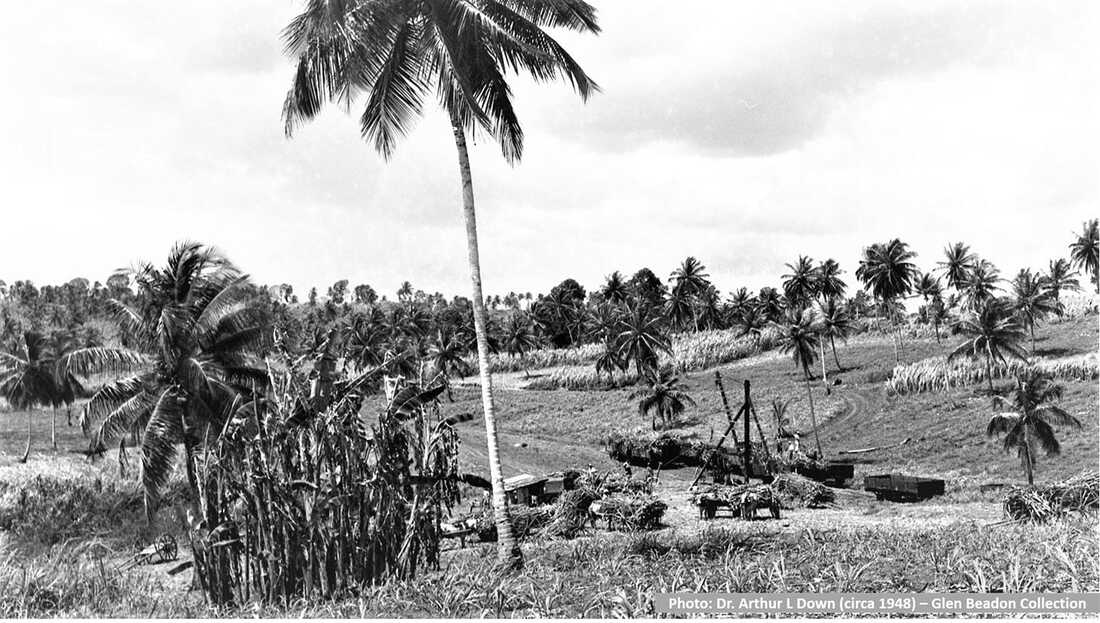

Photo by Dr Arthur Down circa 1947 - Cane at railhead being loaded upon rail cars for onward haulage to factory. Note the early timber rail wagons and old-style derrick complete with mule-power winching apparatus. Cane fields, coconut and banana trees flourish together under the tropical sunshine. A collection of animal drawn carts, awaiting their turn for loading up. A period picture that remained unchanged for almost 150 years across the Naparimas of South Trinidad. HISTORY So many factors in history are linked. A very good example of this in Trinidad is Cane Farming and the railways that served the practice. Few people today understand the role played by private cane farmers and the rich history associated with it. It is recorded that Cane Farming in Trinidad was started in 1882 by Sir Neville Lubbock, who was the Managing Director of the Colonial Company (at Usine Ste Madeleine 1870 - 1895). The idea of creating cane farmers was born out of the need to increase grinding capacity without having to increase company personnel. The advent of railways across Trinidad allowed cut canes to be transported from any part of the island to the central factories. Cane farmers would benefit from selling their produce without the need for capital investment and the cost of building and running a factory. In 1896 some of the leading planters were willing to receive immigrant farmers and their families and to allot to each half of an acre of land free of rent as a garden, to be planted as the immigrant pleased. In addition to this a certain amount of cane land was appointed to each immigrant upon which he was required to plant canes. Once cane was ripe and ready for harvesting, this cane would be purchased by the planters at a rate of nine shillings per ton, if delivered to the mill. If, however, the estate was required to cut load and cart the cane to factory, then the rate would be six shillings per ton. As time went on cane farmers increased their acreage across their own private lands and with the expansion of railways the business became much more worthwhile due to increased volume, but it did of course suffer during periods of world market volatility. The cane farmers across Trinidad became an important partner in the sugar industry and a stabilizing force in the country. Their reliance on the railway was apparent right up until 1998 when the railway between Barrackpore and Ste Madeleine was closed. To provide some idea of this association between farmers and the railway, in 1955 the Trinidad Government Railway (TGR) carried 200,000 tons of cane to factory which was about 11% of a total of 1,800,000 tonnes of canes milled that year. At that time, sugar canes were carried at rates far below cost, under what was regarded as a Government subsidy to the sugar industry. This low rate was specifically designed to help private cane farmers to get their produce to the factories. In 1956 the ‘Cane Farmers Association’ was founded and it became a highly effective mouthpiece in dealing with Government and the sugar Manufacturers. In 1963 alone there were some 11,000 cane farmers in Trinidad, and at the time they produce about 35% of the ground cane, a very respectable contribution. If we look at the 1969 figures for cane transported by rail across Trinidad it is clear to appreciate the relation between farmers and their reliance on rail transport. Out of 695,300 tons of canes transported by rail that year a total of 394,800 tons was farmers cane. The total transported by road shows that rail was, at that time, in the process of being ‘phased out’ with 1,048,400 tons carried by tasker trucks. Out of this total, only 153,000 tons was farmers cane. After the TGR folded in 1968, it was Caroni (1975) Limited which carried on the Trinidad railway tradition for a further 30 years. At first both the Northern Division at Brechin Castle and Southern Division at Usine Sainte Madeleine would continue with their rail transport divisions. The northern division was the first to go at the end of the 1976 season, but Usine Ste. Madeleine continued running trains until 1998. Extraction of high-quality farmers’ cane from the valley line in Barrackpore was instrumental in retaining this railway for as long as it did. The sugar industry in Trinidad folded five years later in 2003. We should never forget the contribution and extremely hard work made by Cane Farmers to an industry that was once a thriving concern across Trinidad and Tobago. Source: Glen Beadon 10 December 2019, Virtual Museum of TT

0 Comments

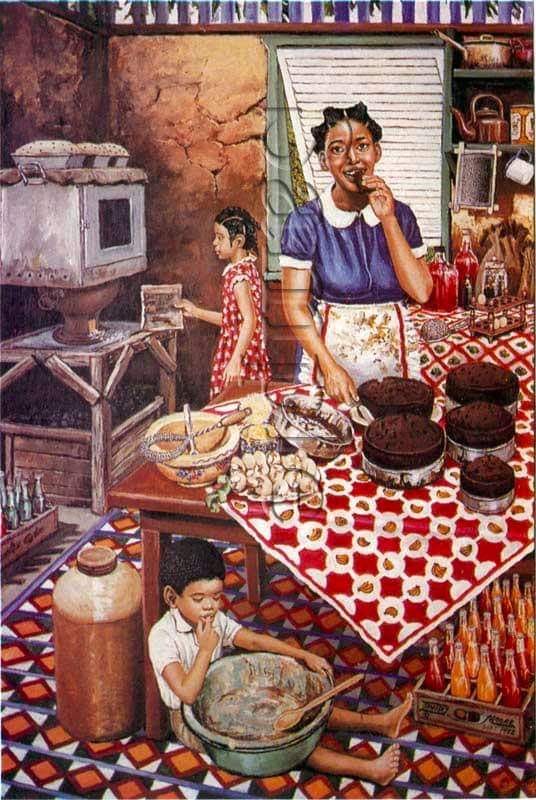

What childhood memories of Christmas past does this painting by Trinidadian artist David Moore evoke in your minds? I can vividly remember my siblings and I waiting patiently in the kitchen to be given the bowl and spoon to lick after the Christmas cake batter had been poured into cake pans for baking.

Thanks to impact of modern technology , today's women have food processors to mix the cake batter thus saving time taking turns to mix batter by hand. Modern ovens have replaced the aluminium tin ovens that was placed on coal pot as seen in this photo and for those who are too busy to spend time baking ,thanks to Kiss Baking Company one can go to any supermarket in Trinidad and purchase a delicious fruit cake. In some areas you can even order your fruit cakes and pastelles from someone who lives in your village.  It was late in April of 1979, when a poor, lonely and saddened man sat in his little, wooden gallery in St Croix Road, Princes Town. Almost in tears and failing sight, he recalled the 45-year pioneering struggle in the making and perfecting of the doubles, a national food. He was known as Singh, the doubles man, one of the several pioneers in Princes Town. Singh grew up in a little barrack room in Transport, Princes Town. He became acquainted with Chote, Dean and Asga Ali of Fairfield Sugar Cane Estate in Craignish, who were also pioneer makers and vendors of barra and chutney, kurma, pholourie, channa and other Indian delicacies. Chote related how he acquired his art from his indentured grandfather in the barrack at the Malgretoute Cane Estate. Singh agreed that he learned a few things about making and selling some of those delicacies from his associates. As a young man, he decided to go into business, and so, he filled his basket and set up at the Princes Town Triangle to offer his delicacies. Hopefully, and in good spirits, he shouted, "Get yuh barrah and chutney! Channah! Channah! Channah! Wet (curried) channah o’ dry (fried) channah!" As he continued his selling at the Triangle one day, an aged woman named Doo Doo Darlin tasted his barra and chutney. She sucked her teeth in pity and shaking her head, "No!" she told Singh,"Yuh cyah mek barrah yet mih son. De edge ah de barrah too hard. Dorg self cyah eat dat." The following day, the woman went to Singh’s barrack, and with great care, she taught him the correct method of making what she considered to be good original barra. From then, there was no turning back for Singh. When the rooster crew at four o’clock, dawn, Singh and his wife, Sookya, were up and preparing the delicacies for the day’s sale. After much labour and sacrifice, Singh and Sookya had saved enough money to purchase a freight bicycle. It was then that he was able to move with much ease and to offer his edibles to a wider market He had the grit and determination to sell and so, he focused on being an iterant barra man. He journeyed to neighbouring villages on special functions and festivals. He cycled to Cedar Hill daily during the Ramleela Festival, to nearby Craignish during Hosay (Hosein) celebration. He journeyed many miles to Barrackpore, Debe and Penal during the Phagwa festivals, also at Union Park in Marabella during the grand Easter horse racing events. The tireless barra man Singh sold his products to villagers at the Williansville Railway Station, when horse-drawn buggies plied for hire to Whitelands, Mayo and Guaracara villages. Combing his fingers though his short, grey hair, a smile played on his lips. Singh, with a measure of laugh in his voice, recalled, "Boy, sometime during the World war 11 in 1940, dey had big cock fight in Rebeca-Richmond Road, near Tabaquite down so. Ah pack up mih bike wid curry channah, barrah and hot mango chutney and Ah ride off soon morning until ah reach. Boy dat was pressure. Well, ah push dong mih bike trough de bush track right dong to de gayelle. Boy dat was cock fight foh so! All kinda bigshot man in de bamboo patch and dey game-cock fightin’ an’ money only flyin’ as dey drinkin’ mountain dew like water. Well, ah sellin’ mih stuff good, good, when ah man bawl out, 'Police! Police!' Boy! Man runnin’ like ‘gouti through de bush. I run an hide in de bush too. A! A! When ah come back to mih bike all mih barrah an’ chutney gorn. Mih channah tin empty! Like dorg lick it!" At that point his voice dipped into a sobbing tremor, his eyes turned moised as he looked down to the floor. He choked, "Only Gawd know how..." From that exciting day, Singh discontinued his sales trip to cock fighting gayelles and whey whey turfs. He settled back to the Princes Town Triangle, and sometimes at the Fairfield Junction in Craignish, alongside Chote and Dean. As the World War continued, the barra business suffered from shortages of related ingredients including flour and cooking oil. Singh heard of a Chinese shopkeeper in Mayaro, who had a hoard of cooking oil. Early one morning, he rode off on his freight bicycle to that destination, approximately 36 miles plus, to the Chinese shop, where he bought a four-gallon tin of the cooking oil, and rode back to his barrack in Princes Town. Many times after, he travelled by the TGR (Trinidad Government Railways) bus to obtain his supply. When the war ended in 1945, Singh sighed in relief, and with renewed hope and determination, he sought new marketing outlets in the Borough of San Fernando seven miles away. He staggered his vending from the Naparima Boys' College on Paradise Hill to St Benedict’s College, now known as Presentation College on Coffee Street. At alternate times, he sold at the market and on the King’s Wharf. In those far-off days, he explained that the barra was sold with a daub of peppery chutney. The curried channa—sometimes called wet or soft channa—was separately sold. One day, while selling near a well-known auto garage on the wharf, a regular worker from the garage came to buy. He ordered that Singh put a spread of the curried channa on the barra. So pleased was the customer with the combination, that the following day, he ordered, " 'Singh, boy, put some curried channa on ah barra and cover it wid anodder barra to make like ah sandwich.' " Singh said, "Oho! So,yuh want it double!" The satisfied customer returned to order, "Aye! Singh, dat 'double' eatin’ good boy! bring ah ‘double’ dey foh mih, an put de pepper chutney too." Subsequent to those days, whenever the man came to buy, Singh would ask, "So yuh come foh anodder double?" Other customers observed, tasted, and were delighted and satisfied at the unique combination. Voices were calling for more, "Can I have two doubles please?" And the orders went around; it was the origin of the name 'doubles.' Although the basic art of making the delicacies was handed down from our indentured fore-parents from India, it is known that certain changes were made as of necessity or as a creative adjustment toward a better flavour. The composition of the ingredients was altered, making it an indigenous food form. Ms Asgar Ali, Chote, Dean and Singh remain the pioneers of the doubles. Those men and their devoted wives had sacrificed and contributed to a national fast food; those who had cleared the way toward self-employment of all doubles vendors; those who had given us a simple meal, which is affordable and nutritious. The famous Ali Doubles chain emerged from those indentured roots, as well as all doubles vendors across our island and Tobago. It is regrettable that those men and their devoted wives were not recognised and applauded for their laudable contribution to the culinary art. Princes Town, the birth and home of the mighty doubles, that old freight bicycle with the doubles box should be the symbol and a tangible historic item to be preserved and displayed on a pedestal with the names of the pioneers etched in a plaque with a brief history. The people of Princes Town must keep their history and cultural heritage alive; you are a part of a noble town with a rich and enduring history—celebrate the pioneers, your heritage, your history—The home of the doubles. Source: Al Ramsawack, Trinidad Guardian, October 2019 George Arthur Roberts, born in 1890.

Leaving Trinidad, he arrives in London at the outbreak of WW1, joins up and gets nicknamed "the coconut bomber" supposedly due to his ability of throwing bombs behind enemy lines, 74 feet no less !!!! He sustained injuries from both the Battle of Loos and the Somme. After WW1, George fell in love, settled in Lewis Rd Camberwell, got married to Margaret in 1920 and had two children. When WW2 began, he joined the fire service, working from New Cross Fire Station and saving countless lives during the Blitz, he was awarded the British Empire Medal. Last year there was an online vote for people to nominate who they thought deserved a blue plaque on their home and this week, George was declared the winner. So there you have it, George was not only one of the first black men to join the British Army, but was also one of the first to join the fire service. Much respect for you Sir Source: Ancre Somme Association Scotland Chinese immigration to Trinidad occurred in four waves. The first wave of Chinese immigrants arrived in Trinidad on 12th October 1806 on the ship Fortitude. Of the 200 passengers who set sail, 192 arrived. They came, not from mainland China, but from Macao, Penang and Canton. This first attempt at Chinese immigration was an experiment intended to set up a settlement of peasant farmers and labourers. The objectives of this experiment were to populate the newly acquired British colony (Trinidad), and more importantly, find a new labour source to replace the African slaves who would no longer be available once slavery and the slave trade were abolished. It was felt that the Chinese immigrants could work on the sugar estates.

Upon arrival, the majority of the immigrants were sent to the sugar plantations. The rest were sent to Cocorite where they lived as a community of artisans and peasant farmers. Living conditions there were awful. Very few of the immigrants stayed on the estates for long. Many of those who decided to stay in Trinidad became butchers, shopkeepers, carpenters and market gardeners. The rest returned to China on the Fortitude. Of the 192 immigrants only 23 opted to stay in Trinidad. The experiment was considered a failure and was never repeated. The second wave of Chinese immigration took place after the abolition of slavery. Most of the immigrants came from the southern Guangdong province: an area comprising Macao, Hong Kong and Canton. The immigrants arrived in Trinidad as indentured labourers between 1853 and 1866. It was normal for the Chinese to migrate in large numbers to countries in South East Asia, but the period 1853 to 1866 saw them migrating on a global scale to countries such as Australia, Canada, the United States and the Caribbean. Trinidad received a small portion of this vast movement. Those who came here included both indentured labourers and free Chinese who migrated voluntarily. The indentured labourers were assigned to work on the estates, and their terms and conditions of employment were the same as those given to the Indian indentured labourers. The Chinese indentureship programme came to an end in 1866 because the Chinese government insisted on a free return passage for the labourers. The British government, which had organised the indentureship programme, felt that this was too costly, and ended the programme. The third wave of Chinese migration began after 1911 and was a direct result of the Chinese revolution. Between 1920s and 1940s immigration increased significantly. These new immigrants comprised families and friends of earlier migrants. They did not work on the estates but came as merchants, peddlers, traders and shopkeepers. In addition to the immigrants from China there were also immigrants from other parts of the Caribbean region - mainly Guyana. These were Chinese who had originally served their indentureship on the mainland. Once their period of indentureship was finished they migrated to Trinidad to seek better opportunities. Migration ceased completely during the period of the Chinese Revolution. However, during the late 1970s when China started opening up to the outside world, migration resumed once more. This was the fourth wave and continues on a small scale up to today. LIST OF VESSELS ARRIVING IN TRINIDAD WITH CHINESE IMMIGRANTS, 1806-1866

|

T&T news blogThe intent of this blog is to bring some news from home and other fun items. If you enjoy what you read, please leave us a comment.. Archives

November 2024

Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed