|

Caribbean model, Gabriela Bernard, is forced to chemically relax her hair to avoid elimination in a reality TV show

0 Comments

Here are some interesting cleaning hacks. Click on the link here

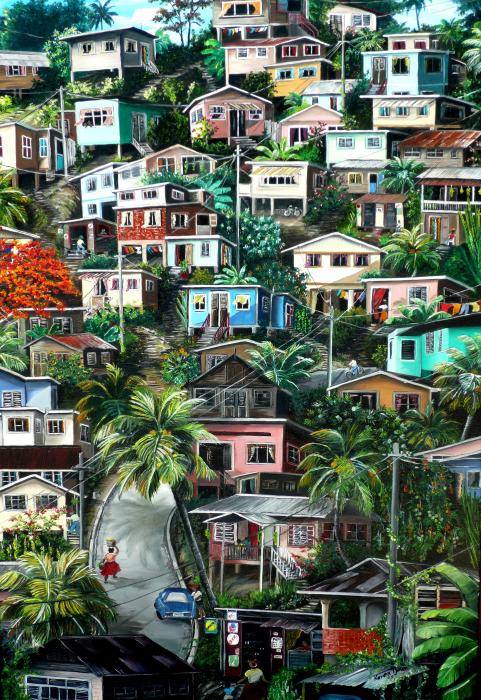

The Word "Laventille" is actually French. Its derived from "La Ventaille", which means The Vent..Its named so because of the winds that passes through..Here's an exotic painting of the hills.

Trinidad and Tobago has been known to experience tremors and earthquakes due to its location along the southern border of the Caribbean Plate.

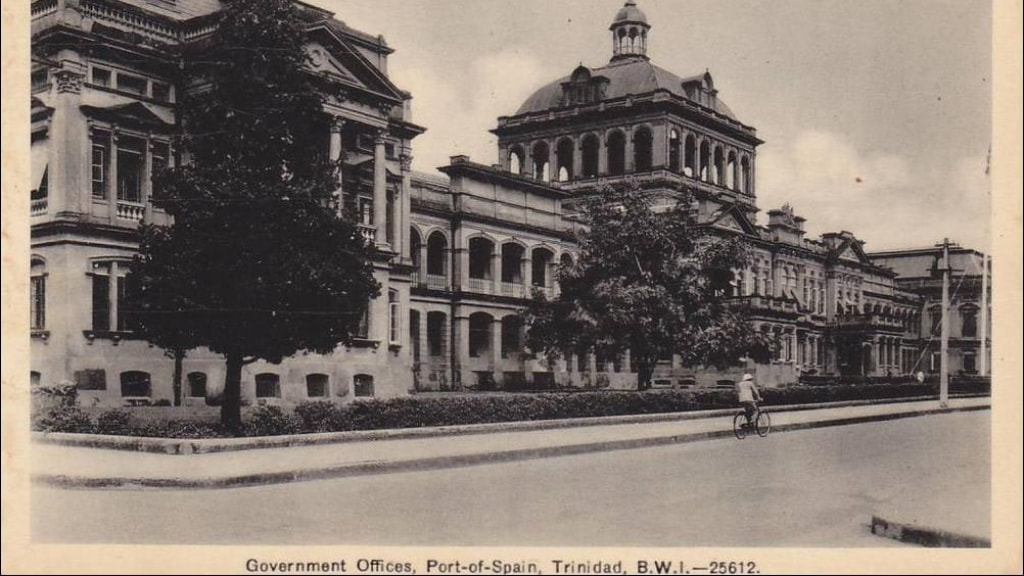

On August 21, 2018, a 6.9 earthquake caused massive panic, terror and confusion as citizens reported houses shaking, items falling off supermarket shelves and cracks forming in walls and along the ground. The earthquake measured an earth-shaking 6.9 and was felt in both Trinidad and Tobago, as far north as Grenada and as far south as Guyana. The epicentre of the 'quake, which was recorded in Venezuela, registered a magnitude of 7.3 on the Richter Scale. The US Geological Survey said this was the largest historic event within 250 kilometres of this location in the 20th and 21st centuries. Here’s a look at some of the worst earthquakes to hit T&T: 1. 1766 – San Jose The catastrophic earthquake of 1766 destroyed Trinidad's original capital of San Jose, now known as St Joseph, by a 7.9 earthquake, which may have been a factor in relocating the capital to Port-of-Spain. 2. 1888 Records show a 7.5 earthquake occurred within the Caribbean region, causing damage from Trinidad to St. Vincent. 3. 1954 - Trinidad Another strong earthquake was reported in 1954, with a magnitude of 6.5. A newspaper clipping titled ‘Earthquake in Trinidad’ in Australia’s Cairns Post was more concerned, however, that it spoiled the impending visit of Princess Margaret: “Trinidad, correspondent says that the earthquake yesterday seriously damaged the room in Government House which Princess Margaret is to use on her visit early next year.” The report added that “Heavy slabs of fallen masonry were piled high in the passage between the Princess' living room suite and the bathroom. The rooms were recently re-decorated in readiness for her arrival and will now have to be repaired.” “Glass lampshades were shattered and hardly a room in Government House does not show cracks, caused by the tremor, which was the worst in living memory,” the report said. 4. 1968 In 1968 a 7.0 earthquake was reported to have occurred near Trinidad, causing significant damage to neighbouring Venezuela with some damage to Port of Spain. 5. 1982, Tobago A 5.2 earthquake struck Tobago, which was the largest earthquake to occur up to that time. 6. 1996 – Trinidad, New Year’s Day A 5.2 was recorded as occurring just north of Trinidad on New Year’s Day. Luckily, there were no reported injuries. 7. 1997 – Tobago The 6.1 earthquake which occurred in 1997 caused major damage with an estimated US$25 million in damages occurring in Tobago, causing two persons to be injured and leaving 15 people homeless. 8. 2006 – Trinidad The country was rocked by a 5.8 earthquake in 2006, according to a Newsday report. No lives were lost, however some damage was reported and there were some injuries reported. 9. 2007 - Martinique, felt in T&T According to the Office of Disaster Preparedness and Management (ODPM) a massive 7.3 earthquake occurred near Martinique but it was felt throughout the Eastern Caribbean from Puerto Rico to Guyana, including T&T, with damage reported in Martinique, St. Lucia, St. Vincent and Barbados. 10. 2013 - Trinidad A massive 6.4 earthquake reportedly occurred just 74 kilometres north-west of Port-of-Spain on October 11, 2013, the strongest to occur since the ‘quake of 1997. Here are some helpful earthquake terms:

Here are 5 safety tips if an earthquake occurs:

Stay safe! Former U.S. President Barack Obama has recommended 'A House for Mr Biswas' by the late Trinidad and Tobago-born writer, Sir VS Naipaul, as one of five books for reading over the summer period.

In a Facebook post on Sunday, Obama wrote: "One of my favorite parts of summer is deciding what to read when things slow down just a bit, whether it's on a vacation with family or just a quiet afternoon. This summer I've been absorbed by new novels, revisited an old classic, and reaffirmed my faith in our ability to move forward together when we seek the truth." During his eight years in the White House, Obama turned to books to find balance, "slow down and get perspective." With regards to Naipaul's book, he wrote: "With the recent passing of V.S. Naipaul, I reread 'A House for Mr Biswas,' the Nobel Prize winner's first great novel about growing up in Trinidad and the challenge of post-colonial identity." The book was one of many in which Naipaul explored the cultural elements he felt tied to as a man of Indian ancestry, born in Trinidad and raised in England. The other four books on Obama's list are "Warlight" by Michael Ondaatje, "Educated" by Tara Westover, "An American Marriage" by Tayari Jones and "Factfulness" by Hans Rosling. Source: CNC3  Port-of-Spain has quite a compelling history, with nuances and facets that we see every day without actually knowing their origins. Before the Twin Towers, there was Freetown. Before the International Waterfront, there was Puerto d’España, a port kept under wraps from pirates and enemies of the Spanish. The city of Port-of-Spain is 104 years old and for the month of June, the Port-of-Spain City Corporation will be hosting a number of events to celebrate this anniversary. To help commemorate, we dug up some pretty interesting facts about the nation's capital. Here are 10 facts about the city you probably didn't know. 1. Belmont was previously called Freetown The British abolished the slave trade in 1807 but the British Royal Navy were ordered to patrol the African West Coast and prevent the illegal transportation of slaves by British ships. As a result, a number of Africans were freed and some of them were brought to Trinidad. Coming from tribes including Yoruba, Rada, Mandingo, Ibo, and Krumen, they were brought here, not as slaves, but as free men and given land in Belmont. Belmont became known as Freetown for a while, extending from the East Dry River at the north end of Circular Road, and up into the Belmont Valley Road. 2. Before there was St. Ann’s, there was Belmont Asylum The Belmont Asylum was founded in 1851 and was located on Circular Road, opposite to where the secondary school is today. It was eventually moved to St. Ann’s and became known as the ‘Mental Hospital’. 3. The capital was intentionally kept uninhabited at one point Under Spanish rule in the mid-16th century, Trinidad was a strategic outpost to the Orinoco delta. In an attempt to avoid drawing the attention of pirates and other Spanish enemies, the Spaniards kept Trinidad unpopulated, keeping the island as just a port to keep Spanish ships safe in the Gulf of Paria. They spread rumours that Trinidad was dangerous and was a catchment for diseases like yellow fever and malaria. The main anchoring place didn’t even receive a proper name but was just called a ‘Harbour of Spain’ or Puerto d’España. 4. The 'jamette society' originated in Port in Spain At one point, the streets of east Port-of-Spain were known as the ‘French Shores’, and those who inhabited them were known as jamettes (from French ‘diamètre’). The term referred to those outside the circle (the ‘diameter’) of polite society. In the eyes of the colonial government, the jamette society was outrageous, vulgar and obscene. 5. Everyone and everything was thrown in prison The Royal Gaol on upper Frederick Street was completed in 1812 where criminals, along with debtors, the insane, and even animals were thrown into it. 6. Governor Woodfood passed an interesting law to protect the streets of Port-of-Spain After he became Governor in 1813, Sir Ralph Woodford was keen on modernising the face of Port-of-Spain. Sidewalks were constructed and paved with gravel. To preserve the new (and expensive) streets, a law was passed in 1824 forbidding the keeping of pigs in the city. Additionally, cows, goats, horses, and mules had to be kept in compounds and were not allowed to roam the streets anymore. 7. The first boys' school opened in 1823 The first primary school for boys was opened in Port-of-Spain in April 1823 followed by a primary school for girls in 1826. 8. Queen's Park Savannah was initially intended for cattle Governor Woodford purchased Paradise estate in 1819 from the Peschier family. The area, originally called 'The Savannah' was cleared ‘for the recreation of the townsfolk and for the pasturage of cattle’. It was later officially changed to 'The Queen's Park Savannah' in 1845. 9. The Botanic Gardens had Far East influences The Governor bought additional land from the Peschier estate at St. Anns, which was constructed for the new Government House and the Botanic Gardens. Botanist David Lockhart was hired to design the Botanic gardens; he introduced many trees from the Far East into Trinidad, the most notable being samaan tree. 10. The Queen's Park Savannah was used for many sporting events In addition to being an open pasture, the Savannah provided the residents of the town with their first golf course and the game was played with the grazing cows and running horses. Horse-racing was also introduced in 1828; by 1854, after the erection of the Grand Stand, horse racing was held annually. The Savannah was quite the multipurpose venue, with cricket, polo, football and other sports taking place in the open space. Source: The Loop  Mareena Robinson Snowden, is the first Black woman to graduate from MIT with a Ph.D. in Nuclear Engineering Black girl magic was in full effect earlier this month when Mareena Robinson Snowden, became the first black woman to earn a Ph.D. from MIT in Nuclear Engineering. Snowden’s dissertation focused on the development of radiation detectors for future nuclear arms control treaties. According to her personal website, she is a native of Miami and earned a B.S. in Physics from the illustrious Florida A&M University. Snowden took to her Instagram to share some of her thoughts on her achievement:“No one can tell me God isn’t. Grateful is the best word I have to describe how I feel. Grateful for every part of this experience – highs and lows. Every person who supported me and those who didn’t. Grateful for a praying family, a husband who took on this challenge as his own, sisters who reminded me at every stage how powerful I am, friends who inspired me to fight harder. Grateful for the professors who fought for and against me. Every experience on this journey was necessary, and I’m better for it.” She went on to shout-out a few Black women who’re also displaying Black girl magic. “When they ask where the skilled black female technical minds are, know there are many – @joymariejohnson, @_sai_89, @rhondalenai, @being_niaja, @jtiaphd, @siangoan, April Gillens, @beyoncizzle, Tiera Fletcher, Ciara Sivels, Grey Batie, @tashaleeb, @special_kay868, Staci Brown, Njema Fraizer, @jedidahislerphd, Delonia Wiggins, Jami Valentine Miller and many more – who show up proudly in the fullness of their black womanhood and fight each day for our place in these fields.” Thank you Mareena Robinson Snowden, Ph.D. for all your hard work and dedication we look forward to seeing all the amazing things you will accomplish next! Source: The Black Detour2018 a trini is the mastermind behind the flat panel display touch screen....did you know? I didn't.6/26/2018  When next you watch a flat screen TV or the slim screen on your laptop, thank Trinidadian research engineer Dr. Andre Dominic Cropper. He is the mastermind behind the Flat Panel Display Touch Screen made from thin layers of laboratory produced diamond called Organic Light Emitting Diode (OLED). Cropper’s US patent for a new Organic Light Emitting Diode (OLED) facilitated the development of flat panel displays, which are today used in most electronic devices from ATM machines and flat-screen TVs to laptop computers. He holds two patents for the inexpensive manufacture of OLEDs for use in TV displays. Born on August 4th 1961, Cropper grew up in St. James and attended Newtown Boys’ RC School as well as Fatima College. He had a keen interest in electronics from an early age, and his schoolboy hobby was dismantling and reassembling electronic devices. He was also a keen swimmer at Flying Fish Swimming Pool, and went on to represent Trinidad and Tobago on swimming teams in regional and international games during the 1970s. He, however, declined joining the T&T swim team to the 1984 Olympics in order to complete his university education. He had already gone to the United States in 1978 and, at the time, had just graduated with a Bachelor’s degree in Electrical Engineering at Howard University in Washington D.C., but immediately started his Master’s degree. He graduated with honours in 1987. Upon graduation, Cropper began teaching at Norfolk State University in Virginia. In his spare time, he began research on diamond technologies, and the use of thin layers of laboratory-developed diamonds as a semiconductor for new technological applications. Cropper sent a proposal of this work to NASA, which was impressed by the idea. But, since he did not have his Ph.D., NASA stipulated that he would have to hand over his research to “a qualified researcher” and work under that person. Cropper refused the offer and decided to pursue a doctoral degree and develop his idea. In 1995 he obtained his Ph.D. in Electrical/Materials Engineering from Virginia Polytechnic Institute and State University in Blacksburg, Virginia. On completion of this doctorate, he returned to Trinidas where he began teaching at the University of the West Indies in the Department of Electrical Engineering. In 1999, Cropper joined Eastman Kodak Company in Rochester, New York, as a Research Associate and Project Manager of OLED applications. His research work at Kodak included OLED applications, thin film diamond growth, production and its novel applications, new semi-conducting electronic and optoelectronic materials, flat panel display technologies, remote sensing, image exploitation and compression, information extraction and motion estimation. His eventually took the position of Technology Development Manager for the Sensor Products within ITT Industries Space Systems Division. In 2005 T&T recognised Dr. Cropper with the “National ICONS in Science & Technology” Award, and in 2006 the “Caribbean ICONS in Science Technology & Innovation” Award. Also in 2006, Rochester Museum and Science Center, in Rochester NY, honoured him as one of the “Inventors – Who Makes Things Work in Rochester”. In 2014, he was the recipient of the “Professional of the Year” Award for outstanding career achievements, from American Indian Science & Engineering Society (AISES), and from Raytheon the “STAR Award” for outstanding Achievements within STEM Community in 2014, as well as an “Inventor Award” in 2014 and 2015. This Caribbean icon in innovation embraces the arts, believing there's a similarity between artists, engineers and scientists - they create new things. In a video feature by NIHERST, published on YouTube in 2012, he says: "An artist creates something...brings new experiences to life. A scientist does the same thing - brings a new technology forward, creates something new. There's a lot of synergy between arts and science." Dr. Cropper is married to Trinidadian Natalie Rogers-Cropper, a professional dancer and dance school administrator at Garth Fagan Dance Company. Source: www.caribbean-icons.org Another Trini making news - check it out here

This was brought to my attention by yet another Trini author, Anne Marie Meyers, living and working in Toronto. Here is what she had to say: "Remember the interview I did back in February 2017 about a young girl and her mother creating a magazine called 'Contagious'? with the aim of writing articles featuring positive accomplishments by kids? Well their magazine has gone national, and guess what, they are from Trinidad. Feeling proud here. This is the link to the interview and below you will see them being interviewed on television. . |

T&T news blogThe intent of this blog is to bring some news from home and other fun items. If you enjoy what you read, please leave us a comment.. Archives

June 2025

Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed