.” Poet Langston Hughes visited Donawa during his stay in Spain. In his memoir I Wonder as I Wander, Hughes wrote that Donawa “was in charge of rebuilding the faces of soldiers there whose jaws were splintered, teeth shattered or chins blown away. This tall, kindly…man, a favorite with the patients, stayed in Spain until near the end of the war and brought back with him a group of wounded Americans.” The New York Post reported he brought back 60 wounded volunteers and six nurses. Donawa was interviewed by the Daily Worker on his return after a year and a half of service, and talked about the importance of such missions: “I think the Negro people have a special interest in preserving democracy because we know full well that what rights we have depend upon the existence of a democratic government. These rights can be extended only by the growth of democracy. If we fight for Spain, or any other country whose democracy is at stake, we are fighting for ourselves.” When the Japanese bombed Pearl Harbor, Hawaii, in 1941 – the outrage that drew the previously neutral US into World War II – Donawa was the executive secretary of the newly formed Negro Committee for American-Allied Victory, which proclaimed, “America must remove the shackles from its Negro citizens and tear down Jim Crow barriers now standing in the way of full participation in the war effort.” Later in life, he continued to be an activist. In 1945, he was elected president of the North Harlem Dental Association and advocated for socialised medicine that would “guarantee medical protection for all Americans.” The next year, as head of the Manhattan Dental Association, he was a signatory on a telegram to President Truman about anti-labour legislation. “We, and the Negro people of Harlem for whom we speak, are vigorously opposed to the drastic curbs you have asked Congress to clamp down on the organised workers of our country. To deprive workers of the right to strike is to destroy their final weapon of defense against oppressive employers. “To force involuntary servitude upon workers is to adopt the fascist pattern of slave labor. The Negro people have learned that a strong and democratic labor movement is our best guarantee of security and progress. We will defend labor's rights as our own.” It is unclear what consequences Donawa faced over the years for being so outspoken. During the 1950s, McCarthy anti-communist crusade, his name appears on lists of those under investigation, but it is unknown what action, if any, was taken against him. He later retired from his practice and reportedly returned to Trinidad and died in the 1960s, but details are lacking. What is clear is that he was an outspoken advocate for civic rights at a time when few were willing to speak out, and fewer still to risk their lives to help the injured, during a war almost a century ago. (Source: Newsday, August 11, 2024) What's the Hindustani name for these bracelets?

This priceless family heirloom was shown to us by my sister's friends when we visited their home. The pair of bracelets were an inheritance from the gentleman's great grandmother who was of East Indian descent , her parents having come from India. My sister Ann begged to hold these historical artifacts in her hands just for a moment. Let's see which members can identify this piece of jewelry and the part of the body it was worn. According to my sister they were quite heavy . Pity that these family heirlooms can no longer be kept by family members but have to be hidden away in safety deposit boxes in a bank maybe to be taken out by another generation to follow. An eyewitness account of the 1937 Labour Riots in Trinidad.

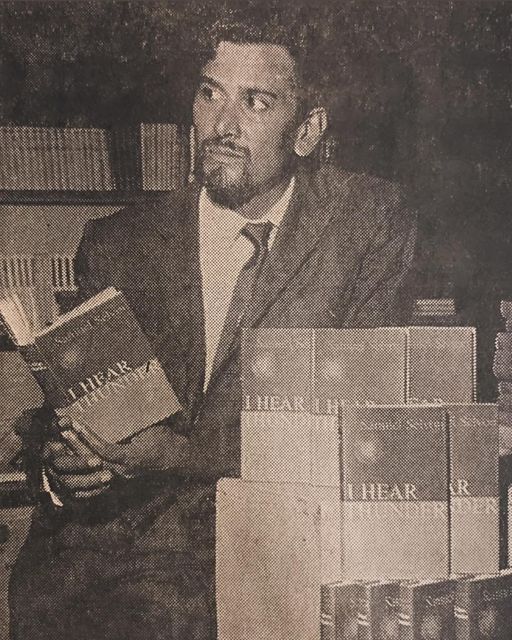

I remember it like it was yesterday. The air was thick with the smell of burning petrol, the cries of anger, and the promise of change. I was twenty-five years old, a young man working the oil fields in Fyzabad. The discontent that had been simmering for years finally erupted into the madness of 1937. The oil fields were our lifeblood and our chains. For generations, men like me toiled under the relentless sun, drilling for black gold that enriched foreign hands while we lived in squalor. Our lives were a cycle of labour and poverty, with no end in sight. The colonial masters and local overseers held all the power, and we had none. But something was changing. The whispers of discontent grew louder, and the spark was lit by one man—Tubal Uriah "Buzz" Butler. Butler was a man of fire and brimstone, his speeches ignited the hope that had long been dormant in our hearts. He spoke of justice, of fair wages, of a future where our children would not be bound by the same chains. On June 19th, a gathering was called in Fyzabad. Hundreds of us, workers from all over Trinidad, assembled to hear Butler speak. The air was electric with anticipation. As Butler's voice rang out, calling for a strike, a unified cry of agreement rose from the crowd. It was the first time I felt the true power of solidarity. But the colonial authorities were not blind to our gathering storm. They saw Butler as a threat, a trigger that could ignite a full-blown rebellion. As we marched through the streets, demanding our rights, the police confronted us, their guns and batons raised. The clash was inevitable. I remember the chaos, the sounds of struggle, and the first shot fired. It was like a dam had burst. I saw friends fall, blood staining the earth, but I also saw courage. Men and women who had been beaten down for so long stood tall and fought back. We were no longer silent; our voices rose in unison against the oppression. In the midst of the riot, I found myself alongside Elma Francois, a woman whose passion for justice matched Butler's. Her presence was a beacon, her words a rallying cry. "We fight for our future!" she shouted, her voice cutting through the noise. Inspired, I fought harder, my anger transforming into a determined force. The days that followed were a blur of strikes, protests, and clashes with the authorities. The news of our struggle spread like wildfire across Trinidad, and soon, the entire island was gripped by the spirit of resistance. The colonial government, faced with unprecedented unrest, had no choice but to negotiate. It wasn't an easy victory, and it didn't come without a cost. Lives were lost, and even more were injured. Butler and Francois faced imprisonment, but their sacrifice was not in vain. The riots led to significant changes in labour laws and the formation of trade unions, giving workers like me a voice we had long been denied. Now, as I look back on that time period, I feel a mix of pride and sorrow. Pride for what we achieved, and sorrow for those who didn't live to see the fruits of our struggle. Labour Day in Trinidad is more than a public holiday; it's a reminder of our resilience, our unity, and the enduring spirit of the people. Every year, when June 19th comes around, I tell my grandchildren the story of the Labour Riots. I want them to know that the rights we enjoy today were not given, but earned through sweat, blood, and unwavering determination. The flame of 1937 still burns within me, and it is my sincere hope that it kindles one within you. An excerpt from the personal collection of Joseph Crawford (1987) (Source: Sanfernando Community North Library, June 19, 2024) One of the best known names in Caribbean literature, Sam Selvon, was born on May 20th in 1923!

As an author, Selvon is celebrated for his vivid depictions of Caribbean life and stories of West Indian migration. Many of his later writings drew from his experiences as a member of the Windrush generation of Caribbean immigrants to Britain in the 1950s. His book, “The Lonely Londoners” (1956) is still recognized as one of the first novels to incorporate Caribbean dialects in its telling of working-class migrant life in the UK. Over the years, Selvon authored a number of books, including “Ways of Sunlight” (1957), “Those Who Eat the Cascadura” (1972) and “Moses Ascending” (1975). In 1976, he co-wrote the screenplay for British film “Pressure” with Horace Ové, celebrated as the UK's first Black dramatic feature-length film. He was a two-time winner of the prestigious Guggenheim Fellowship, a recipient of the Hummingbird Medal (Gold, 1969) and the Chaconia Medal (posthumously, 1994). In the 1980s, Selvon was honoured with degrees from the University of the West Indies (1985) and Warwick University (1989). Born in San Fernando, Selvon attended Naparima College before serving 5 years in the West Indian Royal Navy (R.N.V.R) during WWII, on ships in the Caribbean. After the War, Selvon worked as a reporter at the Trinidad Guardian Newspaper (1945-1950). He also wrote stories under pseudonyms and had some of his work broadcast by the BBC. Encouraged by this success, he migrated to the UK in 1950 with the manuscript of his first book “A Brighter Sun” (1952). In London, Selvon worked several jobs, while his short stories were published by various British magazines. He also produced two television scripts for the BBC: “Anansi the Spider Man” and “Home Sweet India.” Selvon later moved to Canada, where he became a fellow at the University of Dundee, and a professor in creative writing at the University of Victoria. He passed away on April 16th 1994 in Trinidad. In 2018, on what would have been his 95th birthday, Selvon was honoured by Google with a “Google Doodle”. This photo is courtesy of the Sunday Guardian newspaper, May 5th 1963, and is part of the National Archives of Trinidad and Tobago Newspaper Collection. (Source: National Archives of T&T, May 20, 2024) |

T&T news blogThe intent of this blog is to bring some news from home and other fun items. If you enjoy what you read, please leave us a comment.. Archives

November 2024

Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed