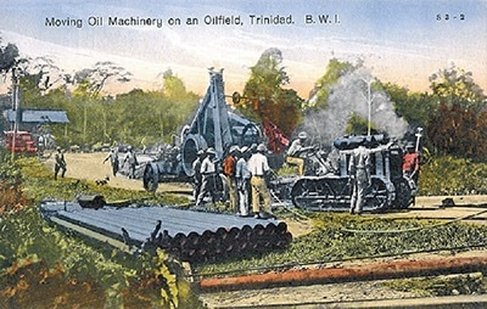

Many times we tend to forget the tremendous sacrifices of our forefathers in creating the present landscape. The herculean effort of these men are oftentimes blurred as to deny them their place in history and to deny their descendants a share in the economic windfall. Fyzabad needs to have a monument erected to these men who braved malaria, yellow fever and dengue to make their country, T&T, a more prosperous nation. We salute them for their heroic efforts. —Rudolph Bissessarsingh Angelo Bissessarsingh Published: June 15, 2014 The pioneering days of the Trinidadian oil industry of the early 20th century were filled with incidents of heroism and toil which laid a foundation for the economic prosperity with which we are blessed. When Capt Walter P Darwent drilled the first well at Aripero in 1867 it was in an area of moderate cultivation. When Major Randolph Rust prospected and struck oil in 1902 it was in primaeval jungle near Guayaguyare. Since there was no road access to the area, manpower and equipment were sent to the east coast by steamer and then ferried four miles up the Pilot River on rafts and canoes where a site had been cleared and levelled by hand. So, too, in 1913-19, the cocoa plantations and virgin forests outside the little agrarian village of Fyzabad drew the attention of oil prospectors. Trinidad Leaseholds Ltd began the march in 1913, acquiring lands, leases and oil rights from the peasant farmers. Apex Oilfields Ltd, led by the formidable Col Horace, also began acquiring lands at Forest Reserve, Fyzabad, both from peasant cocoa proprietors and by lease from the Crown. Most of these lands had to be cleared for the erection of drill sites, housing camps (for white expatriate staff), refineries, roads, pipelines, and all the infrastructure necessary to make the extraction of oil feasible. Roads, in particular, were vital to the industry, as the use of the motor car was imperative. For example, Trinidad Leaseholds had fields at Barrackpore near Penal, and also at Fyzabad, more than 20 miles away, and a refinery at Pointe-a-Pierre, another 18 miles from Fyzabad. In the infant days of the industry, the bulldozer was still unknown and most of the work of clearing the forest and laying trajectories for roads fell to an amazing class of labourer, now forgotten in history, called the Tattoo gangs. Corduroy roads Tattoo gangs consisted of both men and women, who lived as peasants near the area of development. The men were powerful with an axe and hewed thousands of trees to make clearings in the forest. The women would cull the underbrush with cutlasses before firing the whole. Logs would be dragged by oxen (later crawler tractor) parallel to each other and smeared with a layer of gravel and clay to create corduroy roads. These logs were known as “cut dry” and were split lengthwise in four pieces, with each bit being paid for at the rate of a penny each. Corduroy roads were essential especially in the low-lying and swampy spots, as they allowed the free passage of machinery and vehicles on a surface which would not speedily become depressed or pockmarked. Hardy oxen also played a special role in the development of oilfields in Fyzabad. Essential equipment and pipes for the establishments in Forest Reserve were brought by steamer from Port-of-Spain to the mouth of the Godineau River, near Mosquito Creek, and then loaded on a barge. The barge would proceed upriver to a landing place on the old St John’s estate, where a canal had been dug in the 1830s by the owner, De Godineau. The bank here was steep, so straining oxen would be used to heave the equipment up to the flat area above the river, where it would be taken by cart or truck to Forest Reserve. In areas where hilly or rolling terrain impeded the progress of roads, the Tattoo gang performed monumental labours. Writing of his experiences in the oilfields of 1923, PET O’Connor says: “There were few labour-saving devices. “Heavy equipment was headed into place by manpower, the forests were cleared by axeman and well sires and roads were graded by that unique breed of men and womenfolk called the tattoo gangs. Earthwork was paid for by the cubic yard, dug and moved, and the tattoo gang could move mountains. The men dug the wet earth with fork and shovel and piled the wooden trays high for their women partners to head to the ‘fill’ in an endless procession to and from like a swarm of bachacs . The bulldozer has replaced the tattoo gang, but the miles of road through our forests remain as a silent monument to a very special breed of men and their womenfolk who have passed into oblivion.” The usual rate for a cubic yard of earth, dug and moved, was a shilling. If anyone has ever dug wet, clayey soil, then they can appreciate the awesome effort of the Tattoo gangs. By the late 1920s, crawler tractors and bulldozers had replaced the gang. The oil wealth of Trinidad was not won by “suits” in boardrooms but by the sweat of thousands of forgotten pioneers. It is this aspect of history that has been too long neglected. Source: Guardian, June 24, 2017.

0 Comments

Your comment will be posted after it is approved.

Leave a Reply. |

T&T news blogThe intent of this blog is to bring some news from home and other fun items. If you enjoy what you read, please leave us a comment.. Archives

July 2025

Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed