|

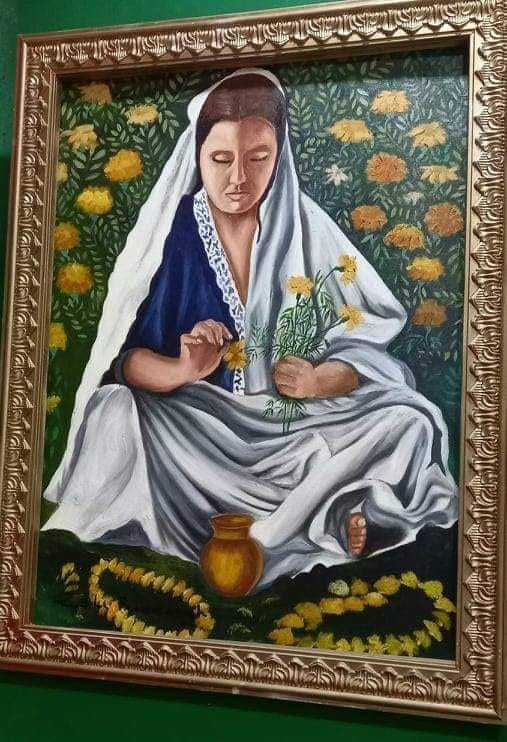

Author : Professor Angelo Bissessarsingh ( HMG) Virtual Museum of Trinidad and Tobago, (Published by Patricia Bissessarsingh, Nov 7, 2023) In the first chapter of this three-part series we looked at the religious awakenings of Hinduism under indentureship among the Indo Trinidadians of the 19th century. This consciousness of self and personal doctrine was largely due to the formation of small villages as Sir Louis De Verteuil noted in 1884: “Many have already availed themselves of the offer, and have thus become permanent settlers. At first they were granted 10 acres of land, worth £10, considered as equivalent to the passage-money. As a rule, a locality is selected, surveyed in lots of five acres, and a settlement is thus formed of Indian immigrants only; and an Indian name is given to the settlement. Thus we have the Calcutta, the Madras, the Barrackpoor, and the Fyzabad settlements. The immigrants are thus encouraged to form small communities, speaking the same language, and having the same habits and ways.” In these settlements, village life went on much the same way as it had in India for thousands of years. The community council of the panchayat was revived and festivals observed regularly. Divali was not initially foremost among these. It began as largely a family affair among the immigrants since its celebration as a neighbourhood occasion is not mentioned anywhere in the writings of the 19thcentury. The all-important deya was most likely moulded from the earth of the dooryard of the homesteads formed by the Indians in their villages and filled with coconut oil made by themselves from nuts grown on their own land. Phagwa was a much larger concern since its riot of colours and very nature made it a village event. Divali truly emerged as a large-scale festival in the 20th century, about a decade or so after the end of indentureship in 1917. It began to take on an elaborate dimension with bamboo being split into fantastic scaffoldings wherein thousands of deyas would be placed to shine forth . The sound of bursting bamboo is still something which breaks on the ear and heralds the Divali season and it is a pastime indulged in by all the youths of the community regardless of colour or creed. Deyas were also being mass produced by potters, especially along the Southern Main Road from Chase Village to Chaguanas where they still ply their ancestral trades today. Along the main road and Cacandee Road in Felicity is where the first large community Divali displays began to occur in the 1950s. Anthropologist Morton Klass lived for a while in the area whilst observing the villagers and noted: “This is a festival of lights said to be in honour of both the goddess Lakshmi and of Lord Rama’s return from the forest. It falls on the thirteenth day of the first half of the month of Kartik or around November, and is one of the most happily and eagerly anticipated of holidays . Every house is cleaned , fresh curtains are hung and special delicacies are prepared. Around each house a display of deyas is set out. During Divali the maximum number of deyas that the family can afford is displayed. The deyas are lighted at sunset and mos of the children and old people remain at home to keep them refilled and burning. There is a service in the Siwala in the evening but few except the most religious attend and most of these for a short time. Most of the younger adults set out and lighted their own deyas go walking through the community to see the display of others.” Stay tuned for the final installment of this series to find out how Divali emerged from its enclave in the Indo Trinidadian villages to achieve national holiday status and its continued evolution. Painting courtesy Rudolph Bissessarsingh

0 Comments

Leave a Reply. |

T&T news blogThe intent of this blog is to bring some news from home and other fun items. If you enjoy what you read, please leave us a comment.. Archives

June 2025

Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed