|

An interesting article http://www.newsamericasnow.com/10-black-caribbean-born-executives-in-top-u-s-posts/ Facebook Global Director of Diversity Maxine Williams (L), was born in Trinidad. (Photo Credit: Robert A Tobiansky)

0 Comments

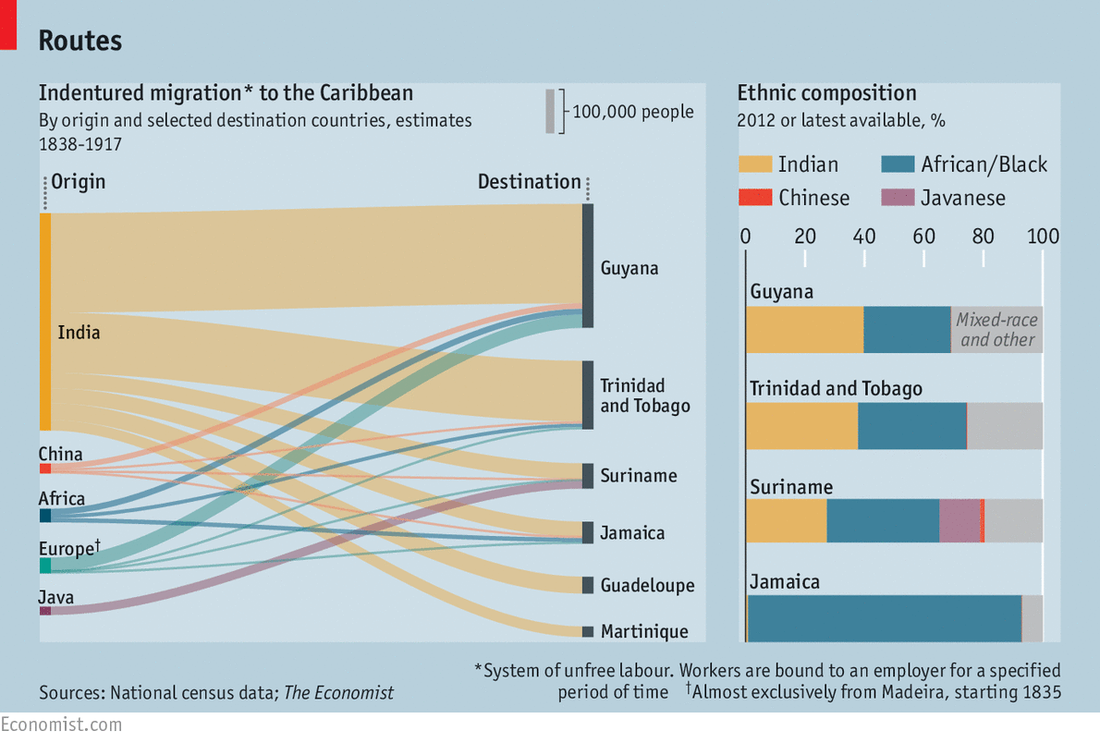

When Anthony Carmona, the president of Trinidad and Tobago, showed up in a Carnival parade last month wearing a head cloth, white shorts and beads like those worn by Hindu pandits, he was not expecting trouble. Nothing seems more Trinidadian than a mixed-race president joining a festival that has African and European roots. But some Hindus were outraged. “[O]ur dress code has never been associated with this foolish and self-degrading season,” huffed a priest. Trinidad’s cultures blend easily most of the time; occasionally, they strike sparks. The Hindu-bead controversy is not the only one ruffling feelings among Indo-Trinidadians. Another is caused by a proposal in parliament to raise the minimum age for marriage to 18 for all citizens. Currently, Muslim girls can marry at 12, girls of other faiths at 14. Muslim and Hindu traditionalists want to keep it that way. Another argument has been provoked by the disproportionate number of Trinidadians who have joined Islamic State (IS). About 130 of the country’s 1.3m people are thought to have fought for the “caliphate” or accompanied people who have. That is a bigger share of the population than in any country outside the Middle East. The government wants a new law to crack down on home-grown jihadists, which some Muslim groups denounce as discriminatory. The attorney-general, Faris Al-Rawi, is guiding both measures through the legislature. Both debates are causing unease in the communities that trace their origins to the influx of indentured workers in the 19th century. This month marks the 100th anniversary of the end of that flow. By bringing in large numbers of Indians, mostly Hindus and Muslims, the migration did much to shape the character of the Caribbean today (see chart). The arguments about marriage and terrorism are part of its legacy. The migration from India began in 1838 as a way of replacing slavery, banned by Britain’s parliament five years earlier. Recruiters based in Calcutta trawled impoverished villages for workers willing to sign up for at least five years of labour—and usually ten—on plantations growing sugar, coconut and other crops in Trinidad, British Guiana (now Guyana), the Dutch colony of Suriname and elsewhere.

Workers were housed in fetid “coolie” barracks, many of which had served as slave quarters, and were paid a pittance of 25 cents a day, from which the cost of rations was deducted. Diseases like hookworm, caused by an intestinal parasite, were common. But the labourers’ lot was better than that of enslaved Africans. Colonial governments in India and the Caribbean tried to prevent the worst abuses. Workers received some medical care and were not subject to the harsh punishments meted out to slaves, notes Radica Mahase, a historian. In some periods the colonial government offered workers inducements to stay at the end of a contract: five acres of land or five pounds in cash. Opposition from Indian nationalists and shortages of shipping during the first world war prompted the British government of India to shut down the traffic on March 12th 1917. By then, more than half a million people had come to the Caribbean. Today, just over a third of Trinidad and Tobago’s people say they are of Indian origin, slightly more than the number of Afro-Trinidadians; the share is higher in Guyana, lower in Suriname. Hindus outnumber Muslims. Many, especially those whose forebears were educated at Presbyterian schools, are Christians. Caribbean people of Indian origin are as successful and well-integrated as any social group. Many of Trinidad and Tobago’s state schools have religious affiliations but are ethnically mixed; the government pays most of their costs regardless of denomination. Eid al-Fitr, which celebrates the end of Ramadan, and Diwali are public holidays. Many Hindus celebrate the religious festival of Shivaratri, then join in Carnival parades. “An individual can have multiple identities,” says Ms Mahase. Politics still has ethnic contours. In Trinidad and Tobago, most voters of African origin support the People’s National Movement, which is now in power. Indo-Trinidadians tend to back the opposition United National Congress. Guyana’s president, David Granger, is from a predominantly Afro-Guyanese party. But these distinctions are blurring. A growing number of Caribbean people identify with neither group. Nearly 40% of teenagers in Trinidad and a quarter in Guyana call themselves mixed-race or “other”, or do not state their ethnicity in census surveys. When both countries hold elections in 2020, these young people are likely to vote less tribally than their parents do. Trinidad’s jihadist problem is in part caused by the choice of new identities rather than by the embrace of established ones. Many of IS’s recruits are Afro-Trinidadian converts to Islam. Mr Al-Rawi, who is leading the fight to stop them, claims descent from the Prophet Muhammad through his Iraqi father, but has a more relaxed view of religion. His mother is Presbyterian, his wife is a Catholic of Syrian origin and one of his grandfathers was a Hindu. The anti-terrorist and child-marriage laws he is promoting, though seemingly unrelated, are rebukes to rigid forms of identity. The anti-terrorist law would make it a criminal offence within Trinidad to join or finance a terrorist organisation or commit a terrorist act overseas. People travelling to designated areas, such as Raqqa in Syria, would have to inform security agencies before they go and when they come back. Imtiaz Mohammed of the Islamic Missionaries Guild denounces the proposed law as “draconian”. The proposal to end child marriage affects few families; just 3,500 adolescents married between 1996 and 2016, about 2% of all marriages. But it has been just as contentious as the anti-terrorism law. The winning calypso at this year’s Carnival, performed by Hollis “Chalkdust” Liverpool, a former teacher, was called “Learn from Arithmetic”. Its refrain, “75 can’t go into 14”, mocked Hindu marriage customs and implicitly backed the legislation to raise the marriage age. Satnarayan Maharaj, an 85-year-old Hindu leader, called it an insult. The government has enough votes in parliament to pass the law in its current form, but opponents may challenge it in the courts. Traditionalists may thus hold on to an anachronism imported from India, at least for a while. The bead-wearing, calypso-dancing president is probably a better guide to what the future holds. Source: The Economist, Mar 11, 2017  That the limbo originated as an event that took place at wakes in Trinidad and Tobago? Here is a glimpse of its origins: Time Frame

LIFE AFTER INDENTURESHIP - Article written by ANGELO BISSESSARSINGH (Taken from his manuscripts)3/24/2017  People erroneously assume that upon expiration of their 5 year indentureship contracts, coolie labour from India (1845-1917) was automatically handed five acres of land in lieu of a return passage to India as an incentive to stay in the colony. This is not true. The incentive only existed from 1860 and applied only to those who served a full term of the contract. All incentives ceased in 1880 when it was determined that enough had settled in Trinidad to provide a permanent labour force. The Indian who saved from his pittance and bought out his contract received nothing. He and those before 1860, were left to survive on what little they had saved from their wages ($2.50/month for an adult male, $1.75/month for a female, $0.75 for children up to 12). . Neither did the incentive consist of land. It was simply five pounds in cash with which the majority purchased crown lands, which after 1870 were available for one pound per acre. Naturally, there were those who for reasons of profligacy or ill-luck ended up as vagrants on the streets of POS. In 1904, it was estimated that as many 140 Indian vagrants slept in POS, most near Columbus Square. From 1849, an official known as the Protector of the Immigrants was appointed to oversee the general welfare of the immigrants, ensuring that they were treated fairly. Often enough, these bureaucrats were corrupt slackers, who took massive bribes from estate owners to not 'rock the boat'. The only one who seems to have been a man of energy and conscience, was Charles Melville whose father, Henry Melville (and ironically enough, Protector of the Slaves before emancipation) had been a medical doctor and a man of great reputation in the colony. Charles took a dangerous stance in taking his job seriously and arguing with the all-powerful sugar plantocracy for better rights for the Indians. Since the manager of Usine Ste. Madeline was more powerful than the Governor in those days, Melville soon suffered the fate of the conscientious civil servant and was axed. Melville’s successor was Major Comins (1895-1910) , an honest soldier and owner of Glenside Estate in Tunapuna. Comins had been an officer in India and was thought to have been the best fit for the job since he understood “the Indian Problem”/ Major Comins travelled extensively across the estates, inspecting barracks, and the dreadful living conditions of the Indians on the plantations. His scathing report published in 1902, and revised in 1908 is an indictment on a labour system that was little better than slavery. He was particularly aggrieved over what he saw at Woodford Lodge Estate where Indians were worked longer than stipulated hours, kept on the estate by armed guards, left untreated at a filthy estate hospital. and fed on scanty provisions . It was however generally understood that as a planter himself, he sought the colonial interests and moderated his views to such an extent as to be a tool of the establishment and not in favour of those he was supposed to protect. The last Protector of the Immigrants was Arnauld De Boissiere in 1927...a playboy and dandy who only held the office for the 400 pounds a year it paid. POS Indian vagrants were a lost people....they could not return to India, and even if they could , they would not have been better off. In Trinidad, they were alien, many spoke little or no English, and were considered less than human, both by the middle and upper class of society, the barrackyard dwellers, and the colonial authorities. Most Indian vagrants survived as porters at sixpence a load. The main employers were marchandes (female vendors of edibles), and laundresses who would engage porters to carry the bundles of soiled clothing collected from the better homes in Woodbrook and St. Clair , returning the freshly ironed and starched pieces , neatly folded on a wooden tray, carried by an itinerant porter. Some fortunate displaced Indians found accommodation at the Ariapita Asylum (known as the Poor House) until that facility was closed in 1929. Largely, most begged charity on the streets until death claimed them, their bodies being consigned to the earth of the Pauper's cemetery in St. James, opened in 1900.  As the country remembers the 100th anniversary of the the end of Indian Indentureship, here is a tradition from India that at least one family still maintains. Sunildath Ramlakhan and his relatives still practice the the art of leepaying. To leepay is to use a mixture of cow dung (gobar), dirt and water. To which will be spread across part of a house. This was something the immigrant Indian did at their mud and thatch homes. The only difference was the forefathers would paste the entire house with gobar which acted as a barrier. When the Express visited Ramlakhan's residence in Quinam Road, Penal, we were treated to how the materials were prepared and used to leepay. Despite the strong and fresh scent of cow manure, Ramlakhan's sister-in demonstrated what the process was about. In separate old buckets were the gobar and dirt mixture and water in another. She removed the old grass and broke up the gobar and dirt until it had a fine consistency. She said the manure was procured by visiting several areas where people were rearing cattle. Only freshly dropped cow dung would be used to make the paste. Ragoonanan spoke of the medical benefits of using the mixture can have once its spread. “Children don't get sick when they are walking on it. The ground is always cool,” she said. Next, Ragoonanan knelt down on the floor and using an old cloth, she dipped it into the mixture. She would then, transfer the paste to the floor and from one area to another in a sweeping motion she would spread the mixture. She said that starting from one area was called a “block”. Each block would follow the other until the entire floor is pasted smooth without any lines or errors shown in the work. As she began to work on the floor, little Suveer Ramroop, a relative of the family ran inside the house to get away from the smell. Despite the old house being surrounded by thriving signs of community progress with newer buildings, growing businesses and paved roads, Ragoonanan said that in her family, only this generation continues this tradition as a means of connecting with their ancestors in India. However, this meant more to the family. The act of leepaying is something that shows the struggles of their family and brings them back to understand and appreciate their forefathers. It may be seen as “dirt work” but the family's message of reminding people that not everything was concrete and tile, and that goobar was used to leepay a house, truly gives meaning to the words, “down to earth.” However, only their generation would be doing this. Ramlakhan explained that the younger generation in his family does not have an interest in continuing the tradition, which he said was sad but something that he will continue to do for as long as he can. He said: “I want to continue doing this because it makes me appreciate my ancestors. It is a humbling experience. The children today don't want to do it but that's alright. My path and my desire to do this brings comfort to me.” Only the living room area was covered with the gobar whereas the rest of the house was being renovated. The family said they would continue to keep just this area “leepayed”. The process has to be repeated several times throughout the year. Source: Daily Express  Fr. Arthur Eugene Anthony Lai Fook was born on July 5th 1919, the youngest of eight children. His parents, Joseph and Jessie Lai Fook, were both of Chinese ancestry; his father was born in China, and his mother was born in Guyana of Chinese parents. In 1904, his parents moved from Guyana to Trinidad with their two eldest children. At first, his parents settled in the village of Penal and owned a shop. His mother, who managed the shop and the children, felt that Arthur would be better taken care of by his sister who lived in Port of Spain. When he was only one year old, Arthur was sent to live in the capital city, where his parents felt he would have better opportunities for a strong educational foundation. Eventually, after the expansion of the oilfields, Arthur’s parents moved to Port of Spain also and the family was reunited. Young Arthur began his primary schooling at Columbus School at the age of five. After two years, he moved to Tranquillity Intermediate School and then to Iere Central High School which was run by Mr. Regis, a strict teacher who provided good academic grounding to his students. In 1930, Arthur wrote the Government Exhibition and placed 11th, gaining a private school exhibition. With this, he entered St. Mary’s College in 1930 to pursue his secondary level education. At St. Mary’s College, Arthur was an average student who was not particularly athletic. At first, he never considered himself to be particularly gifted in mathematics but after solving a geometry problem on the blackboard in Form Three, his interest began to grow. Under the guidance of Father English, School Principal and Mathematics teacher, Arthur set his mind towards his studies in this subject and yielded even greater successes. He tied for fifth place with Valence Massiah in the Junior Cambridge Certificate Examination in 1935 and obtained a House Scholarship. When he repeated the examination in 1936, he obtained the Jerningham Silver Medal, placing second to Ellis Clarke (who was later the first President of Trinidad and Tobago) in the Cambridge Higher School Certificate Examinations in 1936 and obtained the Jerningham Book Prize. He repeated the examination the following year and placed first, copping the Jerningham Gold Medal and an Open Scholarship. After completing his secondary education, he taught at his alma mater for one year, and then left for Paris, where he spent one year in spiritual retreat, testing his call to the vocation of the priesthood. He pursued his tertiary education at the University College of Dublin, a campus of the National University of Ireland. He spent six years there, attaining the Bachelor of Science degree in Mathematics and Mathematical Physics in 1942 and the Master of Science degree in Mathematics in 1943, both with First Class Honours. At the end of his studies, he had also obtained a Bachelor of Arts degree in Mental and Moral Philosophy and a Higher Diploma in Education (1944). He began studies in Theology in 1945 at the Holy Ghost Seminary in Dublin, continuing at the Cantorial University of Fribourg in Switzerland for the Baccalaureate in Theology. He was ordained a priest and became a Member of the Congregation of the Holy Ghost in Switzerland in 1947. In 1948, upon his return to Trinidad, Fr. Lai Fook returned to his alma mater as a Senior Mathematics Teacher. He was responsible for the lower forms as Junior Dean of Studies between 1948 and 1958. He left the college briefly in 1962, when he went to Nigeria. From 1962 to 1964, he lectured in mathematics at the University of Nigeria, where he was also Chaplain to the Catholic students. He returned to Trinidad afterward and lectured at the University of the West Indies at St. Augustine before returning to St. Mary’s College as Senior Mathematics Teacher in 1966. He became Principal of the College in 1971, officially retiring from this position and from teaching in 1978. In 1990, the Government of Trinidad and Tobago bestowed him with the honour of the Chaconia Gold Medal for his contribution to Education. Given his chosen vocations of priest and teacher, one may think that Fr. Lai Fook has had little time to pursue other activities; however, he once was very active in woodworking as a hobby. Working out of a small workshop at the school, he has made several ornamental and functional pieces from benches to cone-holders, glass coasters and letter racks. Despite his official retirement, Fr. Lai Fook continued to teach at St. Mary’s College, first on an eight-year contract, and subsequently on a voluntary basis. It was his decision to continue to serve for as long as he could. Fr. Lai Fook passed away on April 19, 2013 at the age of 93.  Our own Dr. Joseph Lennox Pawan received international acclaim for the discovery of the transmission of the rabies virus by vampire bats. Joseph Lennox Pawan was born in Trinidad on September 6th 1887. He attended St. Mary’s College and won an Island Scholarship in 1907. He attained the Bachelor of Medicine and Surgery degrees from Edinburgh University, Scotland in 1912 and studied at the Pasteur Institute in France.In 1915 he started his career at the Colonial Hospital, Port of Spain as a District Medical Officer and was later appointed Bacteriologist. As the country’s only bacteriologist and pathologist, he provided services for the entire territory in hospital and public health work, as well as bacterial work at the Caribbean Medical Centre. In 1925, many cattle on the island became ill and died suddenly. The same disease killed 13 people in 1929 and others died in ensuing years. The disease, later identified as rabies, was known to be spread by dogs. However, victims were not bitten by dogs and rabies had not been identified in Trinidad since 1914. Pawan and his colleagues J.A. Waterman and H.M.V. Metivier were convinced of a link between the cattle outbreaks and human cases and worked in a simply equipped laboratory to isolate the disease. During research, a woman mentioned being bitten by a bat a month before becoming ill. A. Carini had established in 1913 that vampire bats carried the disease. Pawan knew that bat bites were common in rural districts and completed the puzzle, linking the bat and the bite. In 1932 he and his team isolated the rabies virus from different species of bats including Desmodus rotundus (vampire bat). A vaccine was developed and Pawan was honoured for his hallmark discovery as a Member of the British Empire (MBE) in 1934. He also discovered that sleeping sickness in livestock was due to disease-bearing insects from the South American mainland. He retired in 1947 but continued to work part-time at the Colonial Hospital. In 1954 he became a consultant on rabies to the US Government. He was invited to work for the World Health Organization but declined due to poor health. Hospitalized for the last three years of his life, Dr. Pawan passed away on November 3rd 1957. The Pan American Health Organization named him a “Hero in Health” in 2000 for his contribution to public health.  Books by nine writers, the majority under the age of forty, have been announced on the longlist for the 2017 OCM Bocas Prize for Caribbean Literature, sponsored by One Caribbean Media. Now in its seventh year, the Prize recognises books in three genre categories — poetry, fiction, and literary non-fiction — published by Caribbean authors in 2016. In the poetry category, the judges have named books by three younger Jamaican writers. Ishion Hutchinson’s House of Lords and Commons is a meditation on home and abroad, personal and communal history, with a rich verbal register and intense engagement with the past literary canon. Ann-Margaret Lim’s lyrical Kingston Buttercup has a deep grounding in the landscape of Jamaica, whether the penetrating poems address the persistent legacy of slavery, Lim’s relationship with her mother, or the complications of contemporary Kingston. And Safiya Sinclair’s debut Cannibal is haunted by the character of Caliban from The Tempest, as it explores Jamaican childhood and womanhood, and otherness in a strange place that may be the United States where the poet now lives, or language itself. “We were delighted to read a set of poetry collections remarkable for their range of focus and poetic method,” write the prize judges. “Each entry made its own claims on us in terms of originality, appeal, and ambition. Throughout our discussions, all the collections impressed upon us the vitality of today’s voices in contemporary Caribbean poetry.” The fiction category includes novels by two Jamaicans and one Trinidadian. Marcia Douglas’s magical realist novel The Marvellous Equations of the Dread is set at one of the bleakest moments of Jamaica’s recent history, after the deaths of Bob Marley and Emperor Haile Selassie, and conveys a sense of both history’s dread and the hope born of human creativity. In his debut novel The Repenters, Kevin Jared Hosein tells a transgressive, almost gothic tale of violence and punishment, exploring the darkest side of Trinidadian society and family history. And in Augustown, Kei Miller offers a historical epic ranging over sixty years of Jamaican history, with its complexities of class, ethnicity, religion, and language. “Due to the excellence and range of so many of the works, selecting a shortlist was extremely difficult,” remark the fiction judges. “We were impressed by the high quality of the entries drawn from a range of new and established writers across the region and beyond. The immediacy of their respective concerns for their culture and their pride in the richness of its history are obvious. They’re digging deep.” The final longlisted books, in the non-fiction category, are all historical studies. Barbadian Hilary McD. Beckles’s The First Black Slave Society: Britain’s “Barbarity Time” in Barbados, 1636–1876 is a compelling history of the first 140 years of the colonisation of Barbados, “with great resonances for contemporary debates about reparatory justice for the crimes of history,” say the judges. Angelo Bissessarsingh’s twin books Virtual Glimpses into the Past and A Walk Back in Time, considered by the judges as two volumes of a single work, collect vignettes from the history of Trinidad and Tobago, offering an effortless read for those for whom the past is a forgotten country. Bissessarsingh, a self-taught historian who passed away in early 2017, during the judging period, won a devoted following among Trinidadian readers for his enthusiastic style and passion for research. And in Inward Yearnings: Jamaica’s Journey to Nationhood, Colin Palmer tells the story of Jamaica’s struggle to define an identity that embraces both its African heritage and its Anglophone western past. “Palmer’s prose immediately immerses you in sympathy for the people, events, and organisations that make this history,” the judges note. The winners in each genre category will be announced on March 27 and the Prize of US$10,000 will be presented to the overall winner on Saturday, April 29 during the seventh annual NGC Bocas Lit Fest in Port-of-Spain. The 2017 judging panels for the OCM Bocas Prize bring together distinguished Caribbean and international writers, academics, and publishing professionals. David Dabydeen, the celebrated Guyanese writer based in the UK, chairs the poetry panel, which also includes Cuban poet and translator Nancy Morejón and London-based agent Peter Straus. On the fiction panel, chair Susheila Nasta, founder and editor of the journal Wasafiri, is joined by New York–based agent and editor Malaika Adero and St. Vincent-born, Canada-based writer H. Nigel Thomas. And Jamaican Kim Robinson-Walcott, editor of Caribbean Quarterly and Jamaica Journal, chairs the non-fiction panel, which includes scholars Aaron Kamugisha of Barbados and Patricia Mohammed of Trinidad and Tobago. The overall chair of the 2017 cross-judging panel is the eminent Jamaican poet and scholar Edward Baugh. Source: Loop news  Two local Attorneys are currently representing Trinidad and Tobago at a two-week internship at the prestigious Osgoode Hall Law School, York University, in Toronto, Canada. Attorney-at-law Shoshanna V. Lall, the Senior Legal Officer in the Office of the President, is one of four attorneys from an international list of 100 applicants to have won the internship. Lall’s Research Project, “Modernising Justice: Mandatory Mediation in the Trinidad and Tobago Justice System, E-filing and Legislative Reform” and the 45-minute interview, which followed her being shortlisted, earned her a place as one of the 4 Legal Research Interns at Osgoode Hall Law School. Among the four selected interns is another Trinidad and Tobago Attorney-at-Law, Kamla Braithwaite, who is a Judicial Research Counsel in the Judiciary of Trinidad and Tobago. Her Research Project concerns “Access to Justice for Litigants in Trinidad and Tobago.” The Internship runs from March 6 to March 17, 2017 at Osgoode Hall Law School and will continue with the submission of a legal paper, presentations and the further action required for implementation of the Research Project in the civil justice system. This International Legal Research Internship, financed by Global Affairs Canada (GAC), was offered through the Justice Studies Centre for the Americas (JSCA), in collaboration with Osgoode Hall Law School (OHLS), on the platform, “Improving Access to Civil Justice in Latin America”. Applications were invited from international attorneys-at-Law practicing in various fields of law- public and private- on a topic of their choice, which supports civil justice reform in the Region, in the area of civil procedure. Source: Loop |

T&T news blogThe intent of this blog is to bring some news from home and other fun items. If you enjoy what you read, please leave us a comment.. Archives

May 2025

Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed