|

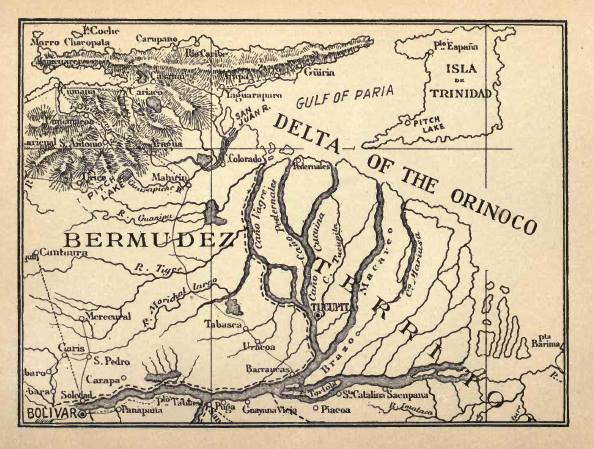

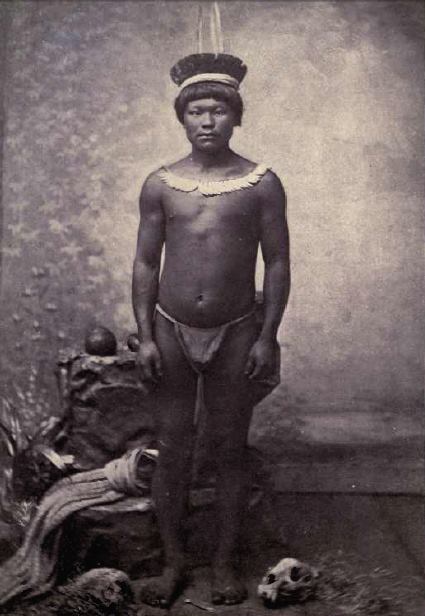

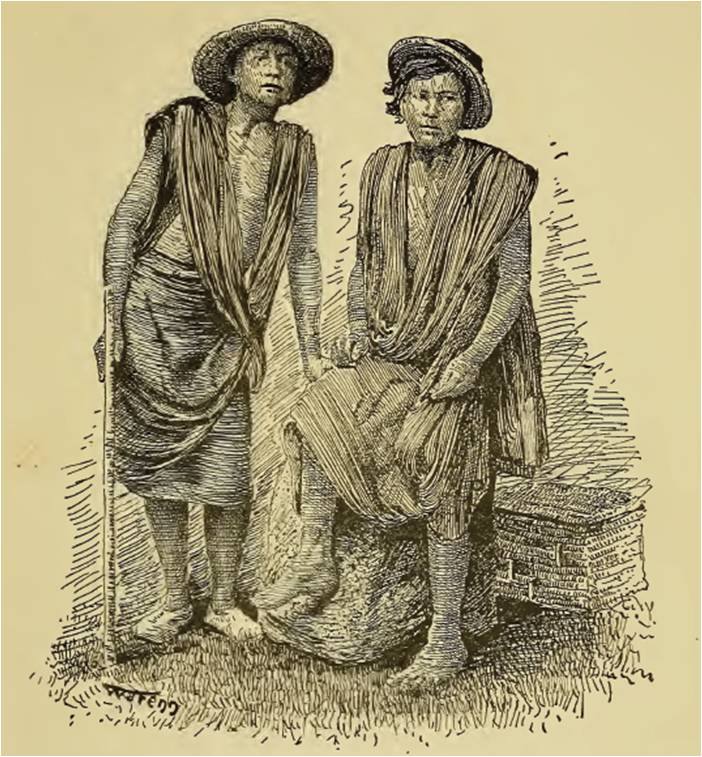

By Angelo Bissessarsingh, Historian and Author (2014) Old map showing the proximity of Trinidad to the Orinoco Delta Sketchy school textbooks have taught generations of Caribbean children numerous myths about the region’s First Peoples such as the conflicts between the savage Caribs and peaceful Arawaks when in reality, there were many different cultures and languages. Around eight thousand years ago, a small band of Neolithic peoples crossed a narrow land bridge from the continental mainland of South America into Trinidad. They carried little, save perhaps a few treasured ceremonial artefacts made of greenstone that had been quarried from the misty heights of the Roraima Mountains. In the south-western part of Trinidad they founded two settlements on the fringe of a mangrove swamp which provided all the necessities of life Banwari Man, the oldest human remains in the Caribbean. These peoples were hunter-gatherers and lived off the bounty of nature- from the roots of the mangrove they plucked oysters whose discarded shells formed a great refuse heap that over a millennia of unchanged habitation grew to be a hill almost twenty feet high. The fruits of the wild and the starchy bulbs of water plants were their vegetables, pounded and processed with simple stone tools. Small land mammals were hunted for meat with bone-tipped spears. Bone was also used to make bi-pointed fishhooks. Crude stone axes felled small trees which were used to make round huts. Cut off from the mainland by rising sea levels. This wave of hunter-gatherers eventually developed the technology to manufacture dugout canoes and may have reached Tobago. Their remains have recently been discovered in Barbados as well, but their presence in Trinidad makes this island the oldest inhabited place in the Caribbean. In the 1960s and 70s the shell mound , located in what was by then known as Banwari Trace in the sleepy village of San Francique, was excavated by the late Peter O’Brien Harris and yielded the remains of Trinidad’s oldest ‘resident’. Banwari Man (or woman) is a human skeleton approximately five thousand years old that was found buried in a foetal position. A tenuous cultural and anthropological connection has been established between Banwari Man and the present-day Warao First Peoples of the Orinoco Delta in Venezuela. It is now housed at the University of the West Indies Zoology Museum at St. Augustine. Persons wishing to view the skeleton and interesting specimen collection can contact curator Mike Rutherford at 1 (868) 662-2002 ext. 82231. In the wake of the archaic hunter-gatherers came waves of pottery-making cultures beginning in 250 B.C A man from the Warao people of the Orinoco Delta (1897). The Warao are believed to be related to the neolithic hunter-gatherers who inhabited Trinidad over 8,000 years ago These were peoples from the Orinoco Delta and their ceramics were durable and highly decorated. The adornments were fanciful heads and shapes in clay which anthropologists have identified as an intense theological phenomenon rooted in religious practices that deified zoomorphic (animal) and anthropomorphic (human) spirits. The earliest pottery cultures are known as Saladoid because the ceramic style was first classified at Saladero in Venezuela. Later movements of first peoples came to Trinidad and brought with them new agriculture, lithics (stone-tool tech), and ceramics. Their refuse heaps or kitchen middens can be found throughout the island and several are very extensive indeed. One such discovery was recently made under the foundations of the Red House in Port-of-Spain which was erected in 1848 and until its recent renovation began, housed the Parliament of Trinidad and Tobago. The find included potsherds and human remains. Up until the 1930s, Warao peoples (seen here in 1912) from the Orinoco Delta visited coastal towns in Trinidad to trade parrots, hammocks and wild game for clothes and other merchandise.  Although Columbus stumbled upon the island in 1498, the waning of the Amerindian presence in Trinidad came in the wake of the first permanent Spaniard settlement at San Jose de Oruna (St. Joseph) in 1592. Those natives not killed off by disease or overwork were herded into small villages called Encomiendas which were little more than serfdoms under the control of a Spanish grandee. The alternative from 1687 was residence in one of the several missions established by Capuchin monks which were only mildly preferable to the Encomiendas. An uprising at the mission of San Francisco de los Arenales (near present-day San Rafael village) saw the Amerindians slaying three priests before being pursued and brutally punished. The missions were really the end of Amerindian culture since they adapted into the Spaniard mode of existence. The missions lasted after the British conquest of 1797 and were dissolved in 1840. The mission villages became desolate and the people in them resigned to their fate. In 1825 a rare diary entry gave a glimpse of what they had become: “They seem to be the identical race of people whose forefather Columbus discovered, and the Spaniards worked to death in Hispaniola. They are short in stature, (none that I saw exceeding five feet and six inches,) yellow in complexion, their eyes dark, their hair long, lank, and glossy as a raven's wing ; they have a remarkable space between the nostrils and the upper lip, and a breadth and massiveness between the shoulders that would do credit to the Farnese Hercules.  A large stone axe discovered at Cedros in 2011 (Angelo Bissessarsingh Collection) A clay zoomorphic artifact dated to an age of around 1500 years that was found at Erin Bay in 2009 (Angelo Bissessarsingh Collection) Their hands and feet, however, are small-boned and delicately shaped. Nothing seems to affect themlike other men ; neither joy nor sorrow, anger nor curiosity, take any hold of them. Both mind and body are drenched in the deepest apathy; the children lie quietly on their mothers' bosoms; silence is in their dwellings.” Arima was the largest and still retains vestiges of its past as well as a vibrant First Peoples group, the Santa Rosa Carib Community which dedicates itself to the preservation of native culture and championing indigenous affairs. Annaparima (San Fernando Hill) is a sacred site and is now visited annually by First Peoples including the Warao of the Orinoco Delta who perform religious ceremonies there. A slow but sure interest in the truths of our first settlers is now firmly rooted and hopefully will continue to grow. Cassava bread was an essential part of indigenous diets in the West Indies. It is still made at the Santa Rosa Carib Community in Arima . This 19th century engraving shows the discs of bread hung out to dry after which it can be stored for months.

0 Comments

Leave a Reply. |

T&T news blogThe intent of this blog is to bring some news from home and other fun items. If you enjoy what you read, please leave us a comment.. Archives

June 2025

Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed