|

Angelo Bissessarsingh

South of San Fernando, in a belt of rolling country bordering on the Oropouche Lagoon mangrove swamps was the district of South Naparima. Around 1810-20, two large sugar plantations–Wellington and Woodland–were established on these lands. The soil was exceedingly rich and those fortunate enough to have properties here, reaped rich annual harvests as LAA DeVerteuil recounted in 1857."Not only do the canes ratoon in this soil for many years, but it does not seem to be favourable to the growth of rank weeds; from three to four annual weedings only are required to keep the cane-fields clean and in good condition. The canes generally do not grow to a very large size; but from 20 to 30 shoots from the same." Initially tilled by slave labour, the estates of South Naparima struggled after Emancipation until the introduction of indentured workers from India who began arriving sporadically in 1845 and in earnest after 1849. From 1860-66 and ending around 1880, an incentive of �5 in lieu of a return passage to India was offered in order to encourage the Indians to settle and create a peasant class.Around 1875-80 a number of labourers whose contracts had expired, began to farm the land assiduously, producing prodigious quantities of rice, ground provisions, vegetables and watermelons. Much of this food found a ready market some four miles away in San Fernando. In time, the village they founded became known as Cooliewood. Dire need for a South road Another smaller hamlet began to sprout downhill to the east around 1900, even closer to the borders of Wellington Estate.This was the birth of Debe, although it was then considered amalgamated to Cooliewood. There were no public services in the area and the villages were almost entirely composed of Indo-Trinidadian agrarian peasants.Owing to the quantity of food being produced here, as well as in Penal some five miles south (which had begun as a settlement in much the same fashion around 1900), there was a dire need for a proper road to get the crops to market. To this call, the wealthy planter and owner of Palmiste Estate, Sir Norman Lamont, lent his voice, and in 1912 he announced:"Towards one other matter I have also been able to make some progress, though I am not able to state definitely that the work will be undertaken. I refer to the possibility of our having a direct road from San Fernando to the south, which would run through Palmiste and Canaan by means of a bridge near the mouth of the river Cipero."His Excellency the Governor himself came to see the proposed route, and the matter is now under his consideration. If the road is made, it will, in my opinion, be of great value to all the people on this estate, as giving them a short and direct road to San Fernando for their marketing." A train trackthrough the swamp This road was not commenced until 1915 and eventually became the San Fernando–Siparia Erin Road. This was not to say, however, that Debe was bereft of transport. In 1912 the Trinidad Government Railway (TGR) extended a line towards the settlement in an infrastructure expansion drive to reach Siparia which happened in 1914. A station was put up at Wellington Road with a crossing gate cutting off traffic on the SS Erin Road when the train was moving across.The project of extending a line through the swamps of Debe was considered to be one of the great engineering feats of the TGR since a massive embankment had to be constructed all the way to Penal. Bits of this earthwork and an old bailey bridge are still visible off Suchit Trace. Debe had a Presbyterian church and school since the 1920s which were on a steep incline just south of the village. Owing to severe earth movements, the old school was abandoned and a new building erected a short distance away in the 1990s. Famous for doubles, aloo pies As early as the 1950s, the Wellington Road junction of Debe was becoming famous as a spot for Indian delicacies, particularly doubles and aloo pies. From the 1940s until it closed in the late 1990s, Hummingbird Cinema operated near this place, showing Indian pictures as its staple fare. In 1962 Dr Eric Williams mandated that the name of the original settlement, Cooliewood, should be changed to Gandhi Village, both to honour the most famous Indian statesman in history and to erase the derogatory nature of the name.Today Debe is a bustling commercial area, very different from its humble origins.Source: Trinidad Guardian, March 18, 2021

0 Comments

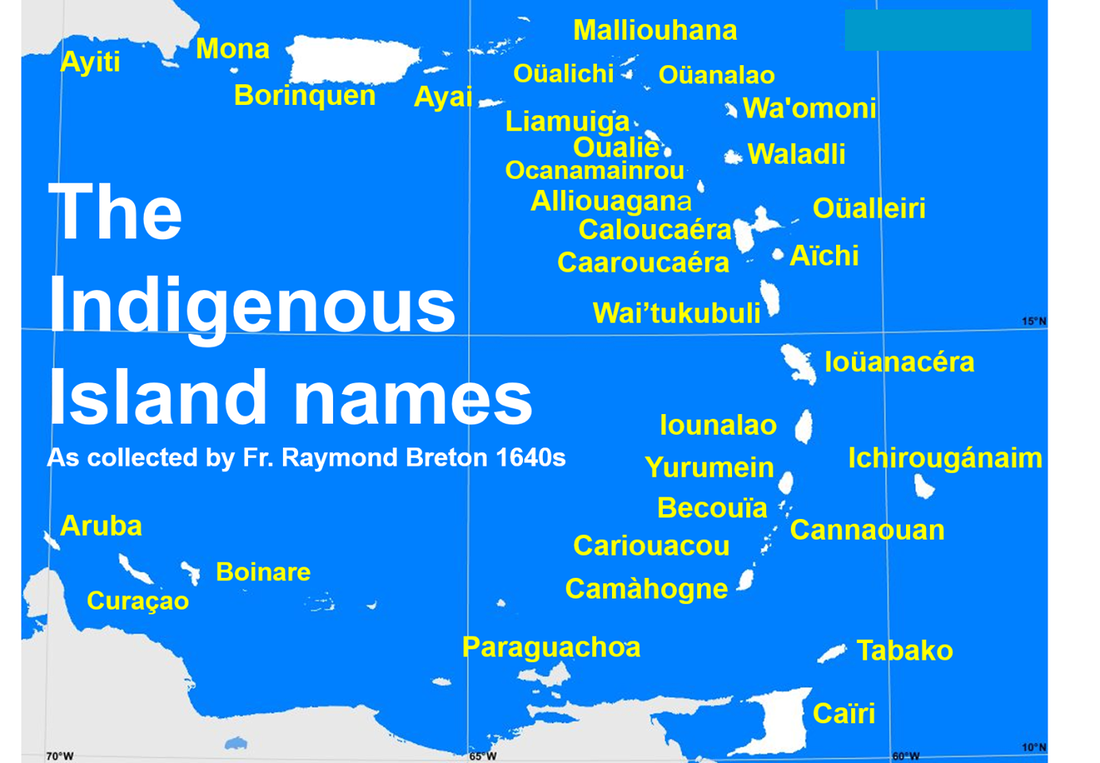

THE INDIGENOUS ISLAND NAMES

From the time of the earliest human settlement of the islands that became known as the Lesser Antilles or the Eastern Caribbean, indigenous adventurers coming from the Orinoco region of South America, were giving names to the islands that they discovered. Most of these names related to the natural resources, wildlife, or type of landscapes that they found on these islands. When Columbus and later arrivals from Europe sailed among the islands for the first time they renamed them without even asking about the original names. Consumed with the myths of late Medieval Christianity, they imposed religious names of Christiandom upon these islands, most of which are the official names still used today. In the 1640s, a French missionary, Fr. Raymond Breton, settled for some years in Guadeloupe and Dominica. He travelled among the islands asking the indigenous Kalinago people what their names of the islands were. On this map we use the names that Fr. Breton collected, although since the 1500s other Europeans had also been collecting names and there is a confusion depending on the sources used. Breton, for instance, is told that Trinidad is Chaleibe, but Walter Raleigh, some fifty years before says it is Caire, which he acknowledges. Smaller, less visited islands such as Bequia, Cannouan, Carriacou, Aruba, Bonaire and Curacao, kept more or less the pronunciation of their original names. The spelling has also changed over the centuries: What Breton records for Dominica as Ouaitoucoubouli, is now more phonetically written as Wai'tukubuli. St. Lucia, Iounalao, has become, Hewanorra. The meanings of the names is also much debated. But whatever the differences, it gives us a taste of what this indigenous island world was like when there was total freedom of movement and trade and interaction, from the mainland up the islands and beyond. Source: Waitukubuli Virtual Museum, March 4, 2021 WHO IS ASA WRIGHT? Together with her husband Newcome Wright, Asa came to Trinidad to settle at Springhill in 1946. Born in Iceland in 1892, Asa was left to carry on the estate when Newcome died in 1955. Friends who enjoyed the flora and fauna of the Arima valley would spend time at Asa's home, hanging out on the large verandah. With the encouragement of her friends, Don and Ginny Eckelberry and Jonnie Fisk, Asa agreed to deed the Springhill estate as a nature centre. Her neighbour in Verdant Vale was William Beebe; his tropical research station at Simla was later added to the lands of the nature centre. The Asa Wright Nature Centre was established in 1967. Asa died in 1971 and is buried in Lapeyrouse Cemetery. Source: Asa Wright Centre & Lodge

Born in Tunapuna, Trinidad and Tobago to lower middle-class black parents one generation removed from emancipation, C. L. R. James (1901-1989) was a social theorist, historian, writer, and revolutionary whose maturity roughly corresponds to what Eric Hobsbawn called ‘the short 20th century.’ It was this contextual standpoint of a Caribbean childhood, and later movements to Britain, United States, and West Africa, that shaped his view of the destructive complexity of the modern world and the imperative to break with “old bourgeois civilization” (James cited by Grimshaw, 1991) In the Global North James is primarily known for two books, The Black Jacobins (1938) which arguably founded Atlantic Studies, and Beyond A Boundary (1963) which influenced the research agenda of late 20th century cultural studies. Each book is indicative of the various wings of James’ wider intellectual project, with the first asking scholars to reconsider the role of racial oppression in capitalism and the second prompting a reconsideration of the role of class formation in popular culture via his treatment of sport, race, and imperialism. These projects combine to provide a Marxist inspired analysis of modernity in which questions of combined and uneven development are foregrounded. The result is to demonstrate the enduring links between advanced capitalist countries and colonized regions along the lines of race, class, and everyday experience. James’ critique of modernity brought worldwide recognition and broke ground for others to work in this field. But equally important are his thoughts on Caribbean politics and economics, topics of his that receive relatively less attention overall. To begin, through The Life of Captain Cipriani (1932) and The Case for West Indian Self-Government (1932), in the pre-war era he shaped the movements for West Indian independence. (Portions of his archive are preserved at Cipriani College of Labour & Co-Operative Studies in Trinidad and Tobago and still maintained by the local labor movement.) On returning to Trinidad in 1956 after being deported from the United States, James became the editor of The Nation, a local newspaper, famously advocating for Frank Worrell to become captain of the West Indies Cricket Team. This well-known case is but one minor example of how James used the position to revisit fundamental questions about government and society, sensing the significance of the historical moment where West Indians could become the vanguard in the struggle for more egalitarian social relations. In the post-independence period James took stock of the various contradictions, competitions, and antagonisms that circulated in the social life in the West Indies and suggested that efforts to induce modernization were shortsighted. This put him in conflict with the post-independence political class, whose budding radicalism was tempered and redirected into cultural nationalism. For example, contra the views of notable Caribbean political economists like Sir Arthur Lewis who thought that Caribbean development was hampered by unemployment and a weak local capitalist class, James stressed how prosperity could be achieved through labor taking a greater control of production. Effectively, moving Caribbean societies from an agricultural base to industrialism would likely prove difficult unless there was greater attention to the legacies of colonial governance created by racial capitalism. In summary, for James emancipation can best be achieved through a social reconstruction of the way people relate to one another. Much needed if one were to escape the “problems of nationality.” Sadly, James’ views did not prevail. Escaping the problems of nationality led James’ to have a significant role in promoting Pan-Africanism, a topic he wrote about in Nkrumah and the Ghana Revolution (1977). Later when reflecting back on this period, he wrote that, “there were never all told more than a dozen of us, who banded ourselves together in 1935 to propagate and organize for the emancipation of Africa. For years, we seemed, to the official and the learned world, to be at best, political illiterates. Yet we were part of the New World pregnant in their old decay.” (James, Tomorrow and Today, 1) These words capture so well the many diverse elements of James’ work, like his Marxist reading of history and his contribution of early post-colonial thought rubbed up against the incredulity of the European intellectual class. A committed, practising post-Trotskyist, James’ politics catered towards revolutionary emancipatory impulses, and suggested that gradual improvements of living and working conditions were insufficient. Rather, his politics centred upon the historical and geographic inter-connectedness between societies and the people who live in them. In this respect, James anticipated the value of methodologies that examine the transnational movement of capital and knowledge, goods and people. James’ contribution to cultural studies in the UK, while significant was comparatively slow to develop. Despite being known in niche academics circles, it was only in the mid-1980s and early 1990s that his scholarly status began to increase through Stuart Hall, Bill Schwarz, and other theorists in the postcolonial turn. Three years before his death, a BBC Arena documentary, C. L. R. James’ First Cricket XI helped cement this recognition. Even so, Jonathan Scott (2018) has recently warned how this canonization courts a misinterpretation where James’ project is framed as “primarily concerned with self-fashioning and cultural identity,” an interpretation clearly at odds with James emphasis on the totality of political life and its historical dimensions. Granted, James’ wide and deep range is hard to capture in a few paragraphs, but there is an analytical urgency to his project, to grasp the whole to ultimately offer a critique of, and remedy to, the partiality of capitalist ideology, while also resisting the established dogmas of mainstream Marxism. Each year more of James’ work is put in circulation increasing the opportunities for sociologists to engage with all of his writing. The most promising of these comes from his time in America, the creation of and iterations from ‘Johnson-Forest’ Tendency particularly how it created a scaffolding for the interpretive analysis in his later work (see Grimshaw 1991). I suspect James’ importance and contribution to the development of global social theory will only increase in the coming decades. Perhaps aptly so given that more than 80 years after the publication of The Black Jacobins, he remains a companion able to help students and scholars “pioneer into regions Caesar never knew” (2005, 1). Essential Reading: James, C. L. R. 2005 [1963]. Beyond A Boundary. Yellow Jersey Press, London. James, C. L. R. 1989 [1963]. The Black Jacobins. Vintage, New York. [First published in 1938] James, C. L. R. (nd) Tomorrow and Today: A Vision, New World Journal Further Reading: Grimshaw, Anna, 1991. C.L.R. James: A Revolutionary Vision for the 20th Century Henry, Paget, and Buhle, Paul (eds) 1992. C. L. R. James’s Caribbean, Duke University Press, Durham James, C. L. R. 1992. The C. L. R. James Reader (edited by Anna Grimshaw) Wiley Blackwell, Oxford. Robinson, Cedric 1983. Black Marxism: The Making of the Black Radical Tradition, The University of North Carolina Press, Chapel Hill. Chapter 10 Scott, Jonathan. 2018. The Americanisation of C. L. R. James, Race & Class 60(2) Laura Roberts-Nkrumah grew up in St. James, Trinidad and Tobago, a community rich with plant life.

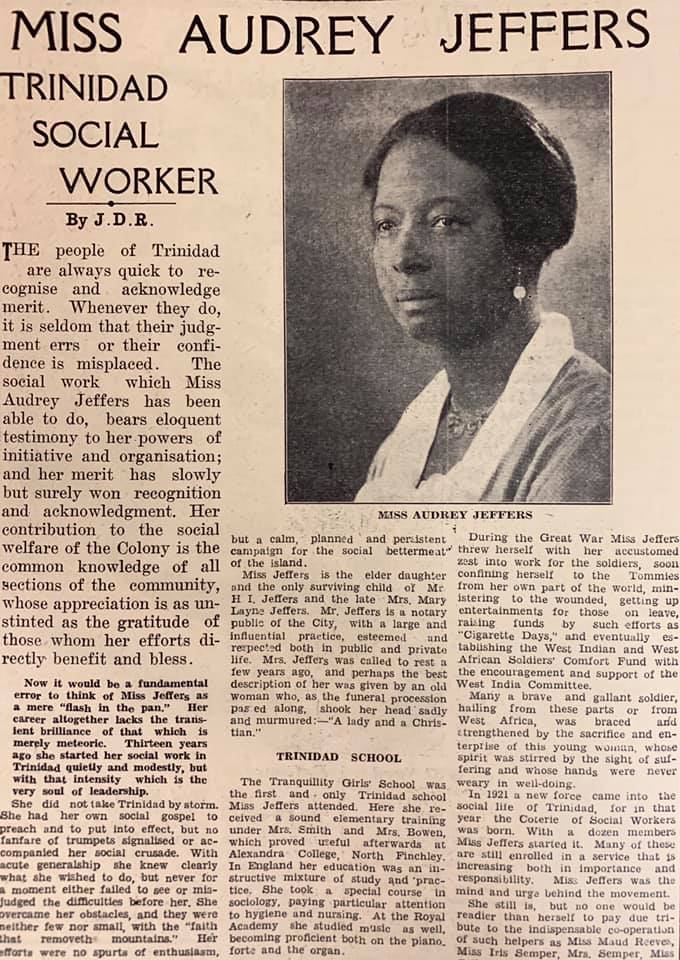

“There were many fruit trees,” she says. It was this proximity to nature’s bounty that fostered her early attraction to flora and food, an interest that would eventually lead to her outstanding career as a scientist, agriculturalist, educator and Caribbean pioneer in the study and cultivation of breadfruit. Professor Roberts-Nkrumah is Professor of Crop Science and Production within the Department of Food Production at UWI St Augustine’s Faculty of Food and Agriculture (FFA). During her more than 30-year career she has trained many students in the science and production of various crops. “My primary career goal as a member of academic staff, and former student of this faculty, was to make a difference, in at least in some small way, to the food and agriculture sector in the Caribbean. I have shared this goal with my students; their training at the FFA was about much more than certification; it was about capacity building for the development of our countries and region”, she says. Professor Roberts-Nkrumah is most well-known for her work in breadfruit. She has raised the stature of this neglected and underutilised crop, which was traditionally important for food security in the Caribbean but stigmatised as ‘slave food’ and largely ignored by research. Her work includes expanding the range of cultivars (different varieties) in the region through importation, and establishing a germplasm collection at UWI St. Augustine Campus. The collection has been evaluated for growth, development, seasonality, yield, disease resistance, nutritional content and, more recently, there has been DNA characterisation. Studies have been conducted on propagation, orchard management, as well as on consumer acceptance, contribution to food security and farm income. “Most persons are unaware that there are different types of breadfruit. This collection is an educational and research resource that is critical if the commercial potential of breadfruit for human nutrition, and for other methods of utilization, for example, medicine is to developed beyond its current level in T&T and the wider Caribbean”. Based on her work in breadfruit, Professor Roberts-Nkrumah was commissioned to prepare a strategic plan for the development of a breadfruit and breadnut industry in St Kitts and Nevis. She initiated, secured external funding for, and co-convened the first International Breadfruit Conference, which was held in Trinidad and Tobago in 2015. She was also invited to contributeto a review chapter on breadfruit production for the prestigious publication, Horticultural Reviews. “A number of new breadfruit products, as diverse as chips, wines and beauty products are already being produced on a commercial scale elsewhere. My greatest satisfaction would be the emergence of a sustainable breadfruit industry in the region based on innovative products, which is entirely possible with our people’s creativity. Support for multi-disciplinary research and consumer education will be two key requirements” Apart from her work in this area, Professor Roberts-Nkrumah is a pioneering woman in science, who for many years has operated at the highest level of her field. Data from UNESCO’s Institute for Statistics shows that less than 30 percent of the world’s researchers are women, and only around 30 percent of all female students select STEM-related fields in higher education. Recognising the importance of women in the sciences, the UN General Assembly made February 11 the annual International Day of Women and Girls in Science. Professor Roberts-Nkrumah says many women inspired her own journey into the sciences, starting with her grandmother: “She was recognised as a champion farmer in Tobago. My grandmother was an independent and strong woman who continued to farm even in her 70’s. I have fond memories of the delicious fruits, cocoa tea, and high quality cassava, sweet potatoes and pigeon peas that she grew and our family enjoyed.” She admires scientists such as Professor Margaret Sedley, a botanist, whose work was closely linked with the development of the avocado industry in Australia and Professor Ruth Oniang’o, a pioneer in food science and nutrition studies on indigenous crops in Kenya. She was most inspired in her career, however, by Professor Lawrence Wilson, a leader in research on tropical root crops at The UWI, who taught her at both undergraduate and graduate levels. “I admired his insight and creativity as a scientist,” she says. “He instilled in me the significance of basic scientific knowledge for understanding crop physiology and addressing crop production issues.” Professor Roberts-Nkrumah’s legacy of work also includes outreach activities with crop producers and nurseries, and the general public throughout the Caribbean. Apart from providing hands-on training, several manuals and fact sheets have been made available, including manuals on breadfruit propagation and orchard management, which were commissioned by the Food and Agriculture Organisation and are available online. Her work has produced 117 publications, among which is a book titled The Breadfruit Germplasm Collection at the University of the West Indies, St Augustine Campus, a reference text for stakeholders in the breadfruit sector, from scientists, to growers, sellers and consumers. When asked about her career success, she credits her family life: “I consider myself to have been blessed by my family background, which provided stability, focus, a high value on education, strong work ethic and strong Christian values. All of these and the commitment to service were reinforced at school.” As a wife, mother, and daughter, she has had to balance work with family life and responsibilities. This was not always a simple matter but unconditional support from her husband and children helped to make it possible. “They have accompanied me in the field on many occasions,” she says. “As much as possible I limited my travelling for field research in the Caribbean to the school vacation period, when the family could also travel with me. This has paid dividends as I now see the children’s own gardening initiatives and hear them offering ‘on target’ advice to their peers.” Even though she is a scientist, as a young student Professor Roberts-Nkrumah loved English Literature as well. However, her desire for the outdoors pushed her towards science and agriculture. And though she has experienced numerous challenges during her career -- from the very limited scientific literature on breadfruit, to the difficulties of data collection in the field, to having to balance research with her heavy teaching load -- her work has revolutionised the breadfruit sector and has the potential to make a major impact on regional food security. Perhaps more importantly, she followed her passion, found her mission and built a career. “The application of science to food and agriculture is a most worthwhile endeavor. It’s about knowing what you were born to do. Focus, faith and willingness to work for the benefit of others, even with obstacles, will always be rewarding – “Non sine pulvere palmam” (Not without the dust the victory). Source: UWI Campus News, Feb 15, 2021 We’re recognizing the contributions of Audrey Jeffers, the first woman to be elected to the Port of Spain Municipal Council and the first woman to sit on the Legislative Council of Trinidad and Tobago. Born on February 12th 1898 in Trinidad, Audrey Layne Jeffers was a prominent social worker and an activist. As a young girl, she attended the Tranquility Girls’ School in Port of Spain, and continued her studies in social science abroad. During World War I, she treated soldiers from the Caribbean and West Africa, eventually establishing an organization called the West Indian and West African Soldiers’ Comfort Fund to continue these efforts. In April 1921, she became one of the founding members of the Coterie of Social Workers, which provided social services in Trinidad. With the Coterie, Jeffers played a major role in the institution of several free breakfast sheds, including the Children’s Breakfast Centre in Port of Spain. Jeffers also helped to establish the St. Mary’s Home for the Blind (which was named after her mother, Ms. Mary Jeffers), as well as the Maud Reeves Hostel for Working Girls. In 1929, Jeffers represented Trinidad and Tobago at the International Council for Women in London, where she was one of two representatives of colour. Upon her return to Trinidad, she opened the Workingmen’s Dining Shed in South Quay. In October 1936, she became the first woman to be elected to the Port of Spain Municipal Council and in 1946, the first woman to sit on the Legislative Council of Trinidad and Tobago. Jeffers also sat on the Franchise Committee in 1945, where she shocked many by voting against universal adult suffrage (the right to vote). Her lack of support in this moment has been described as a misstep in her career. It did not, however, prevent universal adult suffrage from being instituted in Trinidad and Tobago in 1945. Jeffers received the MBE (Member of the Order of the British Empire) in 1921 and the OBE (Officer of the Order of the British Empire) in 1959 for her contributions to social services in Trinidad and Tobago. In 1958, she was appointed the honourary Consul for the Republic of Liberia. She passed away on June 24, 1968 and was posthumously awarded the Chaconia Gold Medal for Social Service at Trinidad and Tobago’s first Independence Day Award Ceremony in 1969. The Audrey Jeffers Highway, which runs from Port of Spain to Cocorite, and the Audrey Jeffers School for the Deaf in San Fernando, were both named in her honour. This photo of Audrey Jeffers and the corresponding article, “Miss Audrey Jeffers: Trinidad Social Worker'' by J. D. R. are both courtesy of the Trinidad Guardian, published on September 2nd 1934. This newspaper is part of the NATT Newspaper Collection. References: Khan, Nasser. Profiles, Heroes, Role Models and Pioneers of Trinidad and Tobago: Celebrating Our 50 Years of Independence 1962-2012. First Citizens Bank, 2012. Lopez, Suzanne, and Rhona Baptiste. The 90 Most Prominent Women in Trinidad and Tobago. Trinidad Express Newspapers, 1991. Source: National Archives of Trinidad and Tobago, February 17,2021

Yesterday I saw some beautiful hammocks on sale at the Blind Welfare Institute Outlet Store on Coffee Street , San Fernando. Did you know that the hammock is in fact a legacy of the first people who found them to be easy beds when moving from place to place. They were skilled at weaving cotton to make hammocks.The word “hammock” was derived from the Taino hamaca or yamaca, and the first hammocks are thought to have been woven out of tree bark. According to source cited below the hammock was lightweight and easy to set up . It was safer than sleeping on the floor, where one could be vulnerable to snakes and other crawling creatures. It was also quite versatile since it could be used as a bed, chair, a sack, or a fishing net. Today hammocks are still used by farmers like this group in their makeshift camp in the forests of Quinam. In my travels I also noticed hammocks being used by Indigenous Kogi Tribes in Columbia. Some people use them as a place for relaxation , somewhere you could take a short snooze. Source: Patricia Bissessar, Virtual Museum of TT, January 2021

A rebel Trinidadian, who never learnt to speak Chinese fluently, never even liked Chinese food eventually became the Foreign Minister of China, after establishing himself as the backbone of the government of Sun Yat-Sen, the first president and founding father of the Republic of China.

Eugene Chen, the ultimate Trinidadian was born in San Fernando in 1876, of mixed heritage that included Chinese, African and Spanish. The St Mary's College graduate became the first lawyer of Chinese descent in the Caribbean having studied in London, after which he returned home to marry a black woman, Agatha Alphonsin Ganteaume, against his parents’ wishes. But in 1912, Chen left Trinidad aiming to join the Chinese Nationalist Movement, headed by Sun Yat-Sen. Once in China, he started the Peking Gazette, writing articles against the British colonial powers, in English. Five years later he fearlessly published an article revealing secret negotiations between the then Premier of China, warlord Duan Qirui and the Japanese, which landed him in jail. This got the attention of Sun Yat-Sen and four months later, a free man, Eugene left Beijing and went to join Sun in Shanghai, where he established the Shanghai Gazette and became Sun’s confidante and legal advisor. He led a boycott against the British interest in China, causing Britain to back down and to sign the Chen-O’Malley Agreement in February 1927 which paved the way for Hong Kong to be returned to China 70 years later. Eugene Chen never returned to Trinidad but died in 1944 branded as one of the most important Chinese diplomats of the 1920s. In a 1931 publication on China, Time Magazine called Eugene Chen “the brains, the master propagandist of China and a fearless editor in his own right”. -Leah Skeete Source: Virtual Museum of TT, Dec. 28, 2020 John and Sarah Morton arrived in Trinidad in 1868 to start their mission to indentured Indians. (The Presbyterian Church in Canada Archives [G-93-FC-2]) In 1864, a Presbyterian minister from Nova Scotia arrived in Trinidad and changed the face of education on the island forever. But historians say his legacy isn't entirely positive. Rev. John Morton was born to Scottish parents in Stellarton, N.S., then called Albion Mines, in 1839. He went on to study at the Free Church College in Halifax and was licensed and ordained to serve in Bridgewater, N.S., in 1861. According to Rev. Peter Bush, editor of the Presbyterian Church in Canada's newsletter, Presbyterian History, in the winter of 1864 Morton left Nova Scotia for the Caribbean. "He had, we think, diphtheria and for health reasons had traveled to Trinidad because his doctor ordered that he do that," Bush said in an interview. The ship he sailed on was carrying salted fish and lumber — part of a thriving two-way trade between the British West Indies and Nova Scotia that had been happening since the 1700s. While in Trinidad, Morton saw the condition of indentured Indians who had been brought from India to the island by the British, starting in 1845, to fill in the labour gap left by the abolition of slavery. "He saw that the indentured Indian workers were not being served, not being cared for by any Christian group, that there were Presbyterians who were working with the Black community in Trinidad and with the Indigenous people of Trinidad. But no one was working with the indentured Indian workers," Bush said. Ignored, alienated and ostracizedBetween 1845 and 1917 over 140,000 Indians were transported to Trinidad to work on the island's sugar and cocoa estates. Most never returned to India. Jerome Teelucksingh, a descendant of indentured Indians and lecturer in history at the University of the West Indies at St. Augustine, said Morton would have found these labourers living in wretched conditions and shunned by the rest of Trinidad society. "They would have been ignored, they'd have been alienated, ostracized, the majority were poverty stricken," he said. "And remember at that time the planters and the colonial-era British government were focused only on obtaining their labour so they were not concerned about their health, welfare or their culture. It was a state that was really despicable." Convinced that he had to aid this growing community, Morton tried to enlist the help of Presbyterians in the United States and the Church of Scotland, but to no avail. He returned home and found a receptive audience in Nova Scotia's Presbyterian community. The Presbyterian Church in Nova Scotia was already familiar with foreign mission work, as Rev. John Geddie had been dispatched from Pictou, N.S., to the New Hebrides (now Vanuatu) in the South Pacific in 1846. Morton's request for a mission was approved and, after raising funds for a year, he set off for Trinidad with his wife, Sarah, and his daughter Agnes — arriving in the capital, Port-of-Spain, on Jan. 3, 1868. He set up a mission base and home in Iere Village in the south of the island but eventually moved his home to the southern town of San Fernando. From the outset, Morton saw education as essential to his mission, according to Brinsley Samaroo, professor emeritus of history at the University of the West Indies at St. Augustine. "Most of these missionaries were Scottish Canadians, their ancestors had come from Scotland," he said. "The Scots have always been very, very much concerned about education. And ... whereas Morton was more concerned about evangelization, he used education as a tool towards that." The indentured Indians in Trinidad had always been reluctant to enrol their children, and especially their daughters, in the Roman Catholic, Anglican or ward schools that served the white and African-Trinidadian populations. At the time, Teelucksingh said, Indian children were despised and treated with contempt because of their dress, food, religion and culture. Schools also conducted classes exclusively in English, which most of the new immigrants could not speak. Canadian Mission Indian schoolsRealizing the daunting extent of his planned undertaking, Morton appealed to the church board in Nova Scotia for help and by 1870 he was joined by Rev. Kenneth James Grant from Merigomish, N.S. They established a number of Canadian Mission Indian schools, which later became known simply as Canadian Mission schools. Unlike other religious groups on the island, Morton and Grant opted to teach in the language of the indentured workers. They initially imported Hindi and Urdu religious and teaching books from missions in India but eventually set up their own printing press locally. By speaking their language and incorporating it into church services, classes and even the names of their churches, the efforts of the missionaries were embraced by the indentured labourers. "All of that really appealed to the Indians because you were meeting them on their own ground and very slowly and subtly moving them away from that ground and onto a Christian ground," said Samaroo. "But I think the most important thing is that they all understood that once they got a Western education via the missionaries, that was the beginning of the end of their life on the plantation." The missionaries also provided material benefits to the Indian population, including food and medicines imported from Canada, according to Teelucksingh. A few other male and female missionaries from the Maritimes went to Trinidad over the years, but the focus was always on training local converts to keep up with the tremendous demand for schools. A Presbyterian theological college was established in 1892 and by 1894 a teachers' training college was opened. As a historian of the Presbyterian Church in Canada, Bush said he is fascinated by the fact the "mission in Trinidad is led largely by the Indian community." "If you look at our records ... in Canada, our records record the names of teachers and lay missionaries, long lists of Indian names who are listed in our books as being members of the mission, the Presbyterian Church in Canada, in Trinidad." A plaque outside the Morton Memorial Presbyterian Church in Guaico, Trinidad, pays tribute to the work of Morton. (Susan Baboolal-Sam/National Trust of Trinidad & Tobago) Teelucksingh said in addition to opening numerous schools in areas with a high concentration of indentured Indians, the Canadian Mission also offered night classes for adults and women missionaries from Canada taught women "catechism and domestic chores." The popularity of the education opportunities offered by the Nova Scotian missionaries and their use of locally trained teachers led to a rapid expansion of their mission. Although conversion was not a requirement for taking part in their educational programs, it was a requirement for taking up teaching positions, and some Indians, though not the majority, converted for the opportunities it offered for upward mobility. Samaroo estimated that by 1956 there were 71 Presbyterian elementary and secondary schools in Trinidad serving 3,000 students. Unintended consequencesHe said that the influence of the missions also caused unintended negative effects on the Indian community, and the island in general, that persist to this day. According to Samaroo, Presbyterian Indians became alienated from their culture as they were taught that they shouldn't bother with their old cultural ways. He said because their education allowed them to prosper and move away from the plantations, it allowed them to ascend into "a higher echelon of the society" and become an "elite Indian class." The Morton Memorial Presbyterian Church is still in use. (Susan Baboolal-Sam/National Trust of Trinidad & Tobago) Teelucksingh said this distinction lessened when Hindu and Muslim schools started to be established in the 20th century, allowing the rest of the Indian population to catch up.

He said it became evident that many converts were actually "temporary Presbyterians," as they went to teach at the new schools with many reverting to their previous religious practices. The more problematic side-effect, according to Samaroo, was that the Canadian Mission deepened racial divisions on the island. He said the creation of divisions was not deliberate or unique to the missionaries but part of the British colonial system of "divide and rule." "By going to the Indians and speaking in Indian languages and calling churches after Indian names," Samaroo said, "it created antagonism because you didn't have too many Black people in the Presbyterian circle, very few of them ... and that created a kind of ethnic competition, a kind of ethnic antagonism." Despite the creation of divisions within the Indian community and the wider community, Samaroo believes the Canadian Mission had an overwhelmingly positive effect on the island. "I think they were the major agencies for the emancipation of the Indians from the plantations to the professions," he said. "And had they not come, I think it would have taken much longer for the Indians to escape the drudgery of the plantation." Today, four of the most prestigious high schools in Trinidad & Tobago — Naparima College, Naparima Girls' High School, Hillview College and St. Augustine Girls' High School — can trace their roots directly back to the work of missionaries from Nova Scotia. Source: Vernon Ramesar · CBC News · Dec 28, 2020 |

T&T news blogThe intent of this blog is to bring some news from home and other fun items. If you enjoy what you read, please leave us a comment.. Archives

June 2025

Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed