|

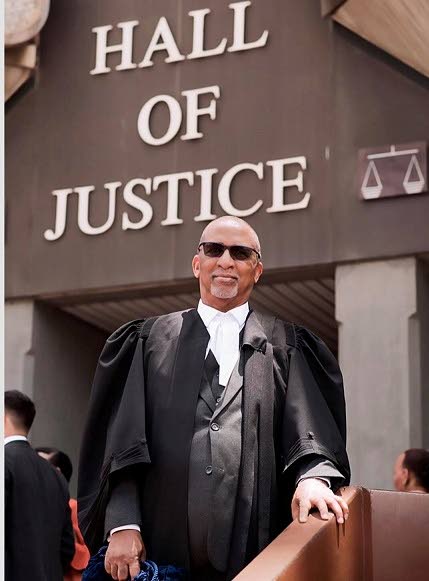

Allan Noreiga, a former schoolteacher, stands outside the Hall of Justice, Port of Spain after he was called to the bar. Why the fuss about passing the Secondary Assessment Entrance (SEA) exam and getting into a prestige school? Allan Noreiga is at a loss to know. His era takes us back almost five decades to the days of the common entrance (CE) exam which he failed. Yet he made it through professionally, becoming a teacher and a school principal and supervisor, and just recently a lawyer.

“I did not pass common entrance,” he said of the then 11-plus examination overseeing the transition from primary to secondary school. “And look where I am today,” said the retired school principal and supervisor, who made the transition from the classroom to the courtroom after 40 years in education. Honoured at one point as teacher of the year, a certified mediator and member of the Teaching Service Commission (TSC), Noreiga recalled while at primary school, “I was a playful fella. I did not like school much. My favourite day was Saturday. During the week it was a struggle for me to get up, but not on a Saturday.” In that era, primary schools catered for students like Noreiga who failed the CE exam, giving them a second chance. They were put in a standard four class where teachers taught the equivalent of form one work and gave them an opportunity to write what was called “school-leaving.” “I did school-leaving and ended up going to Fyzabad Anglican Secondary which was then known as Fyzabad Intermediate. When I went to Fyzabad Intermediate I was seen as the class clown. People used to make fun of me. My class teacher would send me to the supermarket to buy groceries and take to his home. Today that will be considered child abuse. “But by the time I got to form five, I graduated at the top of the class. I was the most outstanding graduate in my year,” Noreiga recalled, underscoring the adage that it is not where you start but where you finish that matters. Getting his first job as a checker at the Ministry of Works was an eye-opener for the very Afrocentric Siparia resident, who in those days, even before the Black Power movement, wore dashikis and an afro hairstyle. He is convinced his belief and philosophy was what prevented Barclay’s Bank, now Republic, from hiring him. At works, he said, “I learnt about this thing called ‘ghost gangs,’ where people were collecting salaries but not working. There were police investigations, people were under scrutiny and there were arrests and convictions. “ On the advice of one of his seniors, that this was not the environment for someone of his character and qualification, Noreiga enrolled at the Mausica Teachers' College, graduating two years later and getting his first teaching job at Clarke Rochard Primary School in 1972. Over the next 40 years, as he continued to educate himself, he was promoted to his alma mater, Fyzabad Anglican Secondary, moving up the ladder to vice principal and then principal of Siparia Junior Secondary, now known as Siparia East Secondary, and school Supervisor III in the Caroni education district where he finally retired in 2010. During those four decades he spent in education, Noreiga nursed a passion for law. He was inspired by cops-and-robbers shows like Perry Mason on his black-and-white television, and newspaper coverage of major court cases. For some reason he was never accepted to the University of the West Indies to satisfy this dream, and his parents were too poor to pay for him to attend university in England like some of his peers. “Teaching was always my forte,” he said. “ I enjoyed helping to transform young people and see them grow to be the best they could be. But things in law always interested me. Although my parents never went to secondary school and did not finish primary school, my mother saw the value of education and the value of reading. “We always subscribed to buying the newspaper, as the newspaper was an avenue to be educated. We followed all the major cases that were reported. Outside of the comic strip and major news stories, the big part for me was to follow the court cases. I was inspired by the reporting of verbatim evidence of big cases by then court reporter John Babb. I would go to court. I remember attending the Abdul Malik case and other cases. It was fascinating to see the play between the prosecution and the defence and the judges and how witnesses were handled. “It is a far cry from today, because of the kind of terror strategy where the society is so cowed that people would not bear witness to some of the crimes, so the criminals seem to have the upper hand. Long ago people would come out and give evidence. They had no fear, but now once you are a witness, you are marked for death. You are a dead man.” While teaching at Fyzabad Anglican, one of his colleagues was former president Anthony Carmona, who left teaching to study law in Jamaica and encouraged Noreiga to do the same. “I applied a couple times to the UWI, but I was never accepted. I saw students I taught getting accepted to the law faculty and so I resigned myself to serve in education. I told my students if I do a good job as a teacher, there would be less people to prosecute.” When he retired, Noreiga contemplated what to do to occupy himself in terms of work, but something that would not take away from his retirement and plans to travel. “It dawned on me that with so many institutions offering degrees in law ,and ability to fund my continuing education through the Government Assistance for Tuition Expenses programme (GATE), which catered for the over-50s at the time, I decided to pursue my lifelong dream.” On June 10, he was called to the bar, presented by former commissioner of police, attorney James Philbert, out of whose chambers he works. Present to witness the realisation of this dream was his friend and former colleague Carmona. “For somebody who never passed common entrance, that was beyond my wildest dreams, you know. It is quite an achievement. I never gave up, and that is the lesson I want to leave. Never give up. Always follow your dreams.” Source: Newsday, July 2019 In 1988, Trinidad-born Andrew Madan Ramroop became the first man of colour to own a business in London's prestigious Savile Row.

The achievement came 18 years after he had migrated to England from his home at Maingot Road, Tunapuna, where he was born on November 10th, 1952. In 1970, Ramroop left Trinidad aboard the luxury liner Northern Star and headed to England with hopes of beginning a career as a tailor's apprentice. He, however, was turned down for many jobs on Savile Row. "In those early days, my accent wasn't what it is now and I was applying for jobs to be at the front of the shop to cut and to fit and to meet clients," Ramroop told the BBC. "People wanted to protect their own businesses and they were being realistic in saying this guy won't suit the front of the shop," he said gratiously. Ramroop began his London training as a backroom trainee for a Savile Row institution, Huntsman & Son. In 1974, he found a position as an assistant cutter with Maurice Sedwell—the only shop on Savile Row that would hire a non-white tailor. Ramroop mastered his craft, and worked his way to the top, becoming managing director of the business in 1982 and then buying the company in 1988. In the early days, Ramroop was confined to making alterations. The big break came when a client personally asked for him to oversee an entire fitting. Ramroop's reputation was soon sealed through personal recommendations - and at one point he was dressing half a dozen British cabinet ministers. Famously, he also designed the cashmere jacket worn by Princess Diana in her infamous 'Panorama' interview on British television. Over the years, Sedwell sold Ramroop shares in the business, until he had accumulated 45%. The crunch time came in 1988 when Ramroop wanted to leave to set up his own business. Sedwell eventually persuaded him to stay and sold him a further 45% in the business. Eight years after taking over the business, Ramroop expanded the premises from 500 to 3,000 square feet. Located on London’s Fleet Street, Maurice Sedwell Ltd. grew from a gold medal-winning tailor shop to one of the UK’s best known names in Bespoke Tailoring. Today, he owns and runs Maurice Sedwell on 19 Savile Row, making bespoke suits for customers around the world. Ramroop has been featured in a BBC 2 documentary on Black Firsts. He has been named by 'Complex' as one of Britain's Greatest Designers. Among other accolades, Ramroop was the first tailor to be awarded a professorship at the London College of Fashion for distinction in his field in 2001 and, in 2005, was awarded the Chaconia Medal Gold by the Government of Trinidad and Tobago. In 2008, the Master Tailor founded the Savile Row Academy (SRA) to train the tailors of tomorrow, and was also handed an OBE honour from Britain's Queen Elizabeth II. Video via BBC London |

T&T news blogThe intent of this blog is to bring some news from home and other fun items. If you enjoy what you read, please leave us a comment.. Archives

July 2025

Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed