|

Credit to Author , Angelo Bissessarsingh.

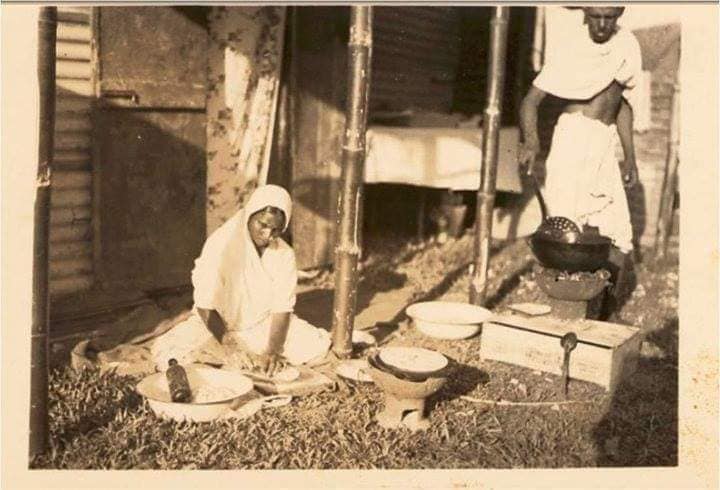

Disclaimer : Article was written by Angelo and in no way intended to offend persons of East Indian descent. Photo credits.. Anthropologists Arthur and Juanita Niehoff. “Cool..e, cool... come for roti, all de roti done.” This was the refrain that haunted many of the formerly indentured Indian immigrants in Trinidad and their descendants from their arrival almost to and including the present day. There is no immigrant story that comes without some painful recollections. It is a testimony however to the spirit of ALL Trinbagonians, that we have managed to grow beyond these recriminations and become a more unified people DESPITE the will of divisive elements such as politicians and pseudo-religious leaders. It seems odd now in a society that counts doubles as a staple food, and where roti has almost epicurean status in some places, that the derision of the Indo-Trinidadians and their food was once commonplace. One of the first articles I wrote for this newspaper back in 2012, was on the roots of Indo-Trinidadian gastronomy which is anchored firmly in the rations which the labourers received during their contracted residences on the sugar plantations of the island. Though the provisions were sometimes augmented or differed according to the estate, the general issue was as Charles Kingsley described it in 1870: “Till the last two years the new comers received their wages entirely in money. But it was found better to give them for the first year (and now for the two first years) part payment in daily rations : a pound of rice, 4 oz. of dholl, a kind of pea, an oz. of coco-nut oil, or ghee, and 2 oz. of sugar to each adult ; and half the same to each child between five and ten years old.” The variations would usually be the addition of a small quantity of saltfish, dried pepper or potatoes. Eked out by provision gardens, often planted with crops brought from India as seeds in the ‘jahaji’ bundles of the labourers, it laid the foundation of a spicy food culture which is as different from anything produced in India today. Those who have dined on authentic Indian dishes will attest to the immense difference from the deliciously creolized creations of Trinidad. Diversification of the Indo-Trinidadian palate came about in the 1880s when many shopkeepers realized what was necessary to attract a clientele from this ethnic group. Wholesalers began to import a variety of spices and curry ground with a ‘sil and loorha’ became more commonplace. Large quantities of ghee, channa (chickpeas). Essentials like mustard oil began to make their appearance at both rural and urban grocers. Nevertheless, Indo-Trinidadian cooking remained an ‘underground’ scene, unknown to most other ethnic groups and rarely tasted outside of the mud huts where it was prepared unless one was invited as a guest. Tempting talkarees, rotis and meetai (sweets) churned out in the aromatic smoke of an earthen chulha (fireplace) were a well-kept secret, not by dint of cultural isolation alone, but also because of a growing sense of shame and self-loathing. Indo-Trinidadian children who attended government schools or schools operated by denominations other than the Canadian Presbyterian Mission to the Indians (CMI) were ridiculed for the lunches they carried, usually sada roti and some sort of bhagi or talkaree. It inculcated a massive inferiority complex which many carried into adulthood. This is well-remembered by persons today and finds its way into Caribbean literature such as the works of Sir V.S Naipaul and Ismith Khan. Well through the 1930s, Indo-Trinidadian concoctions was looked down upon as ‘hog food’ or fit only for the poorest classes. In a calypso sung by the Roaring Lion, he noted the cheapness of the diet by the chorus: “Though depression is in Trinidad, maintaining a wife isn’t very hard, Well you need no ham nor biscuit or bread for there are ways they can be easily fed, like the coolies on bargee, pelauri dhal-bat and dhal-pouri , channa, paratha and the aloo-ke-talkaree” Even doubles at its genesis in the hands of Enamool Deen in Princes Town was viewed as lowly stuff, unfit for consumption by all but rumshop drunks and hungry schoolchildren. In a memoir written by his son, Badru Deen, the struggle to introduce doubles to the urban consumer in San Juan and Port of Spain is well documented. It would be many decades before Trinidad’s most celebrated street food found a place in the national palate. As a fast food, roti was almost non-existent in the towns like Port-of-Spain where it only began to appear in the 1940s during World War II. Roadside roti-stalls were set up with all the necessary utensils, including several coal-pots, churning out dhalpouri with fillings of curried beef (ironic and at once immensely popular), goat, and curried aloo. Chicken a more expensive option. Some rumshops owned by Indians served roti as well. It is a long and stony road that Indo-Trinidadian cuisine has travelled to gain the universal acceptance it enjoys today. (Source: Virtual Museum of TT, May 11, 2023)

0 Comments

Leave a Reply. |

T&T news blogThe intent of this blog is to bring some news from home and other fun items. If you enjoy what you read, please leave us a comment.. Archives

May 2025

Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed