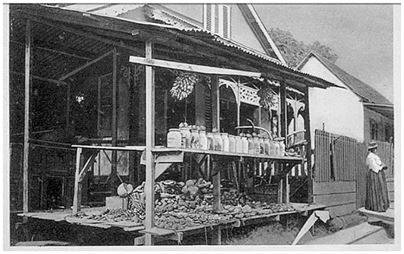

James Cummings, in his seminal work on The Barrack-Yard Dwellers, said, “For the people of the barrack-yards, the sun just had to rise tomorrow.” By this he meant that decades of economic penury in the post-emancipation urban space, leading up to the massive slum clearance exercises of the 1950s, had made the dwellers of the poorer parts of Port-of-Spain masters of coping with poverty. In the areas of Queen Street, Charlotte and Quarry Street where the barrack-yards proliferated, there were occasional wooden cottages owned by more “respectable” coloured people, Venezuelan refugees fleeing political unrest, and white people of reduced means. Many of them would be on the verge of not knowing where tomorrow’s bread would come from. One coping strategy was to open a small “one-door” shop in the front premises of one’s house. This could be in the porch or as a wooden extension. The stateroom at the front of a house is commonly called a parlour. Since these makeshift shops often occupied the aforementioned space, the enterprises themselves became known as parlours. Few, if any, Trinidadians are aware that this was how these vital community establishments came to be called thus. The parlour, in urban and rural areas, became a focal point of social interaction where people, young and old, could meet and exchange the latest gossip. Parlours of yore were places where the fare was manufactured almost entirely by local hands and where simple treats meant so much. They were tenuous businesses where tiny profit margins made their proprietorship more a community service than a get-rich-quick enterprise. For children of yesteryear, there could be few pleasanter places. Large glass jars would be filled with sugar-coated paradise plums, kaisa balls, tangy tamarind balls, molasses-dripping toolum, pink sugar cake and paw-paw balls. A huge block of ice, delivered by a cart in the early morning, would be resting on a piece of sacking, swaddled in straw to keep it from melting too quickly. This ice, of course, would be vigorously shaved, rammed into a metal cup and then covered in sweet, red syrup for a penny, and for another copper, laced with condensed milk to result in that much-relished treat, snowball. Outside of the city and in the countryside, there were parlours too, mostly run by “celestials with pig-tails and thick-soled shoes grinning behind cedar counters, among stores of Bryant’s safety matches, Huntley and Palmer’s biscuits, and Allsopp’s pale ale...” this according to Charles Kingsley, writing in 1870 about a Chinese parlour in the deep countryside. The country parlour often was the oasis of rural travellers, according to one account from 1914: “Restaurants are rare in the West Indies, except in the principal towns, but it is generally possible to obtain something of a simple kind, which on this occasion consisted of that nice aerated drink called kola, together with buns from a stall at the entrance of the same shop.” So then, this is the origin of the parlour, a small-business model which still thrives today. 1908 photo of a parlour in east Port-of-Spain , where the business model developed. In addition to jars of pickles and sweets, this little wayside emporium also sells a variety of fruit and vegetables. Source: Virtual Museum of Trinidad & Tobago

0 Comments

Leave a Reply. |

T&T news blogThe intent of this blog is to bring some news from home and other fun items. If you enjoy what you read, please leave us a comment.. Archives

April 2025

Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed