|

In commemoration of the 142nd Anniversary Celebrations of Princes Town. Author : Angelo Bissessarsingh

In 2014, my friend and fellow historian, Richard Charan and I , embarked on an epic journey to find the remains of a long-forgotten 19th century sugar baron, Harry Darling, and in the process, unearthed stories of the Princes Town area that were documented In his parent paper and provided a valuable insight into how life was in those times. I assisted his researches and in the process stumbled upon some interesting gravestones in the unkempt and vandalized cemetery of the St. Stephen’s Anglican Church. They all stood in a forlorn cluster, away from the tombs of sugar planters, old parishioners and other prominent persons. The weathered and barely legible inscriptions were also noteworthy and showed some age, a couple examples being “In Memory of Frederick Maing, died 1st March 1905” and “In loving memory of our dear George Amow, died September 12th 1895 aged 38 “. Each marker, aside from the English epitaph,had Chinese script engraved on the marble tablets. Across town in the slightly better maintained graveyard of the Holy Cross Roman Catholic Church was another fascinating marker which used Scottish firebrick and Spanish clay tiles to create a rude pagoda which enclosed the remains of Louis Atteck who died on the 12th of September 1888. It is possible that Louis was an ancestor of the late Sybil Atteck whose artistic genius brought Trinidad and Tobago into the realm of modern art. Princes Town itself began life as the Mission of Savanna Grande. Founded in 1687 for the conversion of Amerindians to Christianity, it remained a sleepy village of First Peoples until the final disbanding of the mission in 1840. The Amerindians receded into history to make way for King Sugar. The Naparimas were the richest sugar lands in the island and Savanna Grande was its inland capital. Connected to the port of San Fernando by the island’s first railway in 1847 (the Cipero Tramroad), the settlement was a rip-roaring one where sugar planters mingled with ex-slaves, indentured immigrants from India and of course, the Chinese. The presence and industrious nature of the latter was noted by Charles Kingsley when he visited in 1870: “Then to church at Savanna Grande, riding, of course ; for the mud was abysmal, and it was often safer to ride in the ditch than on the road. The village, with a tramway through it stood high and healthy. The best houses were those of Chinese. The poorer Chinese find peddling employments and trade about the villages, rather than hard work on the estates; while they cultivate on ridges, with minute care, their favourite sweet potato. Round San Fernando, a Chinese will rent from a sugar-planter a bit of land which seems hopelessly infested with weeds. The Chinaman will take the land for a single year, at a rent, I believe, as high as a pound an acre, grow on it his sweet potato crop, and return it to the owner, cleared, for the time being, of every weed. The richer shopkeepers have each a store : but they disdain to live at it. Near by each you see a comfortable low house, with verandahs, green jalousies, and often pretty flowers in pots.and catch glimpses inside of papered walls, prints, and smart moderator-lamps, which seem to be fashionable among the Celestials. But for one fashion of theirs, I confess, I was not prepared. All that could be told was, that the richer Chinese take delight in thus bedizening their wives on high days and holidays ; not with tawdry cheap finery, but with things really expensive, and worth what they cost, especially the silks and brocades ; and then in sending them, whether for fashion or for loyalty's sake, to an English church.” With all the commerce around, some Chinese became cocoa proprietors as well as merchants. The lands to the north and east of Princes Town (so called after a Royal Visit in 1880) were divided into many small estates of five and ten acres. These could be easily planted and tended with the expert labour of Venezuelan cocoa panyols and in the cocoa boom of the late 19th and early 20th centuries, guaranteed a good income. The conversion of many Chinese to Christianity in the Prince Town area is proof of how rapidly these hardworking people integrated into Trinidadian society, dispelling the stereotype of the Orientals being silent and aloof. Today, there are still descendants of the many Chinese who once were a force to be reckoned with in the Naparimas.

0 Comments

- Angelo Bissessarsingh ( Historian & Researcher)

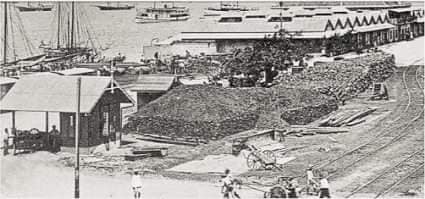

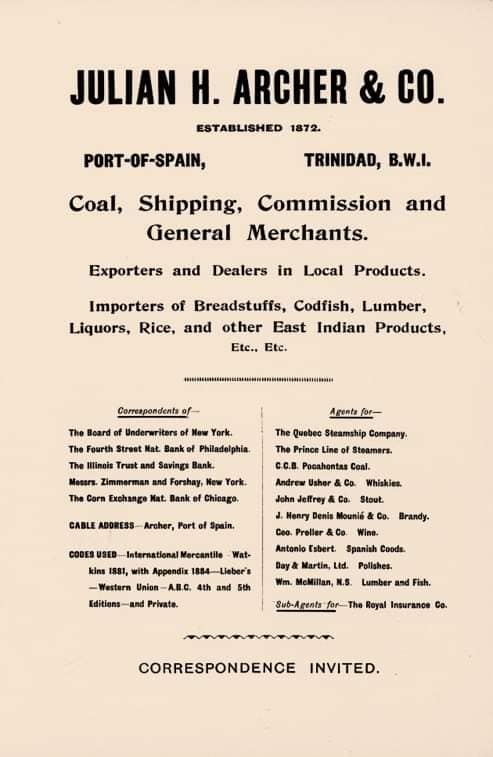

Life during crop time was characterized by lengthy days, punctuated at noon for a meal of rice or roti and talkaree under the blazing sun amid cut canes. And yet this was the necessary sacrifice for the children of the cane to escape the bondage into which their ancestors had tied themselves since 1845. Children of the cane grew up with hard, scratched palms from the endless chores of gathering firewood, tending livestock, or for the hapless many, work in the “grass gangs,” uprooting the tough weeds that sprang up among the rationing canes in the rainy season. Those whose parents could afford the uniforms and books usually went to the Canadian Mission (Presbyterian) school, of which there was one in almost every sugarcane belt village by the early 1900s. Although illiterate, the parents were aware that within these humble schools lay the escape from the cane.. 1940s photo, shows a young boy stripping a piece of cane with his teeth.. (Source: Virtual Museum of Trinidad and Tobago) The heap of coal on South Quay around 1910 A 1904 advertisement for the Archer business concerns Author : Angelo Bissessarsingh.

Port-of-Spain has one of the finest natural harbours in the world. Being almost completely landlocked, it is not susceptible to swells or powerful currents which would make for a dangerous anchorage. Its only failing is that the water was not deep enough for ships to draw alongside the quay, a dilemma which was not remedied until the construction of a deep water harbor in 1931. Nevertheless, the port was a busy place for ships calling from all parts of the world, and coaling was a major economic activity. With the coming of steamships in the 1820s, sailing vessels took a back seat although were not entirely obsolete. Some steamships even boasted masts and sails in case the boilers burst (a not uncommon occurrence due to poor metal castings). Trinidad was a great port of call for many large shipping lines including the Royal Mail Steamship Packet Company and the White Star Line, owners of the infamous Titanic. Local firms like Geo. F. Huggins and Trinidad Shipping and Trading Company also possessed their own steamships. With so many steamers around, an indispensable necessity was coal, and large quantities thereof. Lignite, a low-grade coal, occurs in Trinidad (Sangre Grande, Irois, Savonetta) and was identified in 1860 by geologists Wall and Sawkins. These lignite deposits, although substantial were never exploited commercially due to the low price of the commodity and high production costs. Manjack, a brittle form of graphite-matrix bitumen was mined profitably at Vistabella and Williamsville in south Trinidad from the 1890s to the 1920s. Despite these local sources, the bulk of the coal used in the colony was imported from England and the United States. Aside from use in steamships, coal was also indispensable for the railways of the island. The first local steam locomotive, the Forerunner, traversed the rails of the Cipero Tramroad between Princes Town and San Fernando as early as 1864. The Trinidad Government Railway began operations in 1876 and also needed coal since oil-fuelled locomotives would not appear until the 1920s. Added to this, large sugar manufacturing concerns had their own private railways leading to central factories at Orange Grove, Usine Ste. Madeline, Reform, Brechin Castle, Woodford Lodge and Forres Park. The English-creole Archer family,and its patriarch, speculator Julian H. Archer had been movers and shakers in the local economy for many years , being founders of the Trinidad Building and Loan Association and the Trinidad Fire Insurance Co. Established in 1872, the company did good business in the booming Trinidad economy which was riding the tide of high cocoa prices and a spike in production. William Stedman Archer, a son of Julian , diversified the family holdings to cater for the ever increasing need for coal. Although there were other importers of the fuel Archer’s Coal Depot soon seized the lion’s share of the market. This was so for several reasons. Firstly, Archer’s had a regular supply of the best quality coal, being a subsidiary of sorts of the Berwind White Coal Company which had its own mines in Pennsylvania, supplying a bituminous , high grade of coal which did not produce as much residue and smog as lower grade stuff. Originally stockpiled in the open air the fuel was eventually stored in a massive warehouse, since storing coal exposed to the weather reduced its combustibility. Secondly, the firm owned a fleet of tugs and barges which catered for the fact that larger ships could not dock alongside the St. Vincent St. Jetty, so Archer’s took the coal out to these clients. The business’s office was on Broadway and its warehouse at South Quay. The company was managed from 1912 by A. Cory Davies, an Englishman who had come out to the colony as a clerk in the Colonial Bank in 1895. The advent of the oil age in 1912 posed a not inconsiderable threat to the coal business, although wholesale displacement of steam engines by diesel engines was still at least three decades away. In 1913-14, Trinidad Leaseholds Ltd. began oil production at Barrackpore near Penal, and Forest Reserve near Fyzabad, with the crude being pumped to its refinery at Pointe-a-Pierre for conversion into gasoline. Regent Petrol, the brand produced by T.L.L was also sold by Archer’s who secured the distributorship for P.O.S where the motor car was becoming a popular sight on the road. The petrol was sold in large drums to motorists since there were no gas stations until around 1918. Archer’s coal depot was in business well into the 1930s until it closed for good. (Source: Virtual Museum of Trinidad and Tobago) Chris De La Rosa, Tosin Ayeronwi of Ottawa among Canadian creators chosen for the fund. Chris De La Rosa wants you to know that you can make Caribbean food no matter where you are in the world. "It's important for me to put all food and all culinary culture in a positive light," he said. "And not just that, but in a niche that breaks it down so anyone can make it no matter where in the world they're based." The Hamilton-based creator does all that and more on his channel, CaribbeanPot — which is shy of 800,000 subscribers. His videos have also garnered a combined total of 90 million views. De La Rosa's channel is the YouTube counterpart of CaribbeanPot.com, a blog he started as a way to collect recipes for his kids to make someday and document the rich cuisine he enjoyed while growing up. Now, the channel is part of #YouTubeBlack Voices class of 2022, where creators on the site receive funding and support to help grow and enhance their YouTube channels. YouTube announced the program in a 2020 blog post that outlined a multi-year, $100-million fund to amplify and lift Black voices and ideas. De La Rosa is one of five Canadian creators — including Tosin Ayeronwi of Ottawa — who have been chosen for the fund. With additional funding, he plans to tell the bigger stories behind the food he makes. "I want to tell the stories further of not just the food, but where the food comes from. I want to tell that story as well. I don't want to always be in the kitchen." Many of the meals De La Rosa knows and grew up with aren't documented, and they don't have precise measurements. "I had to create everything from scratch," he said, "and I wanted it to be very easy for them to recreate the flavours that they enjoyed growing up, even right here in Canada." Growing up in Trinidad, he said, everyone knew how to cook — whether you were a boy or girl.

"My parents have two boys and two girls, and they never assigned gender roles back then as would be normal in the Caribbean and many other places," he said. "My mom always wanted her sons, especially her boys, to be independent and do their own thing." When he was in his mid-teens, De La Rosa immigrated to Canada, where he lived with his aunt and cousins in Hamilton. Inspiring other Black creators After he was required to make some of the meals, he realized he wanted to have a taste of home again more than ever before. "When [...] it's -20 degrees outside, it's overcast, it's snowing, you want to feel like you're part of the Caribbean again." When it comes to reaching out to other Black creators on YouTube, De La Rosa finds his inspiration is helpful to those creating similar content. "If you look now, you'll find 15, 20, 30, 40 different channels with the same sort of topic that I've been doing since 2009. And if you look closely at the way they present their work, the way they edit, the way they shoot, the way they speak on camera, you will see elements of my channel on those. "I have personally reached out to a lot of these other YouTubers, these Black YouTubers, Indian YouTubers — whatever race they are, and I say, 'Can I help, how can I help? I've been doing this for so long.'" 'The space has room for everyone'Although what they do can come across as copying the content that he creates, De La Rosa reminds himself the creative space of YouTube and other online platforms is for everyone. "The space has room for everyone," he said. "It's not a competition." (Source: CBC News, Feb 8, 2022) |

T&T news blogThe intent of this blog is to bring some news from home and other fun items. If you enjoy what you read, please leave us a comment.. Archives

July 2025

Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed