|

From the blog of Patricia Bissessarsingh Feb 22 2024.

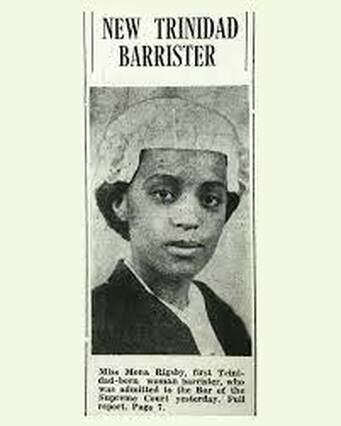

Women's History Month is the perfect time to reflect on some of our lesser-known heroines out there. Women who are not household names , but women everyone should know about because of their incredible contributions in different field of endeavours. Today’s blog shines the spotlight of attention on; The first Woman Lawyer to be admitted to the Bar in Trinidad Did you know that women were not allowed to practice in the Courts of Trinidad and Tobago until well over a hundred years after our first Civil High Courts were established in 1822? In 1939, Mona Marjorie Rigsby became the first Trinidad and Tobago-born female attorney-at-law to be admitted to practise in the local Courts and the youngest barrister across the British Empire. Ms. Rigsby was born in Port of Spain in 1918 and in 1935, she wrote and passed the entrance examination for London University. She then attended Middle Hall, where she secured honours in the fields of Roman Law and Criminal Law and Procedure. She was called to the Bar in England in June 1939 at the age of twenty-one. At that time, upon her call, she was the youngest barrister, male or female, across the entire British Empire. Ms. Rigsby returned to Trinidad and Tobago and was admitted to practice in the local Courts in September 1939. Mona Marjorie Rigsby and other women barrister like her not only paved the way for women in enter the male dominated legal fraternity but they also deserve our respect, admiration and remembrance. TRIVIA QUESTION Who was the First female judge in Trinidad and Tobago ? Credit to the following sources : · Mona Marjorie Rigsby: Photo courtesy of the Trinidad & Tobago Guardian published on September 6, 1939, which is part of the National Archives of Trinidad and Tobago Newspaper https://www.facebook.com/nationalarchivestt/photos · https://civilwatch.wordpress.com/2021/08/02/who-were-the-first-women-to-practise-in-the-courts-of-trinidad

0 Comments

TT Culture and the Arts e-book cover. AN e-book version has been created for the book Celebrating Trinidad and Tobago's Culture and Arts, making it freely accessible globally.

Author Nasser Khan expressed his gratitude to Minister of Tourism Randall Mitchell and his staff for backing the initiative. Described as the Students Companion of TT Culture and the Arts, over 600 educational institutions received approximately 2,000 hard copies of the 336-page book back in 2019. Researched and written by Khan, his 30th publication inclusive of the e-book, the book contains 33 chapters on topics including Carnival, literary arts, religious festivals, culinary arts and music. There is a special chapter entitled Uniquely Tobago, a media release said. Khan had lamented back in 2019, "Currently in the schools of TT there is no one reference book specific to the broad spectrum of our culture and the arts. Students and teachers must therefore use a variety of resources for assignments…I wanted this book to be a one-stop shop to reduce the amount of time it takes for people to consult multiple sources on the history and culture of TT, depending on the scope of their research.” Then minister of culture Nyan Gadsby-Dolly said, "The very title of this book, Celebrating TT's Culture and Arts, speaks to the importance of what this book brings to our young people." She said it is important for people to recognise the country's rich culture and develop a greater sense of patriotism. The book covers all of TT's cultural and artistic forms of expressions, with illustrations. The online link is: https://archive.org/details/cultureandthearts.com THE STORY OF A LOCAL HISTORIAN WHO NOT ONLY USED WORDS BUT HAND EMBROIDERED CREATIONS TO DOCUMENT HISTORY OF HER FAMILY’S ISLAND RESORT. Blog by Patricia Bissessar

At the Angelo Heritage House in Belmont , in the room designated the Sewing Room adorning one of the walls are two antique linen cross stitch samplers from Barbados, embroidered by sisters Hannah and Barbara Monteith in 1804. Aside from being unique to the region (cloth does not survive well in tropical weather) they are poignant and simple in their execution and showcase the needle work skills of these two sisters that time has long forgotten. For as long as women have been sewing, they've been using embroidery to tell their own stories. History lives on in their stories. This blog ‘A Stitch in Time” is a story of one of our local historians and author of the book Voices in the Street, Olga Mavrogordato née Boos who used embroidery stitches and techniques to create family heirlooms that captured memories pertaining to distinguished guests who spent time at the Boos family resort on Huevos Island. For those unfamiliar with Trinidad , Huevos is the second island out from Trinidad’s mainland in the Bocas Islands of the Dragon’s Mouth, which protects the Northern end of the Bay of Paria. It lies west of Monos, and east of Chacachacare. Huevos island is owned by the Boos family where once upon a time was visited by royalties and other distinguished guests seeking a holiday escape to a private paradise island in the Caribbean Our story is about a member of the Boos family, OlgaJohanna Mavrogordato née Boos who was born in Trinidad. OlgaMavrogordato née Boos, was one of the remarkable archivists and historians of Trinidadand Tobago. She described herself “as a creole born in the early 1900s” and claimed that her family’s oral tradition, a sort of collective memory, of most of the nineteenth century served as an inspiration to ignite the spark and passion in her for learning more about and documenting our local history “Long ago“,according to Geoffrey Mac Lean had this to say when asked what ignited her passion and interest in our local history “ “our parents told us stories of the past, either about our family or the places they knew and the things they did when they were young …… there was time then to sit around and listen, but the pace of life has changed and today our young people, caught up in a jet age, with the vital present and bright future, have no time to look back at the past, or even to wonder about it.” Mavrogordato accumulated in her lifetime accumulated an extensive collection of historical documents, photographs and rare books, wrote numerous historical papers, but what many people do not know about her was that she was a skilled embroiderer who enjoyed using thread and needles to create works of art using linen fabric as her canvas as much as she did writing and documenting our local history. She used her needle craft skills to create not only artistic work of art but heirloom pieces that would one day serve as a reminder of Huevos island’s glamorous and exciting history. De Verteuil C.S .Sp ( 2002) in his book Western isles of Trinidad mentioned that Olga’s passion for needle craft began in her younger days when she would use cross stitch and embroidery to create beautiful messages enhanced with embroidery scenes . These works of art, using needle and thread as her artistic tools were then framed and hung in the living room of the Boos’ family. De Vermeil also makes mention of the fact that when Olga served as hostess to the Boos’ Family Resort on Nuevo’s Island invited guests who spent time at the resort when leaving would be invited to sign their autographs on a hand embroidered linen table cloth Olga had made which featured an embroidered map of the island of Huevos. Olga , however , being the historian that she was , when her guests left would erase the signatures of those guests she deemed “ camp followers” , keeping only those of the more distinguished guests which she immortalized on her table cloth using the art of cross stitching. Some of these guests included: The Duke and Duchess of Kent (1935), Sir Anthony Eden (British Prime Minister 1955-57) (1959), Princess Margaret and Lord Hailes (to inaugurate the Federation of the W.I. in 1958), Princess Royal (1960), Princess Margaret and her husband on their honey-moon (1960) and Lord Mountbatten of Burma (1965). According to De Verteuil ( 2002) , when this hand embroidered tablecloth was filled with the signatures of these VIP guests , Olga began work on a new linen tablecloth which featured embroidered maps of Chacacharare , Monos as well as Huevos. As with the first , the second tablecloth was soon filled with signatures of distinguished guests at Huevos and was designed to serve as a means of preserving history of the lavish hospitality of the Boos family at their island Paradise. Olga Mavrogordato was indeed remarkablewoman . Her artistic creations not only explored the interplay between map images and text, without privileging one over the other but her hand-embroidered pieces told a story with each stitch that was created of Huevos Island’s glamorous and exciting past. If telling stories is what makes us Human, maybe the time has come for today’s youths to find innovative ways of telling a new story, one stitch at a time .As Betsy Greers, founder of Craftivists (2003) wrote : “We are the makers of our own future. We are the crafters of calmer minds. Our stitches are strength. And hope. And love. For strangers, for loved ones, and most importantly, for ourselves. Because without crafting our best selves, we are less use to others.” Credit to the following sources Western Isles of Trinidad ,De Verteuil, Anthony .Published by Paria Publishing Company Ltd., 2011 Geoffrey Mac Lean citizensforconservationtt.org: Olga Mavrogordato’s Voices in the Street.  Due credit to Dhaneshar Maharaj who is author of the following blog TRIP DOWN MEMORY LANE LANDMARK IN SAN FERNANDO. ALLOY SHOP The photo depicts a site on SUTTON STREET, with FREELING STREET to the east (left) and IRVING STREET to the west (right). The building seen in the “THEN” photo was what we called “ALLOY SHOP”, a business operated by a Chinese proprietor from the 1940s to the early 1970s. Grocery items were sold on the left side while the right side had a parlour where you could buy something to eat and drink and there was even a small wooden table to sit at by the window and look outside at the occasional vehicle passing or admire the greenery in Irving Park, looking northwards. My favourite meal bought at Alloy’s shop was a six cents loaf filled with butter and cheese (oily and a bit rancid at times) and a Nestlé chocolate milk in a glass returnable bottle, to wash down the bread and cheese. When funds were a little scarce, I would settle for a plain bun or coconut drops and a banana SOLO. Food items were kept in a glass case on top of which sat a cat or two and these would have to be chased away from the glass case when Alloy’s wife was making a sandwich or selling drops, buns, biscuit cake or bellyful cake. The cats were probably kept in order to keep away the mice which roamed the shop and parlour in the night and nested amidst the many spaces and holes in the old, warped wooden floor of the shop. This was the closest shop to where we lived and I remember being sent very often when my mother was cooking, to buy a pack of curry (a penny a pack) or a pound of salt (cent a pound) and probably buying a cent Paradise Plum (three for a cent) or a ‘sours’ with part of the change. It would take me just about thirty seconds to run uphill from my house to Alloy shop to get these items. Children never walked in those days when going on errands. We would run at top speed since we had no shoes or slippers to wear at home and would try to minimize the time the soles of our feet came into contact with the hot asphalt as we went barefooted about our errands. We would fall occasionally when running and grate away parts of the skin on our arms and legs, but we were healthy kids and these bruises and scrapes soon healed without the aid of medication, not even leaving scars on our skins. When Alloy died, his family ran the business for a while but then it was sold to an East Indian man who had a blue Opel motor car and who operated a garage in the back. This new owner kept the place enclosed day and night so no one was able to see inside the premises, except when he was reversing his car out of the garage on to Irving Street and would open the galvanize gate to do so. Once I saw a woman sitting in a hammock, while the gates were open, and I would hear the occasional crying of little children coming from the enclosed premises as I passed by. Little or no renovation was done to this building for the many years in which this garage man lived here. The right side of the photo shows how the spot looks now. The photo was taken early on the morning of January 19, 2014. After the old wooden building was demolished, the spot stood vacant for some time. There was a short mango tree on the compound and grasses and weeds occupied the ground area. I am not sure, but I heard that the owner of Affan’s Bakery bought this spot along with the spot opposite on which the old TICFA building where WASA’s office was once located, and which has since been demolished. The mango tree has been cut down and the area fenced around some time last year and the ground paved over with oil sand. A doubles vendor now operates here out of a new truck, the tray of which has been modified to provide a mini kitchen for cooking bara, aloo pies, saheena and pholourie on the spot. (Just a passing observation. I have seen many doubles vendors with several vehicles, all of them fairly new and not of the cheap run of the mill type. Which tends to signify that a well-run doubles business can move one fairly high up the economic ladder). This doubles vendor sells from Tuesday to Sunday, taking a rest on Mondays. The business was run by a father-daughter combination, the father doing the bagging and money collection while the daughter was part of a team of cooks preparing the items for sale. I have not seen the father in recent times and the daughter has now taken over the father’s former role of bagging and cashing, though today, when I took this photo, there was a strange gentleman cashing and bagging stuff for customers. I first discovered this doubles team on a vacant car park lot opposite the SSL main building lower down on Sutton Street, i.e., at Gomez Street corner. They operated here for a long while until CHRIS BHAGWAT, the owner of SSL did some improvement on the empty lot and began to use it as a car park for his business and to store lots of iron and pipe stuff. Chris himself would patronize this vendor on a regular basis, especially on Sundays and despite his regular diet of oil, flour and other starchy stuff has remained quite lean, not an ounce of fat showing on his slender frame. This doubles business changed location to the pavement of the old, abandoned TICFA building (part of which is seen in the “THEN” photo) next to Affan’s Bakery, just opposite to where they are located today. I taught the owner of Affan’s Bakery (he is the son-in-law of the original founder and owner of Affan’s Bakery, so he is not an Affan, but is married to Affan’s daughter) while I was a young teacher at Naparima College, and I taught his son when I was a much older teacher at Presentation College. I would meet this bakery owner (forgot his name now) on Sunday mornings patronizing this doubles vendor who operated right next to his bakery. I discovered on one such Sunday, that he would buy a Sunday breakfast of doubles for his entire staff of Bakery workers and himself, probably giving this vendor the biggest sale for the day. During the spate of kidnappings plaguing the country about ten years ago, the bakery owner feared for his family’s safety and took his children out of school and along with his wife, sent them to live in Vancouver, Canada, where they now reside. After the old TICFA building was demolished last year the doubles vendor moved over the road to the former Alloy Shop site and has remained there to the present time. Items worth noting in this picture are the wrapper and money collector having to stand on a bench to be at a high enough level to function properly, a green plastic chair for lazy customers to sit on and eat in the shade cast by the truck, two coolers for supplying drinks to patrons eating on the spot, a garbage bin for the exceptional customer who knows how to use it or just feels like not littering on certain occasions, a water container some distance away to the east for washing hands, a fat customer wearing a number 8 jersey to indicate that he regularly consumes 8 doubles at a time and a number of pigeons which walk around to feed on any tidbits or morsels coming their way, sometimes from sloppy eaters who allow channa to fall out of their doubles or even let a whole doubles slip out of their greasy hands. And as I end let me remind you that the primary purpose of education is not to teach you to earn your doubles, saheena, pholourie and kurma, but to make every mouthful sweeter. (Source: Angelo Bissessarsingh's virtual museum of Trinidad and Tobago, Jan 10, 2024) Cocoa: Worth its weight in silver Angelo Bissessarsingh (Researcher and writer)

January 5, 2014 One of the great agricultural potentials of Trinidad is its ability to produce cocoa of the highest quality. But in a land which formerly led the world in production of the golden bean, the industry has dwindled to near oblivion. This column is the first of a three-part series which will take a historical look at cocoa and how it once drove the local economy. Cacao (Theobroma cacao) is the name given to a tree which was known to Meso-American peoples such as the Aztecs, Olmecs and Mayans for thousands of years before the arrival of Europeans. The Mayans believed that chocolate was a food from the gods, given to them by the Feathered Serpent, Quetzalcoatl. Christopher Columbus encountered the beans in 1502, as did Hernan Cortes, who dominated the Aztecs in the Yucatan. Cortes and his conquistadores were served a bitter, hot beverage spiced with pepper and little resembling the stuff we call chocolate today. Cocoa seems to have been introduced in Trinidad in the 17th century, since it was one of the few cash crops cultivated for export by the Spanish settlers. It was also grown by subjugated Amerindians on the missions established by Capuchin monks from 1687-90. Cocoa constituted almost the only export of the colony and was much in demand in Europe—especially in France, where chocolate drinking was becoming vogue. Cocoa was worth its weight in silver, so that one morning in 1716, the frightened residents of Puerta de los Hispanoles (Port-of-Spain) saw an armed sloop sweep in and seize upon a brig loaded with cocoa bound for Spain. The pirate ship belonged to the notorious Benjamin Hornigold, an American buccaneer, and it was under the command of a young protégé of his named Edward Teach, who would later terrorise the high seas as Blackbeard. In 1725 witchbroom disease struck the cocoa plantations and this was seen by some as a divine punishment because the planters had not been paying their tithes. The island’s economy grew exponentially at the end of the 1700s as the introduction of the Cedula of Population encouraged (mostly French) Catholic planters and their slaves to emigrate and thus much arable land was brought under cultivation. Most of this was sugar, but in the hills of the Northern Range—particularly in Santa Cruz, Maracas Valley and Diego Martin—the cool climate and well-drained soils were perfect for cocoa cultivation. After the capture of Trinidad by the British in 1797, sugar somewhat outstripped cocoa as English capitalists began to acquire lands, but there remained enough of the cacao trees in the Santa Cruz valley to enchant Henry Nelson Coleridge, who exulted in 1825: “If ever I turn planter, as I have often had thoughts of doing, I shall buy a cacao plantation in Trinidad. The cane is, no doubt, a noble plant, and perhaps crop time presents a more lively and interesting scene than harvest in England! The trouble of preparing this article for exportation is actually nothing when compared with the process of making sugar. But the main and essential difference is, that the whole cultivation and manufacture of cacao is carried on in the shade. People must come between Cancer and Capricorn to understand this. I was well tired when we got back to Antonio’s house. What a pleasant breakfast we had, and what a cup of chocolate they gave me by way of a beginning! So pure, so genuine, with such a divine aroma exhaling from it! Mercy on me! What a soul-stifling compost of brown sugar, powdered brick, and rhubarb have I not swallowed in England instead of the light and exquisite cacao!” And, of course, no cocoa plantation would be complete without a dash of vermilion, as Captain Alexander recounted in 1833: “One of the most beautiful of the trees in Trinidad, is the Bois immortel, which at certain seasons of the year is covered with clusters of scarlet blossoms of exceeding brightness, and which when shining in the sunbeams, look like a mantle of brilliant velvet. “The tree is very lofty and umbrageous, and serves as a screen to the cocoa plant, which being of too delicate a nature to bear exposure to the sun, is always planted under the shelter of the Bois immortel. This double wood has a very pleasing effect, especially when the cocoa is bearing fruit, when its various colours are beautiful.” Cocoa estate buildings .Photo Credit : Scott He (Source: Angelo Bissessarsingh's Virtual Museum of Trinidad & Tobago, January 5, 2024) Author :Angelo Bissessarsingh

Christmas just ain't Christmas without a good ham. In Trinidad of yesteryear, the precious leg of pork would be boiling in a pitch-oil tin for many hours before being baked, either in a coalpot tin oven or a beehive mud oven, to be served with other traditional fare like pastelles and fruit cake. Chances are the ham would be diminished long before the family could have a go at it, through the inroads of "moppers," otherwise known as village paranderos. The choices for ham lovers were not easy. Price was a major consideration as well as quality. In the countryside areas, the ham everyone knew was a salty, well-cured leg of pork hanging from the rafters of the Chinese shop. This would be an American ham, imported in barrels of sawdust with some of that still clinging to the surface. After boiling the skin would be stripped off before baking. The skin itself was kept until after Christmas, when money was scarce, and would be used to provide protein in a meal of rice or as the meat in a sandwich. It could also be fried crisp and eaten as a snack. The fat was used to leaven bakes. Even the ham bone did not go to waste. Broken up in pieces, it was used in soups, callaloo and oil-down. The lowest grade of ham was what was known as the "pitch ham." This was locally made and smoked. To preserve it, the pitch ham had a coating of asphalt on the outside, which made the skin inedible and imparted a mineral flavour to the meat which I am told was far from unpleasant-although one can imagine that it was not the healthiest food around. In the early 20th century, an American ham cost about $5, with the pitch ham selling for $2 less. This was no mean expenditure in an era when it was a decent monthly wage for a domestic servant, making the ham an indulgence. The ham most Trinis were familiar with was the York ham. The York ham is mildly flavoured, lightly smoked and dry-cured, which is saltier but milder in flavour than other European dry-cured ham. It has delicate pink meat and does not need further cooking before eating. It is traditionally served with Madeira sauce. Folklore has it that the oak used for construction for York Minster in England provided the fuel for smoking the meat. York hams were sold from most city groceries like Cannings and the Ice House and also department stores with provision departments, like Stephens. The famous Ice House Grocery on Marine (Independence) Square included a York ham in its famous $5 Christmas hampers. Packed chock-full of goodies like Muscatel wine, nuts, imported sweets and dried fruits for the famous rum cake, these hampers could be packed into a wooden box and forwarded by rail to customers deep in the countryside. Even though some prefer turkey, the hallmark of Christmas is still a ham. Photo 1. : Salt ham hanging at Sing Chong Supermarket on Charlotte Street, Port of-Spain. Photo Credit : BRIAN NG FATT. (Source: Angelo Bissessarsingh's Virtual Museum of Trinidad & Tobago, Nov 27, 2023) By HISTORIAN AND AUTHOR ANGELO BISSESSARSINGH (2010)

For most Trinidadians, no Christmas season would be complete without a trip to Frederick St in Port of Spain to take advantage of bargains, window-shop and to savour the whirl and rush of humanity occasioned by the hectic Christmas atmosphere. This photo dates from 1950. With the jolly season now in full swing, we begin to be aware of those annual occurrences which make Christmas in Trinidad a unique and savory experience. The hams have begun to put in appearances in the supermarket freezers, and the ruddy hue of sorrel on the wooden trestles of roadside hucksters. Demijohns of ginger ale have begun to grace windowsills for fermentation, and notwithstanding the astronomical price of the raw material, most assuredly will give a sharp bite to those who dare to partake of the aged vintage. Errant bakers of the domestic kitchens are sampling with gusto the rum-drenched dried fruit which have been soaking since the middle of June and which will soon form an integral part of an aromatic fruit cake. Toys which range from the simple trinkets of a bygone era to complex mechanisms with embedded microchips have commenced their temptation of young desires who fervently hope that Santa will bestow upon them, the rewards of a year of good behavior. Amidst the thick air of anticipation and festivity it would not be amiss to take a retrospective look at local Christmases of yesteryear. Almost every nostalgic Trinidadian and Tobagonian can tell stories of the ham being boiled in a pitch-oil tin, the flurry of new curtains, paranderos and the joyous tedium of pastelles on the make, but I intend to take a more historically systematic view when looking at the Trini Christmases Past. In the pre-emancipation era (1834 and earlier) Christmas was celebrated in the plantation great houses with much pomp and ceremony as befitted the status of landed gentry. With the influx of French settlers with the 1783 Cedula of Population, Christmas balls became fairly commonplace, graced no doubt by lavish dinners of wild meat roasts, consommés of local fruit, and wines imported from Europe. The house slaves of the estates would have been the grateful end beneficiaries of the residue of these Christmas revels of the masters. The pleasure of the field slaves were infinitely more simple and consisted of little more than an extra allowance of food and perhaps a length of cloth. One account from 1823 tells of a Christmas on Lopinot’s La Reconnaissance cocoa estate where slaves were given a dole. The account runs thus ‘At nine o’clock while at breakfast, the whole of the negroes came dressed in the gayest clothes to wish us a Merry Christmas, and a piece of beef and an allowance of flour and raisins were distributed to all of them with a proportion of rum for the men and wine for the women.’ The writer continues to describe how the slaves were given two suits of clothes each, following which they visited the cemetery of the Lopinot family (still to be seen) where prayers were said for the departed Comte de Lopinot and flowers strewn over the huge unmarked gravestones. With the advent of East Indian labourers on the sugar and (to a lesser extent) cocoa estates of the island after 1845, Christmas took on a dimension of minor importance. Mostly, the labourers were Hindus and Muslims and therefore did not celebrate Christmas. Admittedly, some aspects of the field slave Christmas still survived as 19th century accounts tell of one proprietor’s wife in Central Trinidad, Elisa DeVerteuil, sharing out an annual bonus of flour, cloth and other staples to the East Indians of Woodford Lodge estate. The arrival of Rev. John Morton in 1868 marked the commencement of the Canadian Mission to the Indians (CMI) through the auspices of the Canadian Presbyterian Church. Under the influence to the early missionaries of the CMI, Christmas became a more regular occurrence in the predominantly Indo-Trinidadian sugar-belt communities of Central and South Trinidad. Those early CMI Christmases were simple affairs, with carols being sung (some in Hindi through the translations of the Rev. Dr. Kenneth Grant and Lal Behari) and presents in the form of decorated cards and booklets being distributed, these being sent from mission fields in Canada for the benefit of their ‘heathen’ brethren in Trinidad. Conversely, as is recorded by Sir V.S Naipaul in A House for Mr. Biswas, Indo-Trinidadian Christmas celebrations in the estate barracks comprised for the most part of a surfeit of food and grog, after which a spate of wife and child beatings would inevitably follow to cap off Christmas Day revelries. Christmas for the urban Afro-Trinidadian, particularly for those of the barrack-yards of East Port of Spain, was a more complex affair although like their East Indian contemporaries, Yuletide activities invariably involved the consumption of copious libations of spirits, sometimes with unwelcome side-effects. The seminal thesis on life in the barrack-yards published by James Cummings (Barrack-Yard Dwellers) gives an insightful window into the Christmases of these unique inner-city environments. Cummings tells of old curtains being boiled in a broth of tea-leaves to brighten the fading textiles, when new pieces could not be afforded. Crockery, which languished year-round as ornaments would be washed in anticipation of the Christmas feast, the preparation of which was a process in itself. According to Cummings, chicken, ham and beef would be prepared according to the circumstances of the families. ‘Professional’ women known as matadores, would be provided with money beforehand by their male ‘keepers’ and would indulge in much food and drink for the big day. The all important preparation of the fruit cake would be supervised by ‘peel men’ at local bakeries, which in fine Dickensian style, would take in the batter of the barrack-yard cakes to be baked. The peel men were sometimes tipsy from numerous shots of rum, so often the cakes met with disaster when being slipped into and out of the mud ovens with a long-handled wooden paddle known as the ‘peel’. The menfolk of the barrack-yards were not left standing in the Christmas bustle. Months beforehand, they would purchase gallons of poor-quality rum known as ‘ca-ca-poule’ to which would be added tonka beans, citrus peel and even methylated spirits to increase the mellowness and potency of the rum. A more dignified barrack-yard Xmas dinner of the 1930s is recounted in C.L.R James’ Minty Alley wherein the well-furnished table of Mrs. Rouse is graced by a quart of iced champagne, good company and the unique camaraderie of a truly Trini Christmas. A valuable glimpse of a Christmas of the white planter elite in 1911 is given by P.E.T O’Connor, whose grandfather, Gaston De Gannes was one of the last aristocratic French-Creole patriarchs of the plantation era and who presided over his stately home, La Chance, near Arima. Every Christmas, De Gannes’ large family would descend on La Chance, complete with a battery of maidservants for care of the children. O’Connor describes the Christmas morning ritual where the children were sent up to Gaston’s room to pay him their season’s compliments: ‘He would be standing in his bedroom near his huge wardrobe with its doors open, as on the inside was tacked a neatly written list of grandchildren. As we all paraded in and out with our good wishes, he would consult the list and hand out the appropriate largesse. A golden sovereign to the eldest son of each family, a half sovereign to the eldest girl and a silver crown or half-crown to the younger children’. In terms of the monetary values of the day, the golden sovereign coin was worth more than an entire year’s wages for one of the labourers on Gaston’s cocoa estates. O’Connor goes on to describe the breakfast of hot chocolate and bread, followed by Mass at Santa Rosa R.C Church, the day being crowned by a magnificent family dinner, graced by Bordeaux wine and French claret. The emergence of parang is really attributable to the influx of peons, called the panyols, of Venezuela, who provided a significant percentage of the labour force during the cocoa boom years of 1870-1920. While parang has become fairly commercialized of late, the Christmas ritual, introduced by the panyols, actually involves three stages. In Lopinot, the tradition held true for many years, preserved by such sages as Sotero Gomez and Pedro Segundo Dolabaille. The first stage is when upon arrival at a hospitable home, the paranderos would sing from the doorstep, an Aguinaldo, or song of praise, telling of the Nativity, Adoration or Ascension of Christ. This is the signal for the householder to throw open his/her doors to the paranderos who continue to serenade the home with Aguinaldos until the descanso, or rest period, when the bards are regaled with victuals and drink consisting mainly of ham, pastelles and fruit cake, as well as sorrel and ginger beer. From the doorsteps of the countryside, the parang music was taken to a national level by the artistry of pioneers like the late Parang Queen, Daisy Voisin and the Lara Brothers. While on the subject of music, it is interesting to note that in San Fernando during the 1870s to the 1890s, the crown jewel of the town’s Christmas events calendar consisted of a grand concert which was held first at the Oriental Hall on Carib St. (present-day location of Grant Memorial Presbyterian School) and later, at the Drill Hall (where Naparima Bowl now stands). The performers in this cantata almost unanimously hailed from the very musically-inclined Vilain family, who were a prominent coloured French Creole clan. Patriarch Jean-Marie Vilain, along with his sons Pierre, Alexander and Jean-Marie Jr. were gifted musicians. Pierre, until his death in 1879, even had an international reputation as a master of the violin which earned him the title of ‘The West Indian Paganini’. With the death of Jean Marie and Alexander in the 1890s, this chapter of San Fernando’s Christmas story was brought to a close. In retrospect, Christmas has from the earliest period, occupied a special place in the collective consciousness of our people. Even when adversity beset the islands during two World Wars and the recessionary period of the 1980s, nothing seemed to be able to dull the inherent warmth and camaraderie of Trinbagonians which find its most apt expression during Christmastime. As the words of Susan Maicoo’s now-staple ballad most appropriately put it ‘Trini Christmas is de best". (Source: Virtual Museum of Trinidad and Tobago, Nov 23, 2023) Author : Historian Angelo Bissessarsingh ( HMG) Did you know that Plum Mitan Village on the east coast of Trinidad owes its name to a plantation that existed in the area in the 19th century?Some argue about the prevalence of plum trees in the area being the origin of the name, but this is yet to be proven. Archaeological evidence suggests that as early as 650 AD the vicinity was populated by Kalinago-esque peoples who left their remains scattered throughout the hillsides which comprise the main settlement. This part of Trinidad was largely forested (and heavily) for much of the 19th century. An odd group of settlers came to the area in 1816. They were black soldiers who had fought for the British in the War of 1812. Former slaves who turned on their American masters, they were promised freedom and parcels of land. These veterans were given their due lands in isolated and forested areas to separate them from the slaves in Trinidad who might have taken their presence as an inspiration to struggle for freedom themselves. Several of these veterans were still alive in 1884 when Sir Louis De Verteuil wrote:

“The settlements of Cuare, Turure, and la Ceyba were formed, in the year 1816, of disbanded soldiers from the first West India regiment. These settlements, or villages, ranged along the banks of the rivers bearing their respective names, and the soldiers were located thereon, with a grant of sixteen acres of land to each man. They were placed, to a certain extent, under the supervision of their serjeant, who was allowed a larger and more convenient dwelling, on condition of admitting travellers to a temporary lodging, when requested so to do. Some of the locations also bordered along the road leading to the eastern coast, with a view, it seems, to keep that line in good repair, as well as to place labour within the reach of the neighbouring proprietors of estates ; but the experiment proved a complete failure the King's men (as they called themselves) being too proud to become day-labourers. In the year 1849, after the passing of the Territorial Ordinance, the lands of these and other settlers were surveyed, and fifteen acres granted, free, to each settler or his descendants ; but the lands of Cuare, la Ceyba, and Turure being of the very worst description, the occupants will be soon compelled to give up their property particularly as the tax is levied on the land, irrespective of its quality. Cacao, a little coffee, and provisions are the only productions. The cacao plantations are along the rivers Oropuche and Matura, and the article is brought to Arima on mules. The Oropuche is a fine stream, but is not accessible to craft, in consequence of the heavy surf which breaks all along the Matura shore, and of the bar at its mouth : this river is also noted for the quantity of huillias, or water-boas, it contains.” The village was one of those which sprang up in the wake of a massive spike in the price of cocoa in the 19th century which caused an economic boom. Many forested lands on the east coast were opened up to plantation activities and the town of Sangre Grande emerged as the market center. Hitherto, produce had to be transported to Arima as Sir Louis had noted. The boom was also due to land reforms introduced by governor Sir A.H Gordon in 1867 which allowed peasant proprietors to purchase crown lands at nominal rates thus creating a strong and independent farmer class. Many of these small proprietors were ex-indentured labourers from India who had served their five and ten year contracts on sugar plantations along the east coast such as in Mayaro and as far afield as Tacarigua. They used their meager savings along with bonus money (an incentive to settle in the island that was offered from 1866-80) to acquire five and ten acre parcels which they speedily transformed into cocoa estates. The area was also known for its extensive stands of mora trees and this valuable timber provided a living for many of these early Indo-peasants who culled the trees, sawed them and then sold the lumber in the booming construction industry. Much of this wood was lugged to the coast at Manzanilla and the mouth of the Lebranche River. From the 1850s onward, a weekly steamship service connected the remote coastal depots of the island to Port of Spain. This was vital for the communities like Plum Mitan that relied upon it for mails and goods because it was not until 1898 when the Trinidad Government Railway opened a spur-line to Sangre Grande, that a viable form of transport came into being. Even so, the road connecting Plum Mitan was very very bad indeed. It was dusty in the dry season and a sea of mud in the wet. L.O Innis, a venerable old Trinidadian , wrote about journeying from Port of Spain on foot to visit his father at Mayaro and somewhere in the forested area near Plum Mitan, allegedly seeing a hat lying in the path. Upon lifting the hat he was to discover a person underneath who had sunk into the mud. This story, though humorous, is a highlight of the challenges of rural communities in the period. There were no services to Plum Mitan except the establishment of a primary school by the Rev. Dr. Harvey Morton around 1904. Rev. Morton was the son of the Rev. John Morton who in 1868 founded the Presbyterian Church’s Canadian Mission to the Indians (CMI) which was the catalyst that signaled the removal of the Indian from the sphere of the cane -field to aspire to the highest ranks in the island. A bus service connected the village to Sangre Grande as early as 1912, being one of the earliest in the island. Several tradesmen in Sangre Grande plied delivery vans (horse-drawn) to the village before the cocoa market crashed in 1920 and thus Plum Mitan had daily consignments of fresh bread, ice and aerated water. There was at least one shop owned by a Chinese merchant. The collapse of the world cocoa market plunged the village into some hardship which saw the waning of the plantations and a turn to mixed cropping among the peasants. One of the quirky and colourful characters of the period was planter G.A Farrell who owned El Recuerdo Estate which was the largest single plantation in the district. Farrell was something of a genius and in addition to experimenting with agricultural science, also built (and wrecked) what must have been the first aeroplane in Trinidad as was described in 1910: “The roads are fairly graded and were surmounted without difficulty, and at the bottom of the long descent from these hills, lay El Recuerdo, about 2 miles from Manzanilla beach, my resting place for the night. The house is prettily situated on a ridge, nearly 100 ft. above the level of the King's Highway, which has been carefully leveled, round edged, and terraced. The " coupd'oeil" that presented itself at dawn next morning when I went outside the house, was truly picturesque. Each terrace was lined with a wealth of plants of all kinds, palms, crotons, colei, canna, dracenas, roses, begonias, all too numerous to recapitulate, and G. A. F. assured me that they had all been originally planted from slips just placed in the ground, and not from rooted cuttings, proof positive of the generous nature of the soil. Westward of the house, a lawn had been laid out and planted with grass, and contiguous to this plot is a small hill, on a rise of about 50 ft. from the house, known as Mt. Beverley, on which the proprietor intends to build a chalet, where he can pass a week-end far from the madding crowd, and a delightful spot it is. Right above the lofty tree-tops come with an uninterrupted rush, the cool winds of the eastern sea, bringing fresh life from across the Atlantic ; looking towards the North, the opposite slopes are one mass of the flame-coloured Immortel (Erythrina umbrosa), while immediately beneath are the engine room, drying houses, and barracks of the plantation. On the South, one looks down into rich dells with a perfect kaleidoscopic arrangement of the glossy green cacao leaves interspersed with the pods of many hues ; while on the West, Brigand Hill, about which gruesome tales are retailed in the quarter about the days of the old buccaneers, especially the renowned Blackbeard who is supposed to have opened many a dead man's chest and bottles of mm in the Caves of Brigand Hill. Further off in the blue-grey Mt. Harris forms an appropriate background. But the "piece de resistance" of the picture is a large Pois doux (Inga), which has been entirely monopolized by the cat's claw vine now in flower, and covering the tree with a veritable shower of gold. Nor is bird life wanting. Jacamars with their greeny-gold breasts flit from bough to bough, brilliant humming birds in all hues from flower to flower, the ubiquitous shrike or "qu'est ce qu'il dit", of course, is omnipresent, whilst overhead flocks of green parroquets and blue and yellow macaws fly past chattering and screeching. G. A .F. having ventilated his political opinions and finished with wine and wassail, returned from Port of Spain by first train, and we made arrangements to go at once to Nariva and Mayaro. I must here side-track a moment to narrate a rather amusing incident that occurred on his return. I have previously mentioned G. A. F.'s retainer, Harris, who in a humble way reminded me of his illustrious prototype, the Harris of Mark Twain in " The Tramp Abroad." Those who have read that book may remember that America's champion jokist always insisted on Harris experimenting in the first place on every new enterprise or undertaking. So it is with mine host and his Harris. G. A. F. happens to be a very ingenious mechanic, and has with infinite care and labour built him an aeroplane. The machine had just been finished, and lay on the terrace before the house ready for trial. G. A. F., being a very large and heavy man, thought that it would be better to have the trial trip conducted by a light weight,and called Harris for that purpose. Having shown him how to handle the lever and explained the steering gear, he ordered him to get into the aeroplane and try to clear the curing house, about 50 ft. below the house terrace, and drop lightly, if possible on the high road, another fall of about 30ft. Poor Harris jibbed, so G. A. F. , who stands about 6 ft. 2 in. in his socks, made a dive for him with a hand like that of Providence, and sad to say, Harris "took bush." Plum Mitan’s strong agricultural base took a hit during Word War II when in 1941 the American Army constructed the Wallerfield Airbase in Cumuto. This employed hundreds of local workers, many of whom turned their backs on their farms to earn a quick dollar working for the Yankees. Plum Mitan was however , to survive this rip-roaring period and keep its identity as a hardworking agricultural community. Largely forgotten for decades by successive governments, it is only in the last three years that aid has come to the farmers and villagers in the form of pipe borne water and the installation of massive pumps to prevent flooding of the farmers’ crops. Photos : A roadway connecting Manzanilla and Sangre Grande near Plum Mitan (1910). A cocoa estate house at San Leon near Plum Mitan in the 1920s. (Source: Angelo Bissessarsingh;s Virtual Museum of Trinidad and Tobago, Sept 24) Credit : Historian Angelo Bissessarsingh.

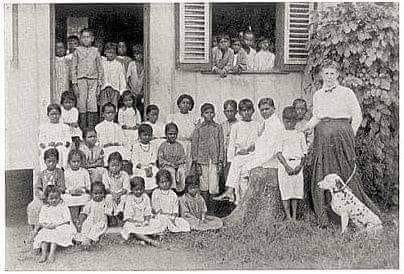

It's that time of year when Christmas Treats for Children up to 2019 was a common occurrence in most ECCE Centres , primary schools, villages and communities throughout Trinidad and Tobago. But how many of us are aware of the origin of the first Christmas Treat for children in Trinidad ? This article written by Founder of VMOTT Angelo Bissessarsingh provides us with the answer. ___________________________ When indentured labour began entering Trinidad from India in 1845, the overwhelming majority of these people were Hindus with a small number of Muslims. Christmas was an unknown concept to them of course and here in the Caribbean, they would have their first contact with this festive season. The labourers were bound in five and ten-year contracts to sugar estates (cocoa plantations to a lesser extent), and from 1866-1880, were offered an incentive to remain in the island and form a peasantry which would provide a seasonal workforce for the plantations. Whilst bound to the estates, a few owners and managers of a more benign disposition would have introduced Christmas to the lives of the workers. Almost certainly, this was the case of the Orange Grove Estates conglomerate which was managed by the foresighted William Eccles (1816-59), who founded an industrial school and orphanage in Tacarigua, under the auspices of the Anglican Church. This paternalistic approach would have also pertained at Lothians Estate near Princes Town where the kindly Irishman, H B Darling was the proprietor. The coming of the Rev John Morton and his wife, Sarah, in 1868 to establish the Presbyterian Church’s Canadian Mission to the Indians (CMI) began a long process of trying to find the right method of evangelisation and at once hit upon education as the key. Dozens of schools were founded across the island with concentration on the areas where there was a predominantly high population of ex-indentured labourers and their children. Churches in Quebec, Nova Scotia and Ontario would forward to the CMI large boxes filled with small bibles, toys, religious books and sometimes clothing (made by the Auxiliaries of the Women’s Foreign Mission Society) which would be distributed in the schools. The ladies of the Chalmers church in Quebec were particularly magnanimous for in addition to the regular fare, they sent along dressed dolls, pocketknives, school bags, marbles, pencil boxes, scissors, whistles, necklaces and watches. The whole was often valued at $60 which was quite a large sum in those days, and this generosity from Quebec was a steady expectation from the early 1890s right up to 1914. One can only imagine the excitement of the poor children of the canefields upon receiving such elaborate presents. Mrs Morton described one such treat in 1877, at Mission Village, which would later become Princes Town: “Examination of the Mission School Miss Blackadder’s began at 12 sharp. A number of white people present—Mr Darling, who sent a good supply of candies and two beautiful bouquets, Mr and Mrs Frost, who sent a nice parcel of small books and cards, and some others. Children present sang nicely and, indeed, went through their exercises very well and were particularly clean. The little pictures from the box you sent were greatly prized. I hope you will be able to get some more. *“All got some candy and a large banana; that was all the treat.”* The early experiments with treats proved to be so successful for the conversion process that it spread to other parts of the CMI field including Tunapuna. At the Tacarigua school, where the very same Mrs Blackadder from Mission Village was later assigned, Mrs Morton described a treat in 1887: *“A Christmas treat early became an institution. We had seven schools to provide for. In each we examined the register and counted how many children had made over 400 attendances, how many 300, and so on. All these had cakes and candy and a little present according to the days they had made. The careless ones who had too few attendances were called up and told they could not have any present and only a small share of the sweetmeats. A very few who came in for cakes but had not come to read were sent home without anything as a warning to the rest.* *“We find this a good plan for encouraging attendance; we have adopted the same plan in our Sabbath schools, but confining the rewards to the very best children.”* The Christmas treat tradition soon spread to other denominational schools and was often accompanied by a concert. This often coincided with the auspicious annual visit by the local school inspector who would assess the progress of the students. Today, Christmas treats have become sordid affairs of sometimes dubious motives, but those who were educated in the primary schools of several decades ago still cherish memories of the joy felt at the bestowing of small gifts which meant so much. Photo description :Mrs Blackadder, schoolmistress of many years at the Tacarigua CMI school, with some of her students and Dalmatian. Circa 1899 Did you know that there were people of Chinese descent who played a critical role in the development of the local oil industry? In this article, Angelo Bissessarsingh tells of the contribution of John Lee Lum to the development of the Local Oil Industry .

JOHN LEE LUM – OIL PIONEER Author and Researcher : Angelo Bissessarsingh John Lee Lum was one of the few Chinese in Trinidad who did not come here directly. Born in Guangdong , China in 1847, he went to California , USA where he worked with thousands of other Chinese coolies to lay the track for the Trans Pacific Railroad which connected the East and West Coasts. In 1885, he came to Trinidad and set up a provision shop on Charlotte St. It prospered since there was a boom in the price of cocoa which meant that he traded provisions for dried cocoa beans which were then exported. Ever the shrewd businessman, he recognized instantly the value of having agencies in the outlying areas of the island and by 1900, owned 60 shops in villages throughout Trinidad, including La Brea, Mayaro, Siparia, Toco, Tunapuna, Sangre Grande, Chaguanas, Pointe-a-Pierre, Moruga, Princes Town and Tabaquite. Lee Lum gave credit and so was able to foreclose on many peasant-owned smallholdings. This is how he was able to acquire vast cocoa estates on the south coast and in the Montserrat Hills near Gran Couva . Lee Lum was supposed to have been the originator of a catchphrase “Chinee for Chinee” which meant that he sent back to China for labour to staff his shops. At the time (1890s) there was a shortage of coins in the island. At his La Brea shop in particular, Lee Lum issued stamped metal tokens which were square and bore his name as well as the word ‘La Brea’. Perhaps remembering the copper ‘cash’ of his homeland, the tokens had a hole in the middle which meant that they could be strung together. Estates such as those owned by Lee Lum, paid their workers with IOU slips called ‘chits’ which would be taken to the shop to be exchanged for goods. Perhaps John Lee Lum is best remembered for the role he played in the development of the local oil industry. In the 1880s, a surveyor mapping the southeastern coast noticed seepages of oil in the Guayaguyare forest. By 1893, Major Randolph Rust, a POS merchant who had been bitten by the oil bug, was in the same forest looking at the seepages. The land was owned by Lee Lum. Rust was sufficiently convinced of the commercial possibilities of oil, and undertook to provide financing for his enterprise BEFORE drilling. Backed by Lee Lum, Rust entered into a partnership with the Walkerville Whisky Company of Canada to form the “Canadian Oil Exploration Syndicate in 1901.Erecting a rickety wooden drilling rig, powered by a steam engine Rust and his men struck a rich oilsand at just 2000 feet. The recovery process was even cruder than the drilling apparatus. A large well was dug and a pulley system installed on which drill pipe dippers were dipped in the pooling oil and then dumped into wooden barrels which were then loaded on canoes and taken to the mouth of the river. Although the production of oil had begun in earnest the costs associated with the remote location were huge. Moreover, refining the oil was a problem since it had to be sent to La Brea to be distilled into fuel. In 1913, Trinidad Leaseholds Ltd who had commenced operations at Fyzabad and had opened a refinery at Pointe-a-Pierre took over the Guayaguayare wells of Rust and Lee Lum. John Lee Lum married and had three sons; Aldrich, Edwin and Oliver who were educated in the USA and England and returned to Trinidad to take over the family business which by the 1920s was one of the largest family-owned firms in Trinidad and diversifying into the importation of Chinese goods and wares. In 1914 he purchased a quantity of land at Pointe Gourde in Chaguaramas where the subsoil was suitable for road metal. A thriving quarry was operated here well into the 1930s before the coming of the Americans in WWII when the entire peninsula was ceded to them under the Bases Agreement. Lee Lum was always a supporter of the local Chinese community and in 1925 established a cooperative business for them called the Canton Trading Company which imported dry goods from China and became one of the best known retailers of Charlotte St. The first Managing Director of the Canton Trading Company was John T. Allum, a local Chinese who later branched off to form the well-known Allum’s supermarket chain which survives today as JTA Supermarkets. Lee Lum retired to Hong Kong to enjoy his wealth and died there in the 1930s. Source : A History of Trinidad Oil by George E. Higgins. Copy of photo of John Lee Lum (Source: Virtual Museum of T&T, October 5, 2023) |

T&T news blogThe intent of this blog is to bring some news from home and other fun items. If you enjoy what you read, please leave us a comment.. Archives

July 2025

Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed