|

Prime Minister of the Republic of Trinidad and Tobago Dr the Hon.Keith Rowley and Prime Minister of Canada, the Hon. Justin Trudeau pause for an official photo after the Commonwealth Heads of Government meeting April 18 Prime Minister Dr the Honourable Keith Rowley raised the issue of countries making inaccurate pronouncements on Trinidad and Tobago saying that this practice has an adverse effect on the nation’s ability to stimulate growth and development. The Prime Minister was speaking at the Commonwealth Business Forum (CBF) Heads of Government Roundtable today (April 18, 2018) when he made the comment.

The Prime Minister noted that Trinidad and Tobago pursues tourism as a viable industry for growth and development. However, when some nations issue negative travel advisories on incidents of crime, efforts made in the industry are stymied. Dr Rowley also raised the subject of the categorisation of several Caribbean nations, including Trinidad and Tobago, as tax havens. This, even though the twin-island state continues to make significant steps towards fulfilling the requirements of the European Union and is FATCA compliant. The Heads of Government Roundtable is the concluding set piece of the Business Forum that allows the business community to provide feedback directly to Heads of Government in order to inform discussions at the Heads of Government Meeting. Earlier in the day Prime Minister Rowley paid a courtesy call on His Royal Highness Prince Andrew, the Duke of York at Buckingham Palace. He was accompanied by Minister of Foreign and CARICOM Affairs, the Honourable Dennis Moses, Minister in the Office of the Prime Minister and Minister in the Office of the Attorney General and Ministry of Legal Affairs the Honourable Stuart Young, Trinidad and Tobago’s High Commissioner to the UK, His Excellency Orville London and Press Secretary to the Prime Minister, Ms Arlene Gorin-George. Dr Rowley also attended a meeting with the Prime Minister of Canada, the Honourable Justin Trudeau. The meeting saw participation from leaders of Commonwealth Small Islands and Coastal States on the subject of oceans, coastal resilience and climate change. Some of the issues raised by the leaders at this meeting included the need to increase capacity of small island and coastal states to respond to climate change and the significant cost associated with protecting the environment. They also raised the need for building clear development pathways for small island states.

0 Comments

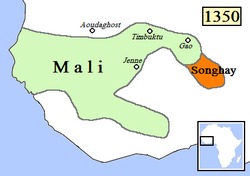

Yunus (Jonas) Muhammad Bath The Story of Muhammad Sisei (1788 – 1838)The following story has its roots in Manding Muslim civilization which dominated West Africa for three hundred years and stretched from beyond Timbuctu to the Atlantic. It helps to explain why Muslims in Trinidad are still called ‘Madingas’. IT IS A WELL-KNOWN fact that the first Muslims to come to Trinidad were from West Africa although. hardly anything is known about the nature of their presence and the extent to which they observed Islam. In the majority of cases, if anything, they must have been forced through the disabilities inhumanities of the European slave plantation system either to observe their religion in secret or to renounce it altogether. The process can be better appreciated when compared with slave experiences in other islands of the West Indies and in the Americas which is highlighted in ROOTS, the monumental work of the American writer, Alex Haley1. The history of these early Muslims’ in Trinidad is still largely obscure and the following is an attempt to cast a ray of light on this ‘area of darkness’. It is largely based on the researches of Carl Campbell published in the journal of the African Studies Association of the West Indies. Up to the early nineteenth century, there was a thriving Muslim community in Port of Spain led by one Yunus (Jonas) Muhammad Bath. Their numbers were increased by Africans who had served in the British West Indian Regiment during the Napoleonic wars. On being disbanded, some were settled in Port of Spain and some in south Trinidad but most of them apparently were given lands in Manzanilla in the north east of Trinidad. Those in Port of Spain at least petitioned the British government to return to Africa but did not succeed. One of them, however, did succeed in returning to Africa, via England, and his story certainly makes fascinating reading. His name was Muhammad Sisei. Muhammad Sisei was born about 1788 or 1790 in the Gambia. He belonged to the Mandingo people of the area, the ‘majority of whom were perhaps Muslims at the time. His father’s name was Abu Bakr (after the first successor to Prophet Muhammad) and his mother was called Ayishah (after the name of the Prophet’s wife). Sisei’s birthplace was Niyani-Maru, a village on the north bend of the river Gambia, about 100 miles upstream from the Atlantic. At the age of eight Sisei was sent some distance away to Dar Salami (Dasilami) which was one of. the centres of Islamic learning in the Gambia. There were many such places in the Gambia at the time, many of which were set up by Muslim merchants on their trading journeys through West Africa. This is one of the main ways in which Islam was spread in the region. At Dar Salami, Sisei learned to read and write Arabic and he studied the Qur’an. It is said that the writing there was done on paper which was highly prized by the Muslims. This fact acquires importance when it is remembered that literacy has been one of the greatest gifts of Islam to Africa and indeed to many other parts of the world.Sisei stayed at this school for eight years, that is until the age of about sixteen, and he returned to his hometown around 1804.. For a time after this he is said to have travelled somewhat extensively even making a journey (in1805) by sea from his hometown which was a shipping port to the French colony of Goree. The purpose of this journey was trade and perhaps to secure presents for his intended wife for it was around this time too that he was married to a cousin named Aiseta. He now settled in his hometown, setting up a school and no doubt teaching what he had learnt in Dar Salami. For five years, from1805 to 1810, he continued in this satisfying life, helping, through his teachings, to consolidated and spread Islam in the area. But the early nineteenth century was a time of great unrest in West Africa and the Gambia in particular. Apart from the Anglo-French rivalry, there were wars between rival local chiefs. It was one of these local wars which brought Sisei’s career as a teacher to an end. Rival chiefs were seeking to gain control of the banks of the Gambia river. One such chief was repulsed in the Upper Gambia and retreated downstream to increase his forces. He attacked Sisei’s hometown and along with others Muhammad Sisei was captured. He was marched as a prisoner of war to Kansala where he spent five months and then to the port town of Sikkah. There he was sold to a French slaver which immediately sailed away. Five days after sailing from Sikkah, the French slaver was intercepted by a frigate from the British navy which was trying to enforce the abolition of the slave trade especially on the West African coast. (Britain had officially abolished the slave trade from Africa in 1807). Manding Empire in 1350 Sisei was taken on board the British frigate to Antigua. Technically he was free and did not experience plantation slavery, the reason given being that it was difficult to fit free Africans into the small slave society of Antigua. Instead, he was immediately enlisted in the Third West India Regiment as a grenadier and given the name Felix Ditt. Originally, these black regiments were enlisted for service only in the West Indies. As a member of the regiment, Sisei was one of the”Kingsmen” distinguished from the slaves. He saw active service against the French in Guadeloupe and was at one time stationed in Barbados.

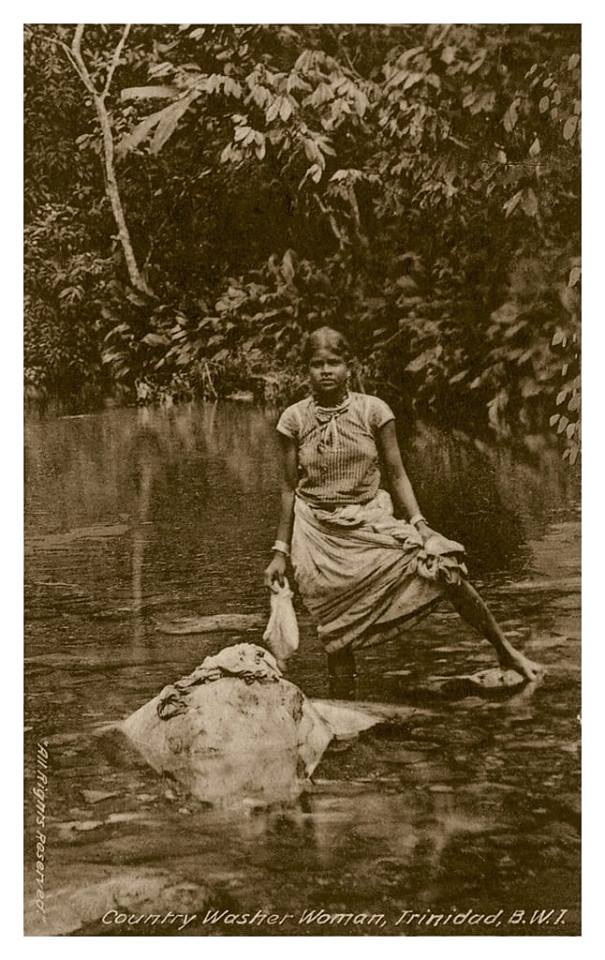

Between 1811 and 1825, Sisei the Muslim Mandingo fought alongside Africans who were Yoruba,Ashanti, Foulah, Susu, and Hausa,some of whom especially those from the last three groups must have been Muslims also. Sisei was to spend most of his life in the West Indies in Trinidad. He arrived in this island in 1816 but it was not until 1825 that the Regiment was demobilised and Sisei was discharged with good conduct.Most of the disbanded soldiers were given lands on the east coast of Trinidad, in the Manzanilla district,away from the slaves on the west coast plantations. But somehow Sisei never received or accepted land nor pension. And instead of settling down with the other disbanded soldiers in Manzanilla he moved to Port of Spain and became a member of the Muslim group there led by Yunus Muhammad Bath. Yunus Muhammad Bath it is said was a remarkable man leading a Muslim Mandingo community which lived in a certain part of Port of Spain, practised the religion of Islam and led a group existence.One of the main concerns of the group was to raise money to buy the freedom of Muslim slaves. Some of them did well economically but decided, as mentioned earlier, to petition the British government to repatriate them to Africa. One of the petitions addressed to William IV, King of Great Britain and Ireland begins with the Arabic invocation, “Allahuma Sally alla Mahomed”- Oh God, bless Muhammad. The petitioners described themselves as “the followers of Mahomed, the prophet of God”and stated that “While slaves, we did not spend our money in liquor as other slaves did and always will do”. On three occasions they petitioned the British government to repatriate them but their requests were not met. These Mandingo Muslims had to settle permanently in Trinidad. Sisei however was determined to return to Africa. With money borrowed from another Muslim, he brought a passage for himself, his wife and young child to England where he arrived about the middle of 1938. His wife whom he had married in 1831 was a creole woman from Grenada. In England, Sisei “fell under the friendly protection” of John Washington, secretary of the Royal Geographical Society, who used him to learn a lot about the languages and geography of West Africa. Washington, from whom much of these details of Sisei’s life are known, also hoped that Sisei might be useful in future British expeditions into the interior of Africa. From Washington, we get an idea of the kind of personality that was Muhammad Sisei. This Muslim was said to be quick and intelligent and a strict follower of Islam. He knew the Qur’an very well and certain parts of it he always carried with him. He even wrote Mandingo in Arabic characters and he is said to have shown the general intelligence that travellers usually associated with the Mandingoes. Muhammad Sisei left England and returned to the Gambia. His native town, Niyani-Maru, was so easily accessible by boat, that there is every possibility that Muhammad Sisei, alias Felix Ditt, did get back to the place of his birth. The story of Muhammad Sisei is a remarkable one in the history of the trans-Atlantic slave trade.Similar fascinating accounts have been researched and told, some in more detail than others-see for example The Fortunate Slave by Douglas Grant, published in 1968 by Oxford University Press,which deals with the story of Ayyub ibn Sulayman (Job ben Solomon), the son of a Fulani amir, who was captured and brought to America in the 1730’s. There must be many individual lives like that of Muhammad Sisei which could be a rich field for enquiry. And apart from individual lives, in the Trinidad context, what became of the Muslim communities in Port of Spain, Manzanilla and South Trinidad is an intriguing subject for further historical research. Sources: 1. Alex Haley’s search for his past has revealed a,Muslim ancestry. The village of Juffore also from the Gambia from where his ancestor was taken as a slave has been and still is, according to Haley, completely Muslim. To commemorate this, he has built and dedicated a mosque in Juffore itself. Slavery Days in Trinidad by C R Ottley, Trinidad , 1974 Mohammedu Sisei of Gambia and Trinidad c. 1788-1838 in Bulletin of the African Studies Association of the West Indies, N o . 7 by Carl Campbell. Originally published in The Muslim Standard (Trinidad) April 1977 issue. 1. ARIMA is the Amerindian word for “water”. It was so named as the village was built around a river. 2. AROUCA is based around the word “Arauca”, which is the true name for the so-called Arawak. 3. The adjacent beach, BALANDRA, is named after a type of boat that docked there. 4. BARATARIA is possibly named after a prank involving a fake island of the same name in Cervantes’ Don Quixote. “Barato” itself means cheap. 5. BICHE is named after the French word for “beast” because it was first started off as a settlement for hunters. 6. The settlement was first called Ladies River, but later on a French surveyor named it after the French term for “washer-woman” -BLANCHISSEUSE. 7. When boats were docked in Port-of-Spain, they were carried along the bay to be cleaned. This was called “careening” and so sprang the name CARENAGE. 8. CAURA was based off of an Amerindian word “Cuara” which meaning is lost now. The settlers of Caura were said to be so lazy and secluded that their village never thrived and was left mostly abandoned. A CORRECTION MADE BY A DESCENDANT FROM THE CAURA AREA: Caura ancestors were not lazy. They carried their church brick by brick to the Lopinot Valley. A dam scheduled there was never built and the Government never gave them back their land. 9. When the Spanish sailors arrived at this coast, they noticed many tall cedar trees. And they called it the Spanish word for cedars, CEDROS. 10. CHAGUANAS is named after the group of indigenous peoples that lived there, known as the Chaguanes. Smaller villages in Chaguanas were so named to positively motivate its early settlers - Felicity, Endeavour, Enterprise. Former Tobago House of Assembly (THA) leader Orville London at a function held by the Tobago Hindu Society in 2015. Source: Tobago Hindu Society Facebook page. Construction for the first Hindu temple in Tobago will begin soon, according to the Tobago Hindu Society.

The holy place with be built on land donated by the Tobago House of Assembly (THA). The Society was founded 35 years ago by Trinidadians working and visiting the sister-island who sought a place for worship formed the organisation. According to the officiating pundit Ramdath Mahase, the members came together to practice their religion, culture and traditions, but there was no space for them to do so. In 2014, the former THA administration granted the Society four lots of land at Old Government Farm, Signal Hill for the Temple and Cultural Centre. The members were encouraged to revive the Tobago Hindu Society and since they have worked tirelessly to promote the Hindu Dharma and Indian culture in Tobago. An annual Indian Arrival Day and Divali celebrations are hosted by the organisation The group will now be able to conduct its religious and cultural activities on its own grounds. Source: Daily Express, April 5. The Honourable Fitzgerald Hinds, Trinidad and Tobago's Minister in the Ministry of the Attorney General and Legal Affairs, and Prime Minister Justin Trudeau taken at a luncheon hosted by Prime Minister Trudeau during the recently concluded Summit of the Americas in Lima Peru.

Wonder how many of us growing up in rural communities in Trinidad remember the Village Panchayat ? The word “panchayat” literally means “assembly” (ayat) of ( panch) wise and respected elders chosen and accepted by the local community to give advise or settle disputes among individuals. My grandfather Prabudhas, was employed as a lawyer's clerk in the 1950s, therefore the villagers of Quarry Village, considered him the village elder and thus they would seek his advise and bring their problems to him . As a little child growing up I always wondered why so many people paid him regular visits on an afternoon. When asked my father said " they having a panchayat". Now that I reflect the concept of the Village Panchayat was in the early 1950s and 60s a novel approach adopted by village elders in settling disputes and solving problems of villagers in a peaceful manner Source: Virtual Museum of T&T During peak turtle nesting season (1 March—31 August), five of the seven sea turtle species found globally return to Trinidad’s beaches to lay their eggs. Trinidad is the second largest leatherback nesting site in the world. Two months later, turtle hatchlings emerge (especially from June to August). Witnessing the nesting ritual, and clutches emerging from the sand, is an unforgettable experience

Where giant leatherbacks come ashoreTrinidad is one of only a few places in the Caribbean where the giant leatherback female practises her timeless “family tradition” of returning to the place where she was born to lay her eggs. The sight of these huge creatures swimming in the rough waves of the Atlantic and then making their way up on to the beach is incredible. The whole process of watching her give birth to hundreds of eggs — from the digging of the hole with her flippers, to the “backfilling” after the delivery, to her return to the sea to mate again — can be witnessed on any north or east coast beach, but especially at Matura and Grande Rivière (here you can see up to 50 on some nights). Trinidad is the second largest leatherback nesting site in the world, with more than 6,000 of these heavyweights (up to 2,000lbs) travelling across the Atlantic to nest on the north and east coasts every year, from 1 March to 31 August. About two months later, the clutch of babies will emerge, like magic, from the sand pit. (Peak season for seeing hatchlings is June to August) Nesting grounds for five different turtle speciesThis country is home to five of the seven species of sea turtles found globally; all are on the International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN) Red List. The leatherback and olive ridley are listed as vulnerable; the green and loggerheadas endangered; and the hawksbill is listed as critically endangered. Three species — the leatherback, hawksbill, and the green turtle — nest on the beaches. Only a few dozen hawksbill and green turtles (40 at most) nest on our beaches each year. The loggerhead and olive ridley are less common locally but they are occasionally sighted at sea. There have been a few nesting records but these are few and far between. Where giant leatherbacks come ashoreTrinidad is one of only a few places in the Caribbean where the giant leatherback female practises her timeless “family tradition” of returning to the place where she was born to lay her eggs. The sight of these huge creatures swimming in the rough waves of the Atlantic and then making their way up on to the beach is incredible. The whole process of watching her give birth to hundreds of eggs — from the digging of the hole with her flippers, to the “backfilling” after the delivery, to her return to the sea to mate again — can be witnessed on any north or east coast beach, but especially at Matura and Grande Rivière (here you can see up to 50 on some nights). Trinidad is the second largest leatherback nesting site in the world, with more than 6,000 of these heavyweights (up to 2,000lbs) travelling across the Atlantic to nest on the north and east coasts every year, from 1 March to 31 August. About two months later, the clutch of babies will emerge, like magic, from the sand pit. (Peak season for seeing hatchlings is June to August) Nesting grounds for five different turtle speciesThis country is home to five of the seven species of sea turtles found globally; all are on the International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN) Red List. The leatherback and olive ridley are listed as vulnerable; the green and loggerheadas endangered; and the hawksbill is listed as critically endangered. Three species — the leatherback, hawksbill, and the green turtle — nest on the beaches. Only a few dozen hawksbill and green turtles (40 at most) nest on our beaches each year. The loggerhead and olive ridley are less common locally but they are occasionally sighted at sea. There have been a few nesting records but these are few and far between. Trinidad is the second largest leatherback nesting site in the world, with more than 6,000 of these heavyweights (up to 2,000lbs) travelling across the Atlantic to nest on the north and east coasts every year, from 1 March to 31 August. About two months later, the clutch of babies will emerge, like magic, from the sand pit. (Peak season for seeing hatchlings is June to August Nesting grounds for five different turtle speciesThis country is home to five of the seven species of sea turtles found globally; all are on the International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN) Red List. The leatherback and olive ridley are listed as vulnerable; the green and loggerheadas endangered; and the hawksbill is listed as critically endangered. Three species — the leatherback, hawksbill, and the green turtle — nest on the beaches. Only a few dozen hawksbill and green turtles (40 at most) nest on our beaches each year. The loggerhead and olive ridley are less common locally but they are occasionally sighted at sea. There have been a few nesting records but these are few and far between. Where giant leatherbacks come ashoreTrinidad is one of only a few places in the Caribbean where the giant leatherback female practises her timeless “family tradition” of returning to the place where she was born to lay her eggs. The sight of these huge creatures swimming in the rough waves of the Atlantic and then making their way up on to the beach is incredible. The whole process of watching her give birth to hundreds of eggs — from the digging of the hole with her flippers, to the “backfilling” after the delivery, to her return to the sea to mate again — can be witnessed on any north or east coast beach, but especially at Matura and Grande Rivière (here you can see up to 50 on some nights). Read the original article here |

T&T news blogThe intent of this blog is to bring some news from home and other fun items. If you enjoy what you read, please leave us a comment.. Archives

April 2025

Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed