|

On Christmas Eve 2011, William Edwards died at the San Fernando General Hospital, three days after falling ill. He was 87 years old and had outlived his wife, only child and every sibling. Edwards, who lived alone in his final years, was considered by some as a recluse, so his passing was unknown to many in his village of Brothers, Tabaquite.

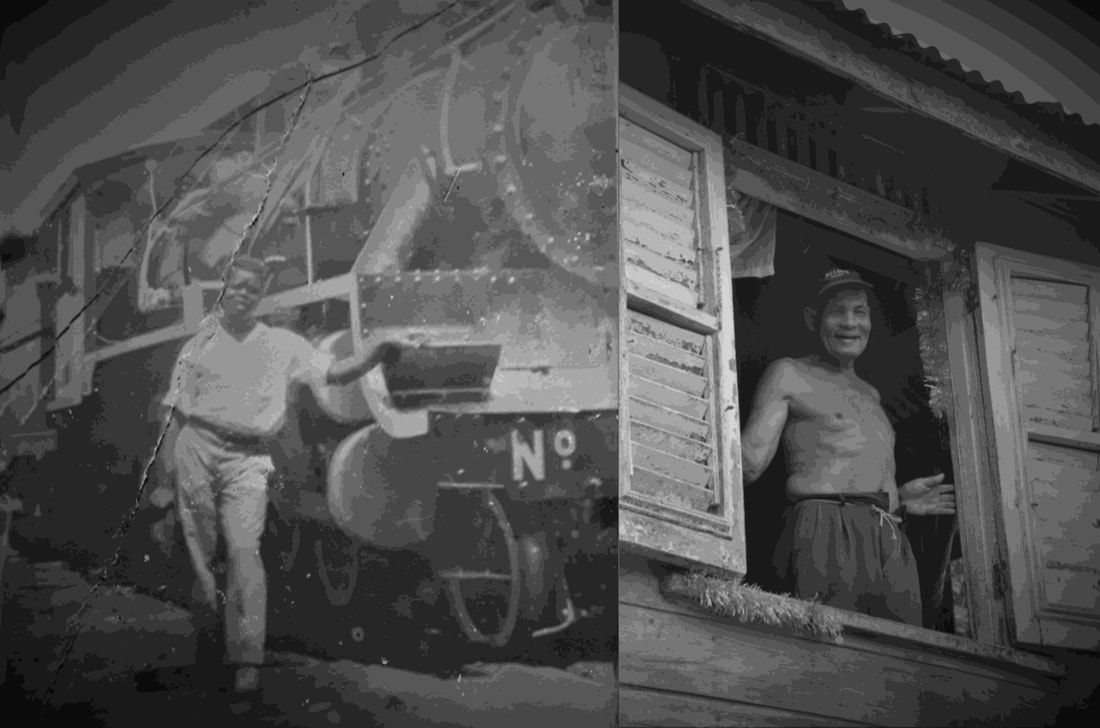

Only a small circle of family and friends attended the funeral at Belgroves Crematorium to send him off. But a peculiar thing happened in the weeks following his passing. As news began trickling through the village that he had died, memories stirred, and “Eddie” was alive again in the mind’s eye of those who remember him. There he was, leaning out the open window of a locomotive, sounding the steam whistle, calling out to neighbours as his engine pulled the carriages carrying people, produce and cargo along the train line linking Rio Claro to the rest of the island. It turns out that Edwards, who found employment as a boilerman at Trinidad Government Railway (TGR) on June 30, 1942, had worked his way up to being an engine driver. He was in charge of one of the engines that travelled a system extending between Port of Spain and as far as Siparia, Sangre Grande and Princes Town. By the time his employer made him redundant and sent engine driver Eddie home on October 25, 1966, he was a man with a skill no one needed. He would later find employment as a wardsman at the same hospital where he would die. Last train For the citizens who used the line between Jerningham Junction and the stops in Longdenville, Todd’s Road, Caparo, Brasso, Tabaquite, Brothers, San Pedro and Rio Claro, Eddie would always be remembered as the man who drove the train to Rio Claro the last day it ever carried passengers—August 30, 1965 (the same day of the celebrated “Last Train to San Fernando” from Port of Spain). The Express spent several days following the path of the railway out of Rio Claro to discover that two generations after the end of the rail, many still have vivid memories and unresolved complaints. Some blame the economic and infrastructural decline over the decades on the State’s decision to replace the railway with buses. People wanted to know why no one had thought to preserve the TGR buildings, signal boxes, road crossings and platforms. The people of Dades Trace where a TGR building still exists, asked why no one had maintained the impressive homes of the station masters—Coudray, Villafana, McAllister, Mitchell, Superville, McIntosh—who were of significant social standing. Like clockwork Does anyone know how important this rail line was back then, asked villager Lucy Ashby. She said that back then, it was either the train or having to foot it out of her village of cocoa plantation workers. Now, the only evidence of its existence, said Ashby, were the concrete and steel bridge crossings too difficult for scrap dealers to steal. Her sister, Angela Charles, who paid four cents to travel by train into Rio Claro to see Carnival in the ’50s, said she often wondered what would have become of her life if the train, which allowed travel into the capital, had continued operating. Khairoon Shah, who was 88 years old when we spoke with her, said as a newlywed, she was walking the kilometre or so to Brothers Station as far back as 1942 to catch the train to visit her family in Libertville. “That engine was loud and you knew it was coming from the long trail of black smoke from the chimney. One headed up to Rio Claro for 9 a.m., passing back at 11 o’clock. Another went up at 2 p.m. and back down at four. And the train was always there on the exact time, bringing people and mail, bread, ice, carrying back cocoa and coffee and sugar cane. So you had to be there or you lose out,” she said. Shah said on the final day the passenger train rolled, “Edwards was the one who drove it from Jerningham. They gave a free ride and we rode all day and in the night.” Her son, Khairoon Shah, said he, too, as a teenager, understood something big and sad was happening that day when the seven cent fare from Brothers Station to Rio Claro was waived. “They never should have scrapped it. The village felt connected then. When it stopped running, it killed this area,” he said. Photographic memory As a result of a series of fortunate events, one of the most substantial Trinidad Government Railway buildings outside of Port of Spain still exists where the Brothers Station stood. The family of the ticketmaster remained occupants of the building when the train service ended, and on January 13, 1975, it was acquired by Stephen Subero, himself a lifetime worker with the railway. The building, likely used by the stationmaster, comprises a living area, three bedrooms and a detached kitchen, which prevented the entire house from going up in flames in the event of a fire there. The outhouse is also still there, along with two concrete cisterns to supply the property, locomotive and passengers of the time. Subero, who raised ten children in that building, recalled when the carriages pulled up and villagers came with their bull and donkey-drawn carts to collect the items they had purchased from “town”. “Let nobody fool you, nothing about the rail was easy. My father (Henry Ayers) had the job of checking the line (all 13 or so kilometres) from here to Rio Claro before 6 a.m. to make sure no big tree fall across. Only when he say so, the train would run,” he said. Despite a hard life, Subero said he recognised early that the building in which he made a life was different. “People from all over Trinidad have come here to ask questions about the train and take photographs. I never had photos because back then it was survival. I walked barefoot for the first 36 years of my life. But these people who come here want to learn about the railway. They amazed this place still here. So as long as I am alive, I will take care of it,” he said. Subero, who can trace his family back to Venezuela, then declared that he was the former bandleader of the Naya Sangeet Orchestra of Brothers Road, and sang for us an Indian classical composition. The Express found some of Eddie’s relatives in Pleasantville, San Fernando. They remembered a proud man with a photographic memory. He was also a stick fighter, cricketer, had a passport but never left Trinidad, and got a driver’s permit but never owned a car. What he loved most, they said, was telling stories about his time as a railway man and was disappointing that his knowledge and name never became part of the public record. Now they are. (Source: Daily Express, Feb 16, 2022) • Note: Richard Charan can be contacted at [email protected].

0 Comments

Leave a Reply. |

T&T news blogThe intent of this blog is to bring some news from home and other fun items. If you enjoy what you read, please leave us a comment.. Archives

July 2025

Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed