|

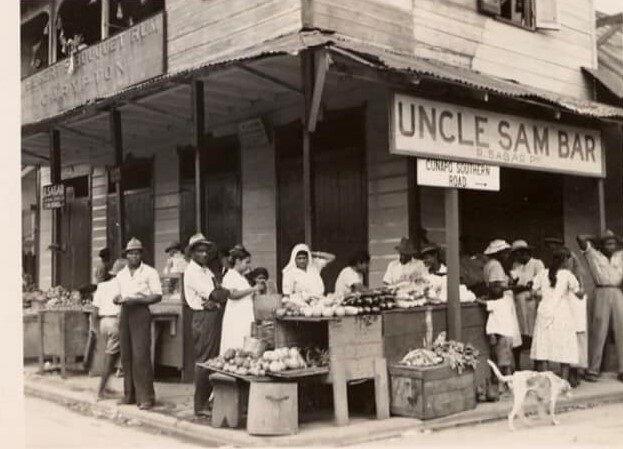

Herman Gajadhar holding a photograph of his younger self The children attending Cunaripo Presbyterian Primary School in the 1930s had a rainy season problem. To get to classes meant walking many kilometres from the surrounding villages of Howson, Jaraysingh, Cheeyou, Nestor and Hassanali, places south of Sangre Grande that you may never have heard about. Back then, every road in these villages of rice and cocoa, coffee and tonka bean was a muddy mess. So the boys would wash their shoes at a well near the entrance to the hilltop school, while the girls cleaned theirs at a trough on the compound, before daring to step into the headmaster’s building. Infant Herman Gajadhar had no such problem. Because he owned no shoes. Gajadhar told us this story over a few beers at his home in Guaico, this week. He is now 95 years old, with a perfectly intact memory, and up to a week ago, was driving around Sangre Grande, slowly, and probably causing a traffic jam. Gajadhar was born into a family of 11 siblings, his parents, rice planters and cocoa farmers, living in the lowlands in Cunaripo. They were Hindus, one generation out of indentureship, but the Canadian Mission to the Indians (CMI) opened its school nearby, and education meant a chance to avoid a life as a lagoon or plantation labourer. Gajadhar said: “My father was a good gardener. My mother remained home to cook for us. But one thing, they made sure all of us went to that school. And in those days, the best job you could get was to be a teacher, or otherwise, it was working the riceland or with your father in the estate. But he made sure I got my education, so I didn’t have to do this all my life.” He did not squander the chance at school. Gajadhar was identified as a high performer and chosen for the pupil/teacher system where he assisted in teaching classes while supervised and monitored by the schoolmaster. He was 14 years old when he was paid his first salary of $12 a month. With it, he bought his first pair of shoes, the rubber-soled, canvas upper “washikong”. Gajadhar wrote yearly exams, which qualified him to attend the Naparima Teacher Training College in San Fernando, and by age 18 was an accredited teacher, working for a $20-a-month salary. His first assignment was a return to Cunaripo Primary School, before teaching stints at Fishing Pond, Sangre Chiquito and Plum Mitan Presbyterian schools. This was 1940s and ’50s Sangre Grande, and life was far different. The Trinidad Government Railway connected this East Trinidad town to Port of Spain, Siparia and Rio Claro, but you had your entertainment right here within bicycle distance. Your alcohol and lime was at Uncle Sam Bar. And there was the “theatre” of Samuel Juteram, the rags-to-riches owner of the Apollo Cinema, where Gajadhar went on a Friday to see the Indian films, and on a Sunday for the Hollywood movies, always in the “pit” where a seat cost 12 cents. Who needed the rest of the island, said Gajadhar, when you had your beaches, past the swamplands in Fishing Pond Village, or in Bande de L’Est where you could catch crab and make a cook at night, in the schoolyard on a weekend. Meeting place: Gajadhar’s liming spot in Sangre Grande—Uncle Sam Bar. And especially since you had liming partners like Isaiah James Boodhoo (1935-2004), who also started as a CMI pupil/teacher, but would go on to become one of the region’s critically acclaimed artists. Long before that, Boodhoo was the leading “girls man” in the town, with the gift of gab, good at cricket, cards and everything else. Gajadhar would be tamed in his 30s when he married a reverend’s daughter, Elodie, and settled down to father two sons, Trevor and Addison, and teach countless children at Guaico Primary School over a decade. He would qualify to teach at the secondary school level, and older people along the Atlantic Coast may remember him at schools in Rio Claro, Manzanilla and Guayaguayare where he taught the subject principles of business (POB). It also appears he employed these business principles because he started investing in real estate, taking loans and buying land cheap, and reselling when the price increased. Meanwhile, he became a respected elder at the Morton Memorial Presbyterian Church where his wife was secretary and singer. That school closed about ten years ago. In 2021, he gave a video-recorded interview where he told about his volleyball talents, wedding sermons, the need to bring back the church harvests and village councils, and how sometimes an entire train carriage was filled with Presbyterians going to Arima or San Fernando. After his retirement, Gajadhar opened a private secondary school in Sangre Grande where accounting, shorthand and typing were taught. His wife was a teacher, and he the principal. He also let us know that he wrote his own book, A Secretary’s Companion. flashback, 2001: Herman Gajadhar. —Photo: Morton Memorial Presbyterian Church Two years ago, Gajadhar’s wife died at age 86. One son is in Canada. The other settled in the home village of Cunaripo.

So Gajadhar now spends his time in a comfortable armchair, near a cabinet filled with sporting trophies, school and long-service awards, being visited by church friends and neighbours. On the wall across from him is a framed painting given to him by his friend Isaiah. He said: “I like to watch that picture. It brings back all the good memories.” (Source: Richard Charan, Sunday Express, September 21, 2023)

0 Comments

Leave a Reply. |

T&T news blogThe intent of this blog is to bring some news from home and other fun items. If you enjoy what you read, please leave us a comment.. Archives

May 2025

Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed